This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The Road to the Holocaust: Nazi Science and Medicine

by Robert Proctor

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 14, No. 2, March-April 1982, p. 15 — 20

Robert Proctor is a Teaching Fellow in the History of Science Department at Harvard University.

Racist ideas go back a long time. Few of the famous 18th century European champions of liberty, fraternity, and equality could be considered today as anything but racists or sexists: Hume in his Essays compared the intelligence of the Negro to that of a parrot; Rousseau and Hegel both considered the minds of women not fit for the sciences or the arts.

And science as much as any other form of culture has been involved in the attempt to preserve social order; biology in particular has long served as a useful social weapon. In the late 19th and early 20th century, American and British social darwinists found in the theory of evolution by natural selection a kind of scientific guarantee of “cosmic optimism,” and evidence for the moral superiority of the emerging philosophy of competitive liberalism. Social darwinists in Germany also sought to ground their political predispositions on what they considered to be the “natural order,” but with a somewhat different emphasis. German social darwinists were no less enthusiastic about the struggle for existence in social life, but were much less optimistic about whether that struggle could be maintained, given the rise of democratic movements (such as the French Revolution), and the rise of welfare politics in medicine and social services. German social darwinians tended to reject the optimism of the laissez faire market popular in England and America, and stressed instead the need for state intervention to stop what they saw as the beginnings of a large-scale degeneration of the human species.

A Theory Based on Fear

In 1895, in the founding document of what came to be known as “racial hygiene” (Rassenhygiene — sometimes translated as “eugenics” in Germany,1 the physician Alfred Ploetz warned that the rise of democracy has created two great dangers that threaten the very survival of the “race”: first, because medical care for the weak has begun to destroy the natural struggle for existence; and second, because the poor and misfits of the world are beginning to multiply faster than the more talented and fit. Care for the weak may help the individual, but it endangers the race. Ploetz called for a new kind of hygiene, a “racial hygiene” which would consider not just the good of the individual, but also the good of the race.

Interest in racial hygiene grew through the end of the 19th century, and by the turn of the century, large financial interests had been attracted. In 1900, the arms industrialist Alfred Krupp sponsored a prize essay contest on the question of “What can the theory of evolution tell us about the internal political development and legislation of the state?” The prize of 100,000 Reichsmarks drew more than 80 applicants, and the ten winning volumes were published as a veritable encyclopedia of social darwinism, without equal in any other country. Four years later, in 1904, Alfred Ploetz established the Archive for Racial and Social Biology to investigate “the principles of the optimal conditions for maintenance and development of the race.” One year later Ploetz founded the Society for Racial Hygiene, which soon became one of the more important bio-medical societies in the country.

Two examples illustrate the fears in the Society concerning the degeneration of the race. In her article in the 1912 Archive,2 Dr. Agnes Bluhm criticized the racial effects of modern medical birth assistance. Fewer women, said Bluhm, die in childbirth, but this is precisely the danger, for it allows those women to survive and reproduce, who otherwise, without the intervention of doctors, would not be able to give birth. Bluhm argued that the incidence of incapacity to give birth (due to narrow pelvis, for example) is growing in the population, and supported this not only with data showing the increase in Caesarean sections (as if there weren’t other reasons for this!) but also with the supposed fact that the “natural peoples of the world” give birth without pain. Citing Wilhelm Schallmayer, winner of the 1900 Krupp prize, Bluhm ended her article with a warning to the effect that the more women rely upon medical aid to give birth, the more dependent upon that help they will become.

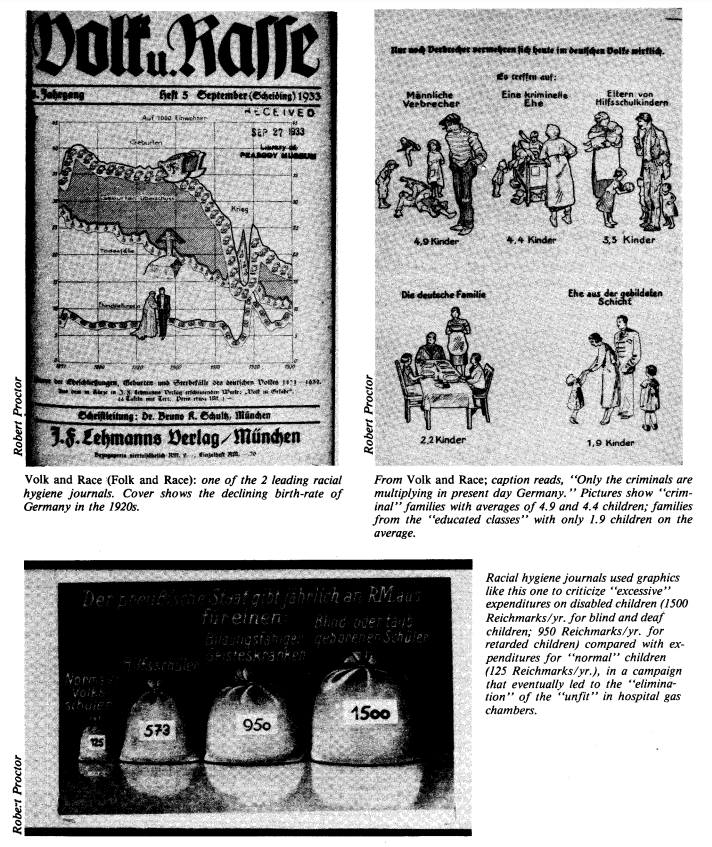

Related to this fear of the care for the weak, there was also a growing fear of what Dr. Hermann Werner Siemens called the “proletarianization” of the population, that is, the fear that the various “inferiors” of the world — not just the poor, but also the feebleminded and the criminal — were beginning to multiply more rapidly than the more “gifted” elements of society. In a 1916 article,3 Hermann Siemens, of the Siemens industrial concern, cited the Galton-Pearson estimate that the value of a man usually stands in inverse proportion to the number of his children. Siemens warned that the poor are outbreeding the rich, and illustrated this with birth rates from Vienna, Paris and Berlin, and then finally noted that his own illustrious family (of whose genetic excellence he had no doubts) averaged only 2.8 children per marriage. And unless the tide is stemmed, Siemens concluded, the best of human heredity will be swamped with a mess of inferior types.

A Perfect Marriage: The Nazi Era

The concerns of racial hygiene until well into the 1920s were largely what might be called “populational” or “meritocratic”: racial hygienists worried about the declining birth rate, about the disproportionate breeding of “inferiors,” and about the negative effects of social welfare medicine. But at least until after World War I, racism per se played a relatively minor role in the racial hygiene movement. The science of racial differences, growing out of phrenology, criminal anthropology, and so forth, was concentrated more in what was often called “social anthropology.” Until the early 1920s, the leading organ of the “Nordic” social anthropologists was a journal called the Political-Anthropological Revue, most widely known for its publication of articles purporting to demonstrate that the artist-engineers of the Italian Renaissance were actually blue-eyed blonds.4

With the rise of nationalism and severe unemployment after World War I, however, anti-semitic and anti-immigrant feelings began to grow, especially among professional classes. And by the early 1920s, these two trends — the racial hygienists, and the racist social anthropologists — had begun to merge. The Society for Racial Hygiene began to publish reports on racial differences, and the dangers of racial mixing; the Political-Anthropological Revue began to support its theories of “Nordic superiority” with arguments drawn from genetics and physiology. In 1930, with Nazism looming on the political horizon, Fritz Lenz, editor of the Archive, even suggested that there might not have been a Nordic movement, had it not been for Ploetz’s racial hygiene.

Racial hygienists greeted Hitler with open arms. In 1931, two years before the Nazi rise to power, Lenz praised Hitler as “the first politician of truly great import who has taken racial hygiene as a serious element of state policy.” Medical science, in turn, played an important part in national socialist ideology. Hitler was the “great doctor of the German people,” and Hitler himself lauded his revolution as the “final step in the overcoming of historicism, and in the recognition of purely biological values.”

It is often said that national socialists distorted science, that doctors and scientists perhaps cooperated with the Nazi regime more than they should have, and that by 1933, as one emigré has said, it was too late, and scientists had no alternative but to cooperate or flee. There may be some truth in this, but I think it misses the more important fact that it was largely medical scientists who invented racial hygiene in the first place. Professors of biology, medicine, anthropology, and law did not just cooperate in Nazi programs of racial destruction, but were often central figures in both the theory and the practice of those programs.

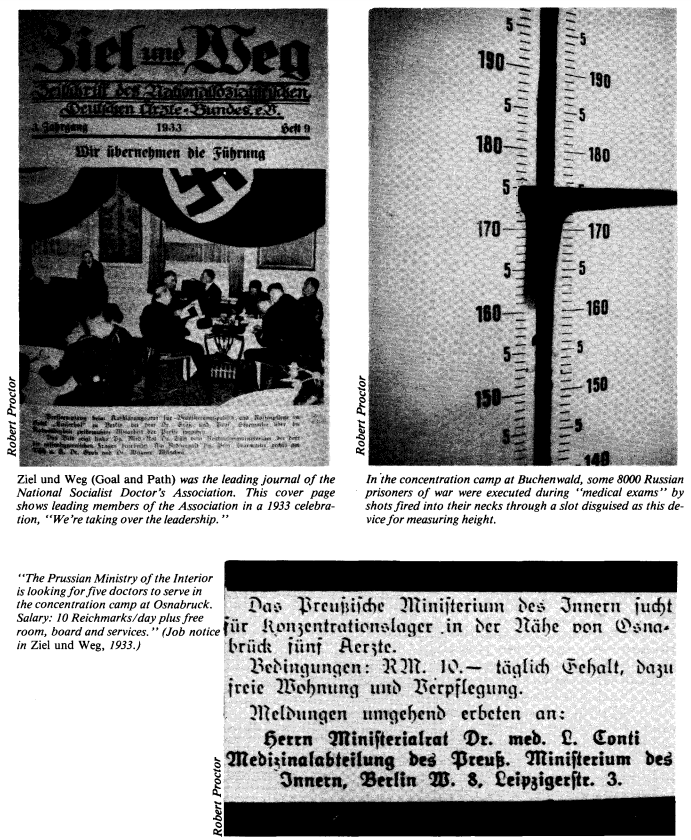

Even before the rise of national socialism, racial hygiene had become a respectable ideology in the German medical profession. Membership in the Society for Racial Hygiene grew rapidly in the years of the Weimar Republic, and by 1930, the Society boasted more than 1300 members — mostly doctors — in 16 local chapters with four more in Austria.5 Of the 26 professors offering courses in racial hygiene in 1932, some three-quarters had medical degrees. Medical men were among the earliest adherents of national socialism, and in the Reichstag elections that led to Hitler’s coming to power, nine physicians were elected as representatives for the Nazi party.6 In 1929, a small group of some of Germany’s leading physicians formed the National Socialist Doctors’ Association. The organization, representing the main medical wing of the Nazi party, was an immediate success, and by 1934 the rush of doctors wanting to join the group was so great that physicians were asked to hold off on applications until the present ones could be processed. By 1938, the membership in the Association had grown to over 30,000 doctors, representing some 60 percent of all physicians practicing medicine in Germany.

From Theory to Practice

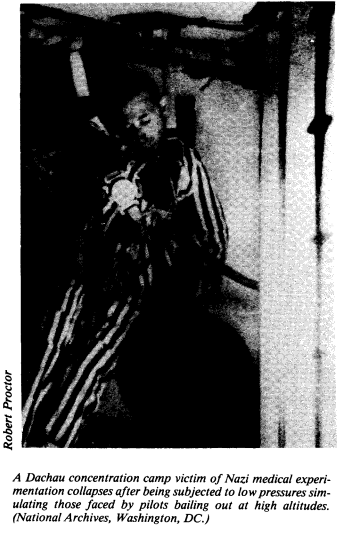

The two most important racist laws of the Nazi state in the 1930s were written, administered, and executed by leading members of the German medical (racial hygiene) community. In July, 1933, the Nazi state passed the Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring, according to which individuals could be sterilized against their will if, in the opinion of the newly established “Genetic Health Courts,” he or she suffered from any of various “genetically caused” illnesses, including feeblemindedness, schizophrenia, manic depressive insanity, genetic epilepsy, Huntington’s chorea, blindness, deafness, or physical deformity, and alcoholism. The law, according to which some 300,000 individuals were sterilized, was written by a lawyer and two doctors, one of whom (Prof. Ernst Ruedin) was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Psychiatry in Munich, one of the most celebrated research clinics in the world.

In 1935, Hitler signed into law the second major racial measure of the Nazi regime, the Law for the Protection of the Genetic Health of the German People. According to this law, couples were required, before marriage, to submit to a medical examination to see whether “racial damage” might be involved. Apart from disallowing marriage if one party was considered genetically defective, the law also forbade marriage between Jews and Aryans, with a later extension to cover gypsies, Slavs, and other races deemed inferior.

In 1935, Hitler signed into law the second major racial measure of the Nazi regime, the Law for the Protection of the Genetic Health of the German People. According to this law, couples were required, before marriage, to submit to a medical examination to see whether “racial damage” might be involved. Apart from disallowing marriage if one party was considered genetically defective, the law also forbade marriage between Jews and Aryans, with a later extension to cover gypsies, Slavs, and other races deemed inferior.

A third measure of Nazi medical policy brings us further into the realm of the criminal. On September 1, 1939, Hitler issued the enabling orders that certain doctors be commissioned to carry out the “mercy death” or euthanasia of patients in mental institutions judged to be suffering from incurable illnesses. This program was stopped in August 1941 largely as a result of church protest (other critical forces had been driven underground); by this time some 100,000 individuals had been killed in Germany alone, and many more in related programs in German-occupied areas. It is worth noting that doctors were never ordered to murder psychiatric patients and deformed children. They were empowered to do so, and fulfilled this task without protest, often on their own initiative. In the abortive euthanasia trial of 1964, Dr. Hans Hefelmann testified that “no doctor was ever ordered to participate in the euthanasia program; they came of their own volition.”7

An irony of Germany’s racial science is that many of its most important representatives considered their work to stand above politics. Fritz Lenz argued that racial hygiene was not a question of politics at all, that “the genetic quality of the race is a hundred times more important that the struggle between capitalism and socialism.” It may not even be surprising that many leading racial hygienists never even joined the Nazi party — scientists have considered their work apolitical in the midst of every conceivable form of domination and oppression. Nazi ideology itself was supposed to transcend all political differences; ideals of Family, Race, and Nation were to unite capitalist and worker, peasant and landlord.

Nazi racial hygiene in fact substituted a politics of race for a politics of class and social struggle. When the Moscow State Anthropological Museum opened its exhibit on Race and Race Theory in 1939, German racial hygienists wondered how the Soviets could portray Europeans as no less apelike than Africans, and how the Soviets could see the Nordic racial ideal as “nothing more than the desire of the dominant class to justify its dominion over the subjugated class as natural and biological.”8

Only in Nazi Germany?

After the war, physicians who had participated in the more brutal forms of destruction or experimentation were sentenced in the Nuremberg or Buchenwald trials. Scholars who had remained on the plane of theory were never touched — many racial hygienists were reappointed professors of human genetics at leading German universities. In recent years, largely as the result of the events of the 1960s, Germans have begun to explore this dark side of the history of science; people are beginning to wonder whether it is proper that former SS and SA9 functionaries sit on the board of directors of the German Medical Association, and whether it is proper for the German medical community to be directed by a former Colonel in the SA.

There is also a growing consciousness that racial hygiene was not just a German phenomenon, that in fact a large Nordic movement flourished in the United States long before the Nazis rose to power. The American Emigration Restriction Acts of 1924 and the various sterilization laws dating back to 1907 in the US served as models of racial policy to early Nazi medical men looking for international legal precedents.

There is finally a growing consciousness that racial hygiene may live under many different names, and that the past is very much still with us. Criminal biology, a major research area in Nazi science, is again on the rise. American research as recent as January 1982 purports to demonstrate that criminality is a genetic disorder.10 Hormones are being examined in search of the molecules which will explain why “what is” ought to be, whether this involves differences in the math ability of men and women, or differences in intelligence between blacks and whites. And the trend to blame the social order on a natural order is not restricted to the capitalist West: Dr. Guenther Doerner, endocrinologist at the Humboldt University of East Berlin, has recently conducted experiments in an attempt to prove that homosexuality in humans might be treated or even prevented by appropriate in utero injections of hormones into the developing fetus.11

In his 1954 history of the Destruction of Reason, Georg Lukacs argued that biologism (biological determinism) in philosophy and sociology has always been the basis of reactionary world views. Perhaps this has not always been the case — perhaps there have been times that nature has been appealed to in pursuit of genuine progress, or that organismic analogies have served to help bring down oppressive orders (one thinks of Enlightenment philosophy in the first instance, Hobbes in the second). But in the 20th century, and even much of the 19th, the appeal to biology as a source of inspiration for the structure of human society has played a largely conservative, and sometimes tragic role. Racial hygiene in Nazi Germany was an extreme case of “biologism,” but neither the first, nor certainly the last. It is a history that we have yet to conquer.

>> Back to Vol. 14, No. 2 <<

NOTES & REFERENCES

- Alfred Ploetz, Grundlinie einer Rassenhygiene, vol. I, Die Tuechtigkeit Unsere Rasse und der Schutz der Schwachen, Berlin.

- Agnes Bluhm, “Zur Frage nach der generativen Tuechtigkeit der deutschen Frauen und der rassenhygienischen Bedeutung der aerztlichen Geburtshilfe,” Archiv fuer Rassen- und Gessellschaftsbiologie, vol. 9, 1912, pp. 340-346.

- Hermann Siemens, “Die Proletarisierung unseres Nachwuchses, eine Gefahr unrassenhygienische Bevoelkerungspolitik,” Archiv fuer Rassen- und Gesellschaftsbiologie, vol. 12, 1916/18, pp. 43-55.

- Ludwig Woltmann, ed., Politisch-Anthropologische Revue, 1902-1922.

- Eugen Fischer, “Aus der Geschichte der deutschen Gesellschaft fuer Rassenhygiene, Archiv fuer Rassen- und Gesellschaftsbiologie, vol. 24, 1930, pp. 1-5.

- Albert Zapp, “Untersuchungen zum Nationalsozialistischen Deutschen Aerztebund,” Dissertation, Medical, University of Kiel, West Germany, 1979.

- Cited in Frederic Wertham, A Sign for Cain, New York, NY, 1966, p. 167.

- “Sovietunion,” Ziel und Weg, vol. 12, 1939, pp. 307-308.

- *The SS (Sehutzstaffel) and SA (Sturmabteilung) were select military units known for their dedication to Nazism.

- Richard A. Knowx, “New Study of Adopted Danes Suggests Genetic Link to Crime,” Boston Globe, January 8, 1982, p. 3.

- Guenther Doerner, ed., Endocrinology of Sex, Leipzig, 1974.