This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Book Review: Sexual Preference — Its Development in Men and Women

by Larry Goldsmith

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 14, No. 5 September-October 1982, p. 29 — 31

Larry Goldsmith is a staff reporter for Gay Community News. An earlier version of this review was published in Gay Community News.

Sexual Preference: Its Development in Men and Women by Alan P. Bell, Martin S. Weinberg, and Susan Kiefer Hammersmith, Indiana University Press, Indiana, 2 Volumes, 1981, $40.

It was not until the late nineteenth century that scientists invented the homosexual. That is not to say there were no sexual acts between persons of the same gender prior to that time. But the idea of homosexuals and heterosexuals as two identifiable and mutually exclusive types of human being first surfaced in Germany as a popular reaction to a proposed law forbidding homosexual acts between men. Given this new category of human existence, it remained only for a certain Dr. Benkert, writing in 1869, to coin an appropriate term — homosexuality.

Ever since that time, doctors, lawyers, psychologists, and scientists have given their best efforts to answering the question: Why are there homosexuals? They have poked and probed, interrogated and incarcerated, synthesized and analyzed, castrated and lobotomized — all in an effort to understand the origins of this troublesome “condition.” But, curiously, in that time the question “What is a homosexual?” has only rarely been posed and has never satisfactorily been answered.

In a recent report entitled Sexual Preference: Its Development in Men and Women, researchers at the Alfred C. Kinsey Institute for Sex Research again ask the first question and ignore the second. To test the importance of various childhood experiences in causing homosexuality, Alan P. Bell, Martin S. Weinberg, and Sue Kiefer Hammersmith questioned self-identified homosexuals and heterosexuals and compared the responses of the two groups.

Sexuality Defies Categories

Too many people begin by assuming that there are two types of people in the world: homosexuals and heterosexuals. Of course, not all homosexual behavior is limited to those people we call homosexuals, and not all of those people labeled homosexual behave consistently as homosexuals. We can account for this incongruity by revising our categories in one of two ways. Those who fit clearly into neither category might make up some sort of special case (we might call them bisexual or asexual, for example). Or the conditions under which we observed candidates for classification might be “unfair” (“He was drunk,” “It’s just a phase,” or “That’s a normal outlet in boarding school” might serve to excuse them.)

Rather than face the embarrassment of explaining so many exceptions to our two categories, we might simply increase the number of classifications. We might allot a greater legitimacy to categories such as bisexual, or we might opt, as did the late Dr. Kinsey, for a whole spectrum of sexual orientations (“You’re a 6, but I’m only a 4.”). Yet not even Kinsey’s valiant attempt at quantification can alter the fact that human sexuality, like all human experience, defies quantification, delimitation, or comprehensive objective description. The French philosopher Guy Hocquenghem, in his book Homosexual Desire, characterizes sexuality as a “polyvocal flux of desire.” Desire, for Hocquenghem, cannot be broken into components; any categorization of sexuality as, for instance, “homosexual desire” or “heterosexual desire” is but an “arbitrarily frozen frame” of the flux. In short, because of the complex and ineluctable nature of human sexuality, any attempt at definition will necessarily be incomplete.

Social Control

Our insistence upon forcing sexuality into categories too narrow to accommodate our experience means that we are forever denying aspects of that experience. When we say “He’s not really a homosexual, he was just drunk” (or, “He was just fooling around”) we deny the homosexual component of a person’s sexuality in exactly the same way as when we say “She must be a homosexual — she once had sex with another woman.”

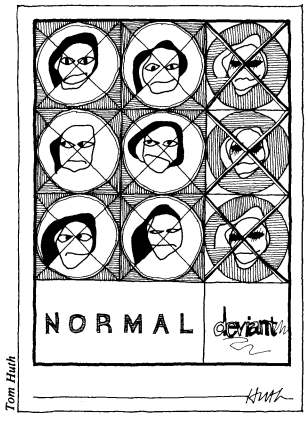

With such deliberate self-deception — through so-called objective description of human experience — science serves as a form of social control. By providing us with the artificial yet well-defined conditions of homosexual and heterosexual, psychologists and sociologists draw a clear line between what is normal and what is deviant. A move in the direction of deviancy means either that a person acted under special circumstances or that the person is a full-fledged deviant. The distinctness of the line which must be crossed is a strong deterrent to the person contemplating the visit into deviancy. And the strict segregation enforced by such thinking not only helps to keep most people “normal,” it serves also to keep the “deviant” fixed in her or his place.1

Scientists and laypersons alike tend to view the study of sexuality as merely an objective rendering of human behavioral patterns. They often fail to recognize that the very identification of a condition — the step that takes us from individual human behavior to pathology — imposes constraints on behavior. Legislation and psychiatric opinion create real limitations on appropriate behavior by adopting standards of criminality and legality or sickness and health. In adopting a teleological approach to the study of homosexuality, the authors of Sexual Preference disingenuously open the door to direct scientific control of individual sexuality.

The Great Debate

Ironically, the view of homosexuality as a pathological condition, either biological or developing in the first few years of childhood, has long been a source of comfort to those who call themselves homosexuals. Dr. Benkert, along with Magnus Hirschfeld and other leaders of the homosexual emancipation movement in Germany, argued that homosexuality could not be prohibited by law because it was merely a matter of individual biology. The Reichstag might just as well move to ban diabetes and epilepsy, too. Freud and his followers later shifted the focus from biology to early childhood experience, blaming the parents of the homosexual for the homosexual’s condition.

The debate over the cause of homosexuality has centered on the question of whether biology or society is to blame. Is Nature at fault? A well-known chemist recently took me to task for worrying about the politics of sexuality. “It’s all a matter of hormones,” he told me in earnest. “The research is moving fast and it won’t be long before we can control these things, once and for all.” Or is Nurture the problem? Careful, parents. Not so strong Mom. A little closer Dad.

Now a psychotherapist and two sociologists from the Kinsey Institute have added new coal to the fire. Using a statistical method called path analysis on data based on the childhood social and sexual behavior of 979 male and female homosexuals and 477 male and female heterosexuals, Bell, Weinberg, and Hammersmith offer a consolation to guilty parents that earned front page attention in the New York Times:

For the benefit of readers who are concerned about what parents may do to influence (or whether they are responsible for) their children’s sexual preference, we would restate our findings another way. No particular phenomenon of family life can be singled out, on the basis of our findings, as especially consequential for either homosexual or heterosexual development. You may supply your sons with footballs and your daughters with dolls, but no one can guarantee that they will enjoy them. What we seem to have identified — given that our model applies only to extant theories and does not create new ones — is a pattern of feelings and reactions within the child that cannot be traced back to a single social or psychological root; indeed, homosexuality may arise from a biological precursor (as do left-handedness and allergies, for example) that parents cannot control. In short, to concerned parents we cannot recommend any thing beyong the care, sympathy, and devotion that good parents presumably lavish on all their children anyway.

PATH ANALYSIS & MULTIPLE REGRESSIONMultiple regression is a statistical procedure intended to measure the effect of a group of independent variables X1, …, Xp, on a single other dependent variable, Y, and to test whether there is such an effect. In order to perform such a test, one must make assumptions about the nature of the relationship (that it is linear) and the nature of the distribution of the variation (or error) in Y for given values of X1, …, Xp (that it is “bell-shaped”). Path Analysis, a way of performing a collection of multiple regressions in a highly structured manner, is commonly used by sociologists and political scientists in the analysis of data from surveys. In order to do path analysis, one specifies the possible causal relationships among the variables before examining the date; e.g., C is influenced by A and B; E is influenced by A and C; and F by A, B, and D. Then one estimates the magnitude of these influences and tests whether they are sufficiently large (compared to the variability in the data) to be considered real. These tests are based on the same kind of assumptions about the nature of the variables being studied as in regression. Statistical procedures may be thought of as measuring devices that work well on particular kinds of material and not so well on others; they therefore must be applied thoughtfully (one wouldn’t use a microscope to look at the stars). However, even when applied appropriately, these methods cannot usually be regarded as definitive when applied to surveys. Conclusions drawn from them must be tentative, since these methods can do little more than suggest relationships or the lack thereof in social science data. |

The authors take care not to exceed the limitations of their method. Because path analysis can be used only to test existing notions, not to propose new hypotheses, the researchers cannot investigate possible biological pathways to homosexuality. But they can — and do — rule out nearly all of what must be an exhaustive array of social and psychological influences. The strongest factors remaining are “childhood gender non-conformity” and homosexual activities in childhood and adolescence. These factors are not causes of homosexuality, however; they merely reflect what seems to be an already deep-seated predisposition to homosexuality.

It is by a curious process of elimination, then, that the authors advance their suggestion that “homosexuality may derive from a biological precursor.” Their research furnishes no argument for a biological cause of homosexuality save the indirect evidence that all conceivable non-biological causes seem improbable. Throughout their analysis of social and psychological causes, however, the authors intimate that biology is to blame. Their final chapter, headed with the overt query “Biology?”, presents no evidence of a biological cause.

Why, then, after discarding the erroneous psychological and sociological explanations of the past, do the authors settle for the equally troublesome theory of a “biological precursor”? Ingenuous as it seems, their suggestive conclusion belies a deterministic view of sexuality that offers free reign to those, who, like my acquaintance the chemist, would use science to control such behavior.

It is almost tempting to criticize this study on its merits and flaws as scientific research. The relatively large size of their sample, which was gathered from beyond the usual collection of homosexuals in therapy or institutions, and the undoubtedly sincere attempt to use innovative and “objective” analytical techniques might all merit praise. However, the age of the data (a lot has happened to change homosexuals’ perceptions of themselves since 1969-70, when the interviews were conducted), the reliance on individual memories of childhood for hard data, and the sample distribution (all interviewees lived in the San Francisco Bay Area; most homosexual subjects were recruited through bars, organizations, and advertisements in movement newspapers) all detract from the validity of the conclusions.

But these are all secondary considerations. There is no need to worry about these details when we should be worrying about asking the wrong question. The question is not, Why are there homosexuals? but rather, What is a homosexual?

>> Back to Vol. 14, No. 5 <<

NOTES