This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Unionized or Computerized: The Terminal Secretary

by Renate Lehmann Hanauer

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 6, November-December 1981, p. 19 — 24

Renate Lehmann Hanauer is a member of District 65, U.A.W., and a former activist and steward of its Boston University Local.

In recent years increased attention has been focused on all aspects of clerical work due, for the most part, to its rapid expansion. In 1979 18.2% of the entire workforce were clerical workers. In Boston clerical workers make up 22.8% of the total workforce, the third highest concentration in the country after Washington 23%, and New York 24%. About 85% of clerical workers are women.

Clerical work has replaced manufacturing as the single largest sector of the workforce. Consequently, managers in industries with large concentrations of clerical workers such as insurance companies, banks, publishers, as well as, non-profit organizations such as universities, have taken a hard look at the organization and productivity of clerical work.

New computer based technology applicable to office work is becoming available at continuously decreasing cost. At the same time, clerical workers have begun to organize to demand higher wages, better working conditions and more opportuities for advancement.

The Nature of New Technology

The first wave of workplace technology was the 19th century Industrial Revolution with the large-scale introduction of machines like the spinning jenny and the steam engine. In 1914, the introduction of the first assembly line by Ford revolutionized the automobile industry. By 1925 Ford was capable of producing almost as many cars in one day as had been produced in an entire year before the advent of the assembly line.1 In the course of history technological means have been refined and their use greatly expanded in order to increase production.

Now, with the advent of computers, particularly microprocessors, a quantum leap in the development and use of workplace technology seems to be taking place. In contrast to earlier forms of technology, computer automation is enormously flexible. This flexibility allows automation to be extended into areas where it has never been possible before, such as skilled work in the machine shop, the engineering department, and the office.2 In a recent issue, Business Week reports that some 38 million of the 50 million white-collar jobs in the U.S. will eventually be automated; according to estimates by experts, 45 million jobs, or 45% of all jobs, could be affected by factory and office automation.3

New Office Technology

The word processor has been the most widely introduced element of the projected “office of the future.” According to James W. Driscoll of the M.I.T. Sloan School of Management, word processing merely amounts to “mechanization,” the replacement of human labor by machine power. “True” office automation, in contrast, involves extensive discretion by machines. Such “true” office automation would restrict clerical work to an even greater extent and leave the clerical workforce with tasks that “do not form an integrated, purposeful whole which would engage the interest and attention of a human being.”4 Their only determining characteristic would be that the machine was incapable of doing them. While the office of the future may still be a little ways off, word processsing has definitely arrived and is growing rapidly. The unit of the word processing equipment actually used in the office is the video display terminal (VDT), sometimes also referred to as VDU (video display unit) or CRT(for cathode-ray tube), which is attached to a keyboard. This unit is connected to a computer. An estimated five to seven million workers in America now use VDTs and by 1985 there will be more than ten million VDTs in use. Word processors make storage and retrieval of information extremely efficient. The need for voluminous, cumbersome filing systems is eliminated as the information needed can be called up at the touch of a button.

Who Controls The Technology?

While technology sometimes seems to follow its own independent and inevitable course, it must be remembered that it is subject to human decision both in its development and use. The use of technology in the labor process is determined by the goals of industry and commerce, indeed the whole economic system. The ultimate goal of production, basically unchanged since the emergence of capitalism, is to maximize profits, not to meet human needs, whether material or psychological. These priorities must be kept in mind in evaluating the impact of technology on the individual worker.

Control and Productivity

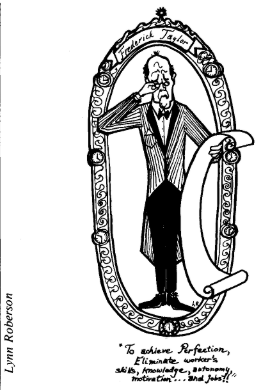

Management is guided by theories and principles first articulated by two nineteenth century engineers: Frederick W. Taylor and Charles Babbage. Taylor, the father of “scientific management,” realized that management’s power was imperfect as long as the individual retained a measure of control over his/her work. In general, the degree of worker’s autonomy is directly related to the degree of skill necessary for a particular job. Taylor devised ways to separate the worker from his skill and to transfer the planning functions of a job to management. Because of the reduced level of skill, the worker became more expendable, replaceable and, in the long run, paid less.

This process has increased management’s control over the work process as well as the workforce by the separation of hand and brain. Management has attained a monopoly over knowledge and the control of each step of the labor process and its execution.5 As the worker has been robbed of skill, autonomy, and pride in his/her work, motivation is decreased and alienation has arisen. Modern management has replaced the self-motivation of the worker with external material and psychological incentives, as well as increased supervision.

Taylor’s principles and methods of management, although refined, are still being applied. Modern management’s main concern has always been the “man problem,” which is, “nothing more nor less than the resistance of the worker to management’s expropriation of his skill and fruits of his labor, and to the gradual usurpation of his traditional authority over the work process.”6 It is management’s aim to control every aspect of the worker’s life on the job. The new computer technology is eminently suited to this end and often used accordingly. Hatley Shaiken, technical analyst and research fellow at M.I.T., points out that management’s intent in the development and use of computer technology is clear: “the elimination of skill, the basis for job control by workers … In the case of numerical control, the total elimination of skill is not inevitable but it is now possible.”7 Shaiken argues further that the issue is not skill as such, but “skill as a roadblock to managerial control over production.”8

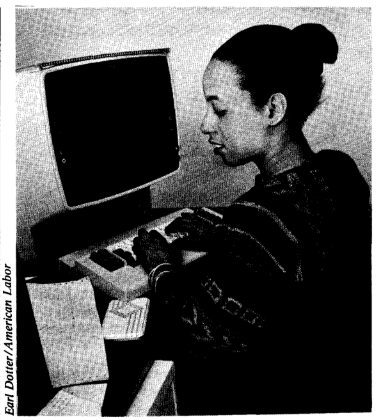

In the office, VDTs make possible a degree of control and supervision never realized before. VDT operators are virtually tied to their machines. The number of strokes, errors, etc. can be closely monitored and the temporary absence from the machnie can be recorded. In many cases, workers are not allowed to take their break when they would like to. The pace of work is set by management, and often judged by workers to be too fast. Robert Howard writes in an article on communications workers that

[c]lerical workers have been deeply affected by the dozen new computer-based administration systems introduced in the past decade. In one sense, computerization has made clerical work easier. Customer records are now at the tip of one’s finger instead of buried in mammoth files. But, … , computerization also brings centralization and a thorough reorganization of work that isolates clerical workers and subjects them to more rigid supervision and control.9

The assumption is that control and productivity are directly related. Both control and productivity are further promoted by the division of labor. The increase in productivity made possible by the division of labor was already recognized by Adam Smith. A further step in this process was pointed out by Charles Babbage in his book On the Economy of Machinery and Manufacture published in 1832. He shows that by dividing the work process into its components, by assigning different people to each task, thus turning people from skilled craftspeople into detail workers, and by paying workers at a different rate depending on the amount of skill necessary to perform each task, productivity is greatly increased.

Of course, the judgement of which jobs are skilled is highly arbitrary. “Women’s work” has always been economically devalued regardless of the actual skill required. However, Babbage’s principle is being applied as the secretary’s job becomes fragmented. The resulting jobs demand less skill, and are more boring and even more poorly paid.

Automation: Its Impact on the Worker

The growth of clerical work and its increasing cost, despite the low wages for clerical workers, has turned management’s attention to office productivity traditionally considered low. It is management’s aim to raise productivity by increasing the investment per worker in new machinery which has been low for the office as compared to factories and farms. This shift of office costs from personnel to equipment will mean that fewer people will be needed to do more work. Investment in expensive equipment may also lead to shift-work for clerical workers as companies try to get the most out of their investment. Another possibility under consideration is giving employees terminals so they can do computer work at home. This will probably mean more part-time work without benefits and security as well as piecework.

The division of labor for office workers is increasingly meaningless routine jobs. Supervision is becoming tighter and more pervasive than ever before. Clerical workers will be relegated to dead-end jobs with low pay. While automation can in some industries make working conditions safer, this is not the case with office automation.

Health and safety. There are a number of health and safety problems associated with working at VDTs including eye strain, headaches, back, neck and shoulder pains, fatigue, nausea and short-term loss of visual clarity. Although a study by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) concluded that VDTs do not represent a radiation hazard to the person working on or near a terminal,10 the overall long-term effects of working on VDTs for long hours are not known yet.11

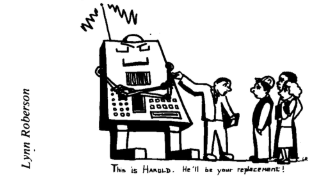

Unemployment. Since automation is designed to increase productivity so fewer workers can do more work, the question arises whether the new technology will displace workers. While the effects of displacement through automation are offset by the fact that clerical work will be the fastest growing occupation in the 1980’s, studies in France and Britain predict enormous job losses in the future.12 In an economy like that of the U.S. which already sustains a large unemployment rate, concerns about elimination of jobs are very real. Harley Shaiken writes, e.g., that “… microelectronics affects jobs in numerous ways . . . [it] extends to every sector of the economy. Office automation, for example, reduces the number of white-collar opportunities once available to blue-collar workers.”13 The precise impact of the new technology is difficult to assess. Whether new technology will result only in structural changes in the workforce or, as many people here and in Europe fear, in structural unemployment is not yet clear. However, the motivation for developing and introducing this technology in a capitalist economic system is to increase productivity by reducing labor costs. Unless there are forces to counteract these dynamics, it is fair to assume that automation may have a serious impact on unemployment.

Automation and the unions. We face a situation where technology is used to serve certain ends which are not in the interest of the worker. Since much of modern management is, however, an attempt to deal with the “man problem,” it follows that well-organized workers with clear goals might very well put a brake on management’s “human engineering” designs. But workers have to act soon, because automation can be and is being used to weaken existing organizations. In Shaiken’s opinion “new technology poses one of the most serious challenges that workers will have to face in the 1980’s.”14 The United Auto Workers has been under attack as automation is introduced on a large scale. The computerization of work “undermines union wages, thins the ranks of union membership, attacks the integrity of the bargaining unit and provides the techniques for the creation of a strike-proof workplace,” according to Robert Howard.15 Furthermore, new technology instills in workers a sense of powerlessness and inability to shape their work lives and thus serves to divide and demobilize them. Nevertheless, if, in Shaiken’s words, “labor does not find ways to control technology, then management will use technology to control labor.”16

Clerical workers are in a particularly weak position. Very few clerical workers are organized (11% overall, 6% in private industry), so office automation has met little resistance. In organizing clerical workers demands for increased pay and opportunities for advancement have been understandably paramount. Rapid automation, however, may make matters worse for clerical workers and change more difficult. The high degree of stress that affects clerical workers — results mainly from low pay, lack of respect, lack of promotions, monotonous work, lack of autonomy — is exacerbated by the introduction of office technology. Automation is likely to make a bad job worse, increase control over the worker, devalue skills and make work more boring while increasing its pace.

Change is not very likely without organization, and that means unionization. Recently Working Women, an organization of office workers with affiliates in twelve major cities has combined with Service Employees International Union (SEIU) to form Local 925 in order to make a push for organizing clerical workers. Working Women has issued an excellent report on the impact of office automation as well as a report on the hazards of office work.17

More Forceful Action is Necessary

Workers’ continuing problems with new technology indicate that existing organizations, especially unions, have not been able to deal effectively with office automation. In the past, unions have not done as much as they could have in exploring ways and developing strategies for action. They have, for the most part, dealt with the easier issues like wages, benefits and health and safety where management has been more willing to bargain. Their demands have been short-term, limited and parochial and have not challenged management prerogatives. For years this may have been acceptable to the rank-and-file workers, but it is no longer enough. On the technology issue the divergent interests of management and labor have sharpened to the point where workers are seriously affected. It is therefore necessary for labor to begin to deal with more fundamental issues. Now labor must begin to fight for participation in the decisions of how technology is used rather than merely react after all important decisions have been made. Such attempts to have input into the use of technology, however, “challenge the most sacred of sacred cows: managerial prerogatives.”18

UNIONS AND OFFICE AUTOMATIONTo meet the serious challenge technology presents labor, this country has a long way to go. According to a recent survey for the AFL-CIO Professional Employees Department, fewer than 20% of all contracts had any provisions dealing with technological change and of those that did, most “centered on smoothing workers adjustment to management-initiated and management-controlled change.”19 Typical contract clauses deal with:

The notification clauses generally provide for a very short lead-time, so that the union will find out about impending changes only from two to six months in advance. By the time the union finds out, management’s own position is in all likelihood completely finalized. Job protection is usually secured by the demand for training programs for employees affected by technological change and by ensuring that present employees will not be laid off or suffer a reduction in pay as a result of changed job specifications. In general unions do not participate in the early stages of planning nor have unions in the past done much to challenge management’s traditional right to make the decisions that affect the work process, i.e., the design of jobs, the role of technological means, the hierarchy of the workplace, etc. VDTs in Union ContractsWith regard to the technology of word processing health and safety questions are very prominent. Contract language accordingly deals with:

Some of these demands have not yet been won in collective bargaining, but represent union proposals subject to negotiations. District 65, U.A.W., which represents clerical and technical workers at Boston University, has made detailed demands regarding VDTs; but university management has responded only to demands dealing with technical aspects. The university will also make “an effort” to find another position within the university for an employee whose vision may be damaged by continued VDT work. Although not always central in negotiations, issues of new technology such as VDTs have been raised in other unions. Examples include the Communications Workers of America (CWA), the Office and Professional Employees International Union (OPEIU), and the Newspaper Guild. In California, Local 3 of OPEIU staged a four and a half month strike against Blue Shield and won cathode-ray-tube workers a guarantee of ”proper equipment” and a limit to speed and production quotas.20 Local 925 of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) negotiated an agreement with a Boston Legal Services office whereby individual secretaries can refuse to work at new IBM Mag Card word processors.21 In general, however, the vast majority of workers who work at VDTs have no protection whatsoever. |

Labor must develop strategies and programs that will lead to more labor input into these decisions. Obviously, this is not merely a question of technology, but of power. Labor’s limited success with regard to the effect of technology on the workforce reflects prevailing power relationships. It is necessary for labor to unite to meet this challenge and develop a joint strategy to deal with the effects of computer-based technology. In European countries where the level of organization is much higher than here important gains have been made in some areas with regard to automation. There are several things that seem to be especially important to meeting the challenge:

- Labor needs its own experts in order to evaluate new technology and its impact. Only this will enable labor to formulate its own position rather than be reduced to reacting to accomplished facts presented by management. No single union has the necessary resources to equal management, and concerted action is necessary.

- Education of rank-and-file members about the present and future effects of automation on their workplaces. Unless working people understand the importance of technology issues, they will not be willing to fight for them. In this country, unions have done little in this regard.

Unions in Europe, in contrast, have realized the importance of education about automation. In England mass education, local negotiating and shop-floor organizing has been stressed. In Norway innovative union education programs brought union members together with sympathetic computer technicians from the Norwegian Computing Center, a state-supported institution. Together they studied technology in the workplace which resulted in the formulation of worker alternatives to management’s plans for introducing new technologies. Both groups gained a new understanding: union members learned about computers, thus demystifying the subject, and computer professionals learned about trade unionism.22

- Unions have to demand that workers share in the gains of productivity through:

-

- a shorter work week

- longer vacations

- more breaks during the work day

American unions are beginning to move in this direction. Local 600 of the U.A.W. has made far reaching demands in a 1979 contract proposal, and the TOP (Technical, Office, Professional) Department of the U.A.W. has adopted a new technology resolution that calls, among many other things, for the establishment of communications, education, and statistics covering new technology.

It is certainly very difficult for workers to deal positively with new technology when it is the very technology that threatens to take away their jobs. Unions must work for full employment. These problems demand broad political solutions. As unions realize this they can take an active part in the introduction of automation.

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 6 <<

REFERENCES

- Harry Braverman, Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twenthieth Century (New York and London: Monthly Review Press, 1974), p. 147.

- Harley Shaiken, “Numerical Control of Work: Workers and Automation in the Computer Age,” Radical America, vol. 13, no. 6 (Nov.-Dec., 1979), p. 27.

- Business Week, Aug. 3, 1981, pp. 58-67.

- James W. Driscoll, “Office Automation: The Dynamics of a Technological Boondoggle,” M.I.T. Sloan School of Management Working Paper, No. WP 1126.80, May 1980, p. 4.

- See Braverman, chapter 5.

- David F. Noble, America by Design: Science, Technology and the Rise of Corporate Capitalism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977), p. 262.

- Shaiken, “Numerical Control,” p. 30.

- Ibid., p. 35.

- Robert Howard, “Brave New Workplace,” Working Papers for a New Society, vol. II, no. 6 (Nov.-Dec., 1980), p. 25.

- “A Radiation and Industrial Hygiene Survey of Video Display Terminal Operation,” in Select Research Reports on Health Issues in Video Display Terminal Operations, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, NIOSH, April 1981, p. 9.

- For more details on these problems see Science for the People, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 6-7.

- Race against Time: Automation of the Office: An Analysis of the Trends in Office Automation and the Impact on the Office Workforce (Cleveland: Working Women, 1980), p. 19. Science for the People published a condensation of this study in vol. 13, no. 3, 1981.

- Harley Shaiken, “Microprocessors and Labor: Whose Bargaining Chips?” Technology Review, Jan. 1981, p. 37.

- Harley Shaiken, “Detroit Downsizes U.S. Jobs: The New ‘World Car'” The Nation, Oct. 11, 1980, p.25.

- Howard, “Brave New Workplace,” pp. 27-28.

- Shaiken, “Detroit,” p. 37.

- Race Against Time (see note 12); and Warning: Health Hazards for Office Workers: An Overview of Problems and Solutions in Occupational Health in the Office (Cleveland: Working Women, 1981).

- Shaiken, “Numerical Control,” p. 37.

- See American Labor, no. 13 (1981), p. 4.

- Barbara Garson, “The Electronic Sweatshop: Scanning the Office of the Future,” Mother Jones, vol. 6, no. 6 (July 1981), p. 38.

- American Labor, p.4.

- Dennis Chamot and Michael D. Dymmel, Cooperation or Conflict: European Experiences with Technological Change at the Workplace, A Publication of the Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO, p. 27.