This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

‘Launch On Warning’: The Pentagon’s Computer Game

by Virginia Schaefer

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 6, November-December 1981, p. 25 — 30

Virginia Schaefer is active in Boston SftP, the Jobs with Peace Campaign, and High Technology Professionals for Peace.

“It’s a computer problem.” In response to gripes about bills and bank statements, this is becoming the standard answer. Increasing use of computers in everyday devices like cars and appliances, as well as for business transactions, means more chances for computer-related problems. And whether through ignorance, indifference, or assumption of well safeguarded design and manufacture, people are accepting computerization as worth a certain amount of risk.

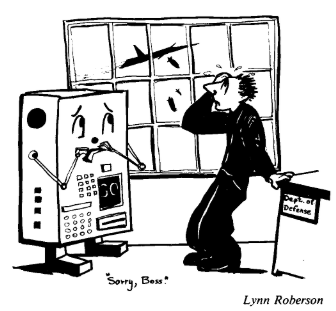

But when several recent computer errors came dangerously close to triggering a chain of events leading to nuclear war, many people reacted with shock and outrage. A serious error in the design, equipment, or operation of the U.S. nuclear-attack warning system may have the effect of, for example, a heart pacemaker’s total failure — multiplied by millions of lives. With publicity about the attack-warning computer errors of the past couple of years has come exposure of a rather alarming state of events. Countless lesser but potentially dangerous computer errors and ambiguities occur in the U.S. nuclear attack-warning system on a routine basis. (See box, “U.S. Military Computer Errors”.)

News of these errors has renewed apprehension about a system the Defense Department has been considering for over a decade: launch on warning (LOW). This C3 (command, control, communication) system would leave the decision to launch an ICBM attack entirely to machines. The version most often considered would allow only a “yes-no” prerogative to the President or his proxy and would be targeted against cities (countervalue). The strategic rationale for launch on warning is assurance that U.S. land-based missiles can leave their silos before Soviet missiles destroy them.

LOW and the Land-Based Missile System

The launch on warning concept was formulated as a protection against the threat of a Soviet first strike against U.S. land-based missiles (i.e., counterforce targeting). As targeting capability has become more precise by both superpowers, the U.S. has given increasing priority to protecting against a Soviet first strike.

Of course, U.S. targeting capability is also becoming more precise, with the same option of counterforce that the U.S. military fears in the Soviets. But the growing number of U.S. counterforce-capable weapons particularly the small; tactical ones, are presented in U.S. strategic doctrine as more “humane” than countervalue targeted weapons, since counterforce targeted weapons would supposedly do less damage to humans in a “limited” nuclear war. That the U.S.S.R. could perceive a first-strike threat from precisely targeted — possibly counterforce — American ICBMs has been pointed out by critics of U.S. strategic doctrine.1 Fears have also been raised of a Soviet LOW system in response to U.S. deployment of larger and more accurate missiles, such as those designed for any of the proposed MX systems.

Protecting all three “legs” of the U.S. nuclear weapons triad is central to U.S. declared strategic doctrine. The rationale is that the U.S. would not be able to respond effectively if the Soviets were allowed to knock out most U.S. ICBMs in a first strike. The extreme unlikelihood of an all-out Soviet preemptive first strike will be discussed later. But the possibility of Soviet missiles begin targeted against U.S. ICBM’s will remain as long as the U.S. has counterforce capability itself. And as long as the U.S. pursues protection of land-based missiles against a Soviet first strike, LOW will remain on some Pentagon “back burner,” still in range of possibility.

Launch on warning is one of three basic systems considered for protection of land-based missiles. One of the other methods is destroying or disarming incoming Soviet ICBMs with non-nuclear or nuclear detonations near the targeted silos. Aside from the still operative SALT I ban on anti-ballistic missile technology, the drawbacks of ABMs are their expense and technical difficulties of deployment, the dangers to the American populace from ABM detonations, and their tendency to provoke escalatory countermeasures.2

The second means of protecting land-based missiles is a mobile basing system. Over the past several years, the MX system has been promoted by many military people and resisted, with partial success, by many opponents. In the MX system, large counterforce-capable ICBMs would be shuttled along tracks connecting numerous heavily protected shelters or launching sites. In theory, this shell game would prevent the Soviet Union from being able to target the missiles accurately enough to destroy them. The main arguments against the MX include its huge economic and environmental costs, the long time needed for construction and testing, and the possibility that by the time of completion the Soviets might simply have increased their ICBM forces sufficiently to target all MX launching sites.3

The remaining land-based missile protection system is launch on warning. LOW’s primary purpose would be deterrence; the U.S.S.R. would not want to waste its missiles firing at silos which would be empty by the time the targets were struck. The other advantages of LOW are the preservation of U.S. missiles and the assurance of a quick and effective second strike. With the usual assumption that LOW would be triggered only by an all-out Soviet attack, there would be no point in targeting any U.S. missiles, since all Soviet missile silos would presumably be empty. In the same vein, there would be little point in keeping some counterforce-targeted missiles from being triggered by LOW, since an all-out Soviet attack would presumably target all U.S. land-based missiles. Launch on warning would not be a weapon, thus its implementation would give its users the political advantage of appearing non-aggressive, interested only in deterrence and effective defense.

Many opponents of launch on warning focus on its technical imperfectability. It is widely assumed that technical fallibility is the main hindrance to its implementation. But the LOW issue involves a complex of political, as well as technical, forces.

Minor Technicalities?

The basic technical question about launch on warning is “Could it be made absolutely reliable?” Even for supporters of the LOW concept, the answer is “no.” Former Livermore Weapons Labs director Herbert York, writing against LOW in 1969, saw launch on warning as “technically viable,” yet feared the consequences under LOW of not only a small or accidental Soviet attack, but of a “false alarm” as well.4 Today, after years of military computer errors, no one foresees a 100% reliable launch on warning system.

Herbert Scoville, former Deputy Director of the CIA, also opposes development of launch on warning. He says that even with improvements to technical components of LOW, ” … my worry would always be that they might malfunction at some point, and I don’t think the fate of the world should depend on computers.”5

Progressive science commentator Nigel Calder has pointed out that the mere appearance of interference with electronic reconnaissance or communication could precipitate a disastrous reaction. This kind of situation could arise under a LOW system. In 1975, for example, the U.S. military readily assumed that the temporary dazzling (sensory overload) of an early-warning satellite over Siberia was the result of a secret Soviet anti-satellite device. Observers waited long enough to find out that the cause of the problem was a large gas pipeline fire. Had the incident occurred during a time of high international tension, such a fluke might have triggered a nuclear war.6

Political-Strategic Factors

Military strategist Richard Garwin considers launch on warning a necessary deterrent to a Soviet first strike. Since under LOW none of U.S. land-based ICBMs would be targeted counterforce, implementation of the system would give the U.S. no capability to launch a preemptive first strike. Garwin admits that even with his proposed elaborate safeguards, the chance of LOW error would remain. But he considers launch on warning morally superior — enough to make that risk worth taking.7

Garwin’s argument appeals to the deeply rooted U.S. military self-image as a peaceful champion of deterrence. At the same time, it supports a hair-trigger readiness to enter a nuclear conflict.

Launch on warning’s implementation could only exacerbate tension between the superpowers, making a missile launch more likely. An article in The Nation on a recent erroneous attack alert pointed out that although disaster had been averted again, “In a climate of extreme international tension, jittery generals and a jittery President might regard erroneous signals of an attack with less skepticism and set in motion drastic and irreversible procedure.”8

Launch on warning has also been opposed on civil liberties grounds. Sidney Lens, progressive critic of U.S. military policy, deplores the launch on warning concept, which he envisions as giving “generals, surveying radar and computers” the power to launch an attack. This situation, he contends, would allow even less input to war-waging decisions than in recent years, when the President has been taking over Congress’ previous power to declare war.9

Herbert York deplores the idea that under LOW only a “preprogrammed President” would have input to the decision on whether to launch U.S. ICBMs. He called it “morally and politically unacceptable” that such a terrible decision be made, on incredibly short notice.10

Launch on warning assumes the ability of an individual to act, simultaneously, with the political expertise of a national leader and with the automatic efficiency of the Air Force personnel now responsible for turning the Minuteman launch keys on command. The Presidential veto power allowed in most proposed versions of LOW is nearly useless, since there would not be enough time to make even a technically, and certainly not a politically, well-informed decision. As summarized by Nigel Calder, even if the President were presented with overwhelming electronic evidence of an oncoming missile strike, he might ” … refuse to take the irreversible step into oblivion until the warheads have begun exploding; he has, after all, good reason to be inhibited.”11 This inhibition — human wisdom, really — would counter the entire purpose of launch on warning.

U.S. Military Computer Errors: No End in SightTwenty-seven major U.S. military command posts around the world are linked by a network of satellites, radar stations, sensors, and warning systems. This network, called Wimex (World Wide Military Command and Control System) was started in 1962 following the Cuban missile crisis. Wimex was designed to provide attack warning and coordination of U.S. military activities all over the world. Since its inception. Wimex has been plagued by malfunctions. In 1967, for example, during the Arab-Israeli war, an American Warship was fired on because a computer error had kept it from receiving warning information. The 1968 seizure of the U.S.S. Pueblo might have been averted if a warning message to the ship hadn’t been misrouted by a computer. In 1973, an alert went out to all American ICBM and Strategic Air Command bases when a computer erroneously predicted that a Soviet test missile would land in California, instead of Siberia where it was targeted. During the 1978 Jonestown, Guyana emergency, Wimex was out of commission for over an hour due to computer problems following a brief power outage. To eliminate the problems, the Pentagon in 1970 began a standardization project. After 10 years and $1 billion, Wimex still suffers numerous shortcomings. In 1979 Congress, cut several million dollars from the Wimex budget and ordered it slated for replacement. A top C3 official has complained that stinginess with computer funding results from C3’s lack of “glamour.” As a Navy Admiral has stated, “I’d really wonder about an officer who wanted to make a career in computers’· Possible disasters arising from the frequent refusal among the armed forces branches to coordinate and share data are apparently not considered important enough to override traditional jealousies. In short, possession of nuclear weapons appears to be much more important to the U.S. military than their reliable and “safe” deployment. Attack-Alert Near MissesWithin the Wimex network, the North American Aerospace Defense (NORAD) center in Colorado is one of the four command posts where all information transmitted by satellite and radar is routed for evaluation and further action. In November 1979, an attack-simulation program inadvertently introduced into the NORAD computer system gave indications that a mass nuclear raid was underway. This caused all ICBM bases to be put on low-level alert, ten jet fighters ordered aloft and many more planes on standby, and all air traffic control centers over the U.S. to be notified to prepare to clear the airways. The ICBM low-level alert involves removing “attack verification codes” and missile launch keys from strong boxes and inserting the keys into their slots. If coded order to launch match the codes at the sites and if two pairs of Air Force personnel turn the key within a few seconds, an ICBM is launched toward a target in the U.S.S.R. That particular computer error was discovered within six minutes, before any irreversible steps toward nuclear war had been taken. A similar false attack alert took place in June 1980, when a faulty integrated circuit in a NORAD computer showed missiles traveling toward the U.S. Prior to 1979, such false alerts, serious enough to necessitate a “threat assessment conference,” had occurred every few years; from October 1979 to June 1980, four such incidents took place. Following the June 1980 false alert, Senators Hart and Goldwater of the Armed Forces Committee were assigned to investigate. Among their findings were overly fragmented management of the missile-warning system, and long delays in procurement of missile-attack warning data processing equipment. Some of the needed technical changes at NORAD had been made or were underway, among them installation of an off-site test facility so that war games could not be mistaken for the real thing and a display of the information concurrently transmitted to the other command centers. Especially important was the institution of cyclic redundancy checks, an essential error-checking routine to eliminate error in transmitted and received data. However, it is impossible to assure that false alerts will never occur. Cyclic redundancy checks, like other electronic safeguards, cannot ensure detection of 100% of data transmission errors. As Hart and Goldwater stressed, ”There’s no guarantee that false alerts will not happen in the future. They will occur and we must rely on the collective judgment of the people manning the system to recognize and deal correctly with false alarms.” Sources“The Nuclear Trigger” and D. Shapley, “The Fragile System,” Life 3:8, Aug. 1980, 22-30; W.J. Broad, “Computers and the Military Don’t Mix,” Science 207, March 14, 1980, 1183-1187; “Recent False Alerts from the Nation’s Missile Attack Warning System: Report of Senator Gary Hart and Senator Barry Goldwater to the Committee on Armed Services. United States Senate, October 9, 1980,” Wash.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1980. |

Push for the Shell Game

The Defense Department’s continued quest for land-based missile protection is rooted in the assumption that the U.S.S.R. could and would launch an all-out attack against U.S. land-based missiles. That assumption is false. In the first place, the theoretical accuracy of Soviet missiles is greatly exaggerated, since the missiles’ actual flight paths can never be tested for atmospheric, gravitational, and magnetic effects. The “fratricide effect” — disabling of incoming warheads by preceding detonations — also makes an all-out Soviet strike appear extremely unlikely to succeed.

In reality, there is little motivation for an all-out preemptive first strike, because even if the strike succeeded in destroying most U.S. land-based missiles in their silos, two-thirds of U.S. nuclear forces-submarines and bombers-would remain. Paul Warnke, former Arms Control and Disarmament Agency Director and SALT negotiator, has stated that “… no aggressor could see any advantage in an attempt against impossible odds, to destroy what would be less than a third of our strategic nuclear force.”12

The Defense Department continues to give thumbs down to launch on warning for the wrong political reasons. A 1979 Rand Report on “launch under attack” (another term for LOW) argues for pursuing an MX system, on grounds of its greater “flexibility.” Launch under attack, according to the report, would “give the Soviets control over when our ICBM force was used.”13 The apparent objection is to LOW’s limitation in response to direct attack-launch on warning is not handy for fighting a limited nuclear war, and it is certainly useless for a U.S. strike against Soviet land-based missiles.

Several critics of LOW who believe in the ICBMprotection line have raised the spectre of accidental LOW -instigated holocaust to bolster support for the MX. The Economist, in an editorial elicited by a recent U.S. attack-warning computer error, proclaimed that the mishap was proof that ” … the idea known as ‘launch on warning’ is madness.”14 The piece concluded that pursuit of an MX system is the best way to avert death by computer.

A recent Aviation Week and Space Technology News editorial made a more detailed but essentially similar argument. Decrying the continued dithering over choice of MX basing modes, it warned that “Airborne alert, as well as some of the other MX basing modes, drives U.S. nuclear strategy toward launch on warning.”15 The MX shell game is promoted as a more secure alternative to the LOW computer game.

With a Bang, or …

Randall Forsberg, director of the Institute for Defense Disarmament Studies, maintains that a totally automated launch on warning system will never be implemented. Yet she foresees development of and response of smoothly interlocking procedures for evaluation of and response to indications of a missile launch — a more streamlined version of the present early warning network. This system would enable U.S. missiles, in some circumstances, to be launched while under attack.16

Clearly, there is ever increasing military reliance on the kind of C3 electronics that a launch on warning system would utilize. LOW may not have to be an all-or-nothing phenomenon — perhaps it is already creeping up on us. William Perry, recently retired Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, avidly supports increased nuclear weapons development and maintenance of an American lead in military electronics. Yet, regarding launch on warning, “Perry says he cannot even discuss this option ‘without breaking into tears.’ Fundamentally, it ‘amounts to turning over the decision to start World War III.’ Perry says his enthusiasm for electronics does not extend that far.”17

This statement sounds a bit ludicrous, and coming from someone as highly placed in military administration as Perry, more than a little frightening. He champions the military goal of protecting land-based missiles at a high cost — he supports the MX system despite acknowledged problems. Given such a goal, it seems possible that the electronics he pushes might someday be used to develop a launch on warning system, or at least a system that approaches LOW in hair-trigger potential.

Launch on warning should be opposed by progressives in the context of the Pentagon’s dangerous and wasteful doctrine of land-based missile protection. Opposition to this doctrine has become more urgent with Reagan’s recent decision to deploy MX missiles in single, fixed silos, protected by either an ABM system or launch on warning. LOW’s technical faults, enumerated by moderates and even militarists, can certainly lend support to progressive opposition to the launch on warning proposal. But only through a fundamental change in U.S. strategic policy will the launch on warning system, as well as the MX and the ABM, be permanently laid to rest. Effective opposition to the Pentagon’s quest for a solution to the imaginary land-based missile protection “problem” must be part of the growing citizen movement against U.S. nuclear warmongering.

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 6 <<

REFERENCES

- R.C. Aldridge, The Counterforce Syndrome, Wash.: Institute for Policy Studies, 1978 (rev. 1979); B.T. Feld, and K. Tsipis, “Land Based Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles,” Scientific American 241:5, Nov. 1979, 50-61; J. Elmer, “Presidential Directive 59: America’s Counterforce Strategy,” Philadelphia: American Friends Service Committee, 1981; “What You Need to Know About: The New Generation of Nuclear Weapons,” Washington, D.C.: Institute for Policy Studies, 1980; Andres and Alexander Cockburn, “The Myth of Missile Accuracy,” The New York Review of Books, Nov. 20, 1980, 40 ff.; V. Perlo, “The Myth of Soviet Superiority,” The Nation 231:7, Sept. 13, 1980, 1 ff.; Boston Study Group, The Price of Defense N.Y.: N.Y. Times Books, 1979.

- See H.F. York, “Military Technology and National Security,” 1969, in Progress in Arms Control?: Readings/rom Scientific American, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman & Co., 1978,44-56.

- See Scoville, “America’s Greatest Construction: Can It Work?” The New York Review of Books, March 20, 1980; R. Burt, “MX Missile Could Mark Big Switch in U.S. Nuclear Policy,” New York Times, June 16, 1979, 5.

- York, op. cit, 96.

- “All Things Considered,” National Public Radio, June 17, 1980.

- N. Calder, Nuclear Nightmares, N.Y.: Viking, 1979, 96.

- See “Command and Control: Use It or Lose It?” F.A.S. Public Interest Report 33:8, Oct. 1980, 1 ff.

- C. Hanson, “Doomsday Option,” The Nation 231:22. Dec. 29, 1979, 676-677.

- S. Lens, “The Doomsday Prerogative,” The Progressive 45:1, Jan. 1981, 10. Also see Lens, The Day Before Doomsday, Garden City: Doubleday, 1977.

- York, op. cit., 96.

- Calder, op. cit.

- P. Warnke, “Countdown on the MX Missile,” Boston Globe, Aug. 30, 1981, A4.

- “Launch Under Attack (LUA): An Assessment of Minuteman Targeting Options,” Rand Report R-2514-AF, Aug. 1979, declassified portions.

- “Doomsday by Short Circuit?” The Economist 275:7137, June 14, 1980, 18.

- W.H. Gregory, “Wrestling with MX,” Aviation Week and Space Technology 115:8, Aug. 24, 1981, 11.

- Interview, Brookline, MA March 1981. Also see Forsberg, “Military R&D: A Worldwide Institution?” Proc. of the American Philosophical Society 124:4, Aug. 1980, 266-270

- E. Marshall, “William Perry and the Weapons Gamble,” Science 211:13, Feb. 1981, 681-683.