This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Symbols Over Substance: An Analysis of the Freeman-Mead Controversy

by Rae Goodell

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 15, No. 5 September-October 1983, p. 27 — 29

Rae Goodell teaches in the writing program at MIT.

Last winter Margaret Mead, who during her lifetime had been an eminent anthropologist and a favorite with the media, took an astonishing drubbing from the press. The ironies of this particular incident offer some important insights into the media’s coverage of science-related material.

On January 31, 1983, The New York Times announced on page one that Margaret Mead’s best-selling Coming of Age in Samoa had been seriously challenged in a new book by Australian anthropologist Derek Freeman, Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth. According to the Times, the new book contended that Mead’s inexperience, her failure to live with the Samoans, and particularly her political biases rendered her conclusions about Samoa largely invalid, a “wholesale self-deception” on a scale unprecedented in the history of the behavioral sciences. In contrast to Mead, the New York Times reported, Freeman found the Samoans to be a competitive, violent, jealous people among whom adolescence was stressful and sex repressed. The book, which was soon to be published by Harvard University Press, raised important questions, according to the New York Times, not only about Mead’s work, but also about the role of nature and nurture in human behavior and about the integrity of scholarship in the behavioral sciences.

Offering celebrity, controversy, color, and credibility, the story spread quickly, sometimes appearing in a half dozen forms in the same newspaper — the New York Times for one — first as news, then perhaps a followup, an interview with Freeman, an editorial, coverage of a scientific seminar, a feature on Samoa, or a book review. Headlines scattered across newstands read “Sex and Violence in Samoa,” (Life, May 1983), “Bursting the South Sea Bubble,” (Time, 2/14/83), “Shooting Down Mead’s Classic Myths,” (Boston Globe, 3/11/83), and “Trouble in Paradise” (New Republic, 3/28/83).

From the beginning, Freeman was usually given the benefit of the doubt. The original New York Times story, calling him “Professor Freeman” and Mead “Miss Mead,” devoted approximately three of its 40 paragraphs to pallid defense of Mead from her colleagues. The coverage settled comfortably into a mold that depicted Freeman as a conscientious scientific expert who had produced a scholarly, meticulous study that exposed serious problems in the work of a romantic, inexperienced Margaret Mead.

Expanding on Freeman’s attack on Mead, the press had a heyday. Time‘s story began: “On Aug. 31, 1925, with romantic South Sea tales of Robert Louis Stevenson filling her head, Margaret Mead, 23, stood at the rail of a Matson liner steaming into the lush port of Pago Pago, Samoa.” (2/14/83, p. 68) Discover, after dredging up the old backbiting gossip that circulated while Mead was alive — for example, a Florida governor called her a “dirty old lady” for advocating legalization of marijuana — avowed that “Mead was very young when she first decided to visit Samoa, and very inexperienced. Twenty-three years old and deeply influenced by Franz Boas . . . she badly wanted to impress her mentor . . . After nine months of watching, asking, nosing about, eating fish and tropical fruit with her fingers, and dressing in the local garb, she felt that she had enough material to present her conclusions to Boas.” (April 1983, p. 28)

Even the illustrations in magazine articles tended to underscore the juxtaposition of the level-headed Freeman and the fluffy-headed Mead. Discover featured sketches of a young Mead taking notes as Samoan youngsters gossiped and kissed, also reclining in a Samoan canoe, and getting instructions from Boas. Freeman, on the other hand, sits contemplatively at his typewriter.

How could Margaret Mead’s stock with the press have fallen so far so fast? For one thing, reporters had always been ambivalent about their frequent and favorable coverage of Mead. There is a feeling among reporters as well as scientists that there is something a little unseemly about a scientist who welcomes popular attention. Such a scientist is assumed to have sold out in some sense, and to have sacrificed his or her ability to be a good scientist. If Freeman had been attacking a less celebrated scientist — say, Ruth Benedict — it is hard to imagine that he would not have been greeted more skeptically. Besides, the press wanted to believe; the downfall of a popular hero makes a great story.

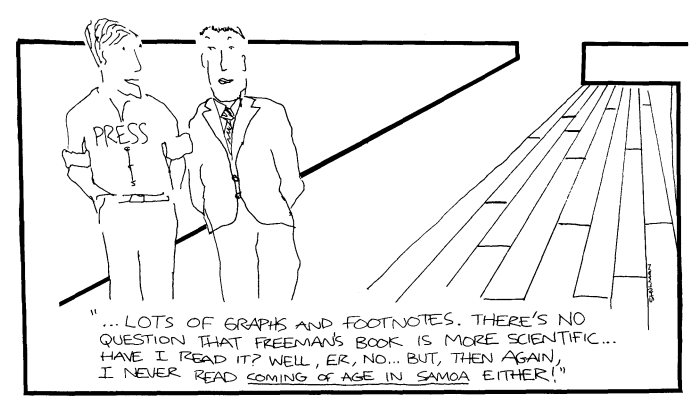

Freeman had a second advantage: both he and his book had an air of scientific respectability. Freeman presented himself in interviews as patient, objective, methodical, and — let’s face it — male. “He seems much more the scientist,” explained Discover. Much was also made of the scholarly appearance of Freeman’s book, such as its graphs and tables and, as the Times noted, “55 pages of notes.” Continues Discover, “. . . his book seems completely and thoroughly documented [and to] . . . convincingly debunk many of Mead’s observations.” As the Boston Globe put it, “While Mead wrote rhapsodically of an Eden-like Samoa of brown-skinned natives enjoying free sex under the palm trees untouched by war and jealousy and neurosis, Freeman carefully documents his assertion that Samoan culture is intensely competitive.” (3/11/83, p. 36) It also impressed the press that Freeman had immersed himself in Samoan culture, receiving an honorary title as an adopted son of a chief, while Mead had lived in quarters attached to the home of an American family.

In short, Freeman offered the press more of the superficial trappings of science, from footnotes to honorary native titles, and much of the press fell for the illusion.

And illusion it was, as became apparent as reviews began to appear from anthropologists close to the field. Writing in New Republic, George Washington University anthropologist Colin Turnbull pointed out that, for Mead’s study of female adolescence her choice of quarters removed from a Samoan home was sound, offering her more privacy and more freedom of movement than she would have had as a female in a Samoan home. New York University head of anthropology Annette Weiner adds that an honorary “chief” would be as limited in his access to the more domestic aspects of Samoan life as Mead was to the more male-dominated governmental aspects. Separated in space, time, and gender, they saw different parts of Samoa. Furthermore, noted Ward Goodenough of University of Hawaii at Manoa in a letter to Science, Mead’s field research has little to do with her current reputation in anthropology. Her major contributions have been in questioning both lay and professional assumptions about human behavior. “That her own empirical research in connection with these questions was of questionable quality and that at times she overstated her case are minor matters compared with the role she played in raising these questions and stimulating others to examine them.” (5/27/83, p. 906)

As for Freeman’s book being a “scholarly refutation,” Weiner notes that in Freeman’s field, the scholarly tradition calls for publishing one’s own monograph on a culture — something Freeman has not done on Samoa — and letting the community of anthropologists judge its implications; a personal, direct attack on a colleague is virtually unprecedented. The book’s documentation, reviewers have found — as they do for all scientific discourse — contains bias, conjecture, distortion, and selective use of data, in this case often from Mead’s own honest, often humorous, self-searching memoirs and records. I happened to find one error along these lines. I looked up the passage in Freeman’s book that describes her starry-eyed arrival in Samoa, the episode from which Time derived its lead, and found reference to one of Mead’s published letters. Checking out the letter itself, I found no mention of Stevenson or romantic tales whatsoever, and a tone that was downright laconic at times.

Finally, Freeman’s challenge to anthropological theory, reviewers generally agreed, was insignificant. Even if all of his claims about Margaret Mead were correct (and for certain some of them are — her work has been criticized before), his findings offered no theoretical insight. The book is, Rice University anthropology department chair George E. Marcus wrote in The New York Times Book Review, “a work of great mischief.”

The Freeman/Mead affair is not the first time that the press went for symbols rather than substance in science. Press critics note in coverage of scientific controversies a heavy reliance on official or well-established scientific experts. One study contends, for example, that California reporters missed the story on hazards of asbestos in the state because they were checking only with government sources, not labor leaders and others. According to other studies, when official government sources failed to provide a complete and convincing story about Three Mile Island and about swine flu, reporters became indignant — but not investigative. In other words, at times reporters place inappropriate faith in one source or one kind of source of information, rather than seeking out the full range of views that constitute a scientific controversy.

The person who would have had the stature and articulateness to force a more balanced press coverage of the Freeman-Mead incident was missing, of course — Mead herself. As a result, much of the public has likely been left with the impression that she has been exposed as an incompetent scientist. But she still gets the last word. Her colleague Rhoda Metraux points out that in a 1959 article about Franz Boas, Mead wrote, ”The myths that obscure the personality of an intellectual leader gather thickest in the years immediately following his death, when there are many people alive who speak with varyingly authoritative voices, and the next younger generation listens.”

>> Back to Vol. 15, No. 5 <<