This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The Basic Economics of “Rearming America”

by James M. Cypher

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 4, July/August 1981, p. 10–15 & 40–41

Preying on the fears of the military intentions of the USSR, carefully nurtured for the past 30 years, the U.S. government has made increased military spending a national priority. This call to “Rearm America” needs to be critically evaluated. It is time to ask:

—Is the Soviet Threat all we have been led to believe? Or is it designed to whip-up patriotism and blind support among U.S. citizens for an escalating military budget and an expansionary foreign policy?

—Will increased military spending alter geopolitical tensions? Or will it temporarily eliminate slumping corporate profits?

—Will increased military spending actually i-prove the defense capability of the U.S.? Or will it produce more inefficiency and more of the same type of traditional weaponry which is presently held to be inadequate?

—Will science continue to be subordinated to Cold War objectives)? Or will science work to solve the human needs and productivity crisis?

—Must we continue to repeat past mistakes? Or will we learn some historical lessons and find new solutions to the domestic and international economic crisis?

Both President Reagan and his Secretary of Defense, Caspar Weinberger, have proclaimed that their proposal to raise military expenditures, while slashing social spending, is part of their policy of “Rearming America”. The objective of current policy is to push for a massive military buildup much like that realized in 1950-52. The parallels with the 1950 period are amazing.

In 1950 State Department policy planners were alarmed by events which they felt signalled a shift in the international configuration of political-economic power. In August of 1949 the Soviets exploded their first A-bomb, thereby shattering the illusion of overwhelming U.S. technological military superiority. In late 1949 pro-Soviet forces emerged victorious in the civil war in China. Then, in June 1950, the U.S. entered into war in Korea.

In the late 1970’s alarm was spread by the announcement of the U.S. government that the Soviets were “outspending” the U.S. on armaments, and would soon surpass the U.S. in overall military prowess. Then in early 1979 the U.S. lost its Iranian ally in the economically significant Middle East. Finally, in late 1979 the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan allowed cold warriors to again raise the specter of an ever-expanding Soviet Union. A similar cry had been raised over Korea. In 1949-50, then, the surface issues were the loss of the nuclear monopoly, China and Korea. In 1979-80 they were overall weaponry expenditures, Iran and Afghanistan.

There were, of course, economic parallels too. After the postwar boom of 1947-48, the U.S. economy slowed down in 1949 and 1950. One popular view was that the U.S. was about to enter into another Great Depression. In 1979 the U.S. economy slowed and business analysts almost universally held that a serious recession was imminent. It was within the context of political-economic crisis that in 1950 a State Department policy planner, Paul Nitze, enumerated the policy of containment militarism in a classified position paper known as National Security Council Document 68 (NSC-68). It was the adoption of the proposals of NSC-68 that led to the expenditure of over $2 trillion for the military in the 1950-72 period. Thus it is of some significance to note Nitze’s present views as recently proclaimed in the influential journal Foreign Affairs: “Providing for the common defense now requires the kind of priority that it had in 1950, and it is a disservice to the American people to pretend that this can be accomplished without a major adjustment in national priorities. . . . “1 In NSC-68 Nitze urged that the U.S. deal with the alleged Soviet plan for world domination by building “offensive forces to attack the enemy and keep him off balance.” The aggressiveness of NSC-68 reveals the strategic objectives of U.S. policy at that time.

In 1950 several prominent and powerful individuals created a group known as the Committee on the Present Danger (CPD) to try to convince the U.S. populace that the militarized economy and society envisioned by NSC-68 should become a reality.2 Achieving success by 1952, the CPD disbanded. A second CPD was formed in 1976, again drawing on a small number of powerful policy-makers and influentials, this time to again convince the U.S. populace that it had to drop its anti-militarist sympathies to counter a growing Soviet threat. Both then and now the backdrop was one of U.S. economic crisis. Military spending, behind the veil of an external threat, was thought to be the way to transcend the crisis while restoring both U.S. dominance over the world order and high corporate profits.

The Capitalist Threat

In the present economic era of stagnation, coupled with unprecedented international competition many industries such as autos, shipbuilding, steel, electronics and aerospace have seen the domestic market falter and their rate of profit tending toward decline. It was in this historical context that military expenditures began their continued rise since mid-1979 as the “Vietnam Syndrome” was beaten back by a deluge of Cold War propaganda. The U.S. business press duly noted and championed this change of emphasis. Business Week (4/7/1980), for example, in the headline of one of its numerous articles on military expenditures in recent years noted that, “Congress Goes Wild on Defense Spending”; while Fortune (1/26/1981) proclaimed, “Happy Days Are Here Again for Arms Makers”.

In this context the case of the near bankrupt Chrysler Corporation is illuminating. While it is a widely recognized and often deplored fact that Chrysler has received two federal loan guarantees to stave-off financial disaster, Chrysler’s real rescue via military spending is virtually unknown. Chrysler’s largest customer is now the U.S. Army. Chrysler, long the sole maker of U.S. main battle tanks, received a lucrative contract (presently valued at $19 billion for work through the 1980s) to build the XM-1 tank, in the mid-1970s. In design and development for several years, the company is delivering its first XM-1’s in 1981 for $600 million. For fiscal year 1982 the Reagan ad-ministration plans to jump Chrysler’s order to over $2 billion. Such huge orders should definitely save Chrysler from bankruptcy because the rate of profit on its tank contract is a whopping 78% on equity capital.3 Meanwhile, as is invariably the case, the government will get only 254 rather than 309 tanks in 1981, while the price has shot-up 380%—from an agreed contract price of $560,000 to $2.7 million each. (The power-train on the tanks furthermore, will fail 61% more often than allowed under original contract specifications.)

The Chrysler case illustrates four things that have become constants in the military market. First, the demand for military hardware goes up when domestic non-military sales go down—i.e., military spending is a prop to industry rather than a reaction to the alleged Soviet threat. Second, the rate of profit on military work is much higher than on domestic work. For Chrysler in 1979, when their profit rate was 78% on military work, their civilian rate of profit was negative. For industry as a whole over a long period of time military contract profits have averaged 56% on invested capital—i.e., over 300% higher than the average received on civilian work. Third, the average rate of cost overruns—i.e., the difference between what the Pentagon agrees to pay for military products and what it actually does pay upon contract completion, averages 300%. Chrysler’s overruns, then, are “only average.” Fourth, weapon systems normally fail to operate at contract specified levels of efficiency, and the more complex they become the more probable their failure.

The above summary of Chrysler’s tank-building history can be repeated time and again. For example, the major airframe contractors, such as Boeing, Lockheed, and McDonnell Douglas experienced a 42% drop in 1980 in commercial orders of jet aircraft. As a result, Boeing has been put to work on air-launched cruise missiles, a $3.1 billion helicoptor contract, and the avionics for the B52, while Lockheed will design the Trident II and McDonnell Douglas will build the F15 for the Air Force and the F18 for the Navy.

What is most interesting in the case of Chrysler and the commercial jet builders is how closely the Soviet threat parallels the industrial needs of the largest U.S. corporations. In fact, the close parallel can only be accounted for by realizing that the U.S. government is using the bogey of the Soviet threat to pinpoint outlays that will serve as an industrial profit recovery plan. (Or in the words of Secretary of Defense Weinberger, the arms buildup is ”the second half of the administration’s program to revitalize America.”) Responding to the big military contract buildup from late 1979 to late 1980 corporate stock prices for firms known to be in the “electronics warfare group” jumped 100% in price while “defense issues” as a whole leaped 50% in the same time period.4

Any modern analysis of business cycles will stress the critical role of corporate investment in maintaining high levels of production, output and employment. The full significance of the military market is best understood in terms of its countercyclical role in sustaining corporate investment, production and employment. For example, in the second quarter of 1980 GNP fell further and faster than at any time in the entire post-WWII period. Speculation that the economic situation might duplicate that of 1929 was widespread. Then, almost as suddenly, the recession of 1980 was over. Few noted that one of the major reasons for this reversal was the huge jump of roughly $25 billion in new military contracts issued in fiscal year 1980. (Easy bank credit extended to corporations and a rapid run up in the money supply also greatly contributed to this turnaround.) Military prime contract awards jumped 35% above 1979 levels in the critical second and third quarters of 1980, while the hard pressed manufacturing sector saw their military contracts increase 48%. Although the demand for investment goods was weak in 1980, the business press clearly recognized that the demand for such goods (particularly aircraft) was buoyed by the military market in the later half of 1980.5 Since the Reagan administration plans to increase military contracts by $24 billion in fiscal year (FY) 1981 and an astonishing $44 billion in FY 1982, a similar stimulus to industries otherwise in decline is to be anticipated.

The most important lesson to grasp concerning the rapid arms buildup in this period was that these spending increases were not primarily devoted to high-tech exotica such as the MX missile system. Rather they were devoted to such mundane outputs as tanks, airframes, parts and shipbuilding. After years of stagnation, the U.S. is locked-into a massive shipbuilding program that will eventually raise the Navy’s fleet from 450 ships to 700 or 800 by 1995. For the collapsed U.S. metal-manufacturing sector (autos, parts, steel, aluminum, the machine tool industry and so on) shipbuilding has to be seen as a vital economic prop. Thus, the current “rearming” program is a buildup primarily in conventional weapons and parts designed to counter the”capitalist threat” of a strike by capital, i.e., a refusal to reinvest capital in the U.S. unless the rate of profit is satisfactory.

Manufacturing the Soviet Threat

In the aftermath of widespread exposure to the depraved depths of U.S. foreign policy revealed during the U.S. war with Vietnam a general revulsion to and intolerance for U.S. militarism known as the “Vietnam Syndrome” swept the nation. Policymakers were forced to react to massive anti-militarism sentiment, i.e., in the mid 1970’s, for example, 72% of the respondents to a Harris public opinion survey felt that the government was spending too much on defense. In the new era of detente the U.S. space program languished while military expenditures expressed as a percentage of the Gross National Product fell to pre-1950 levels. Many prematurely suggested that the U.S. had left militarism permanently behind and that other ways besides militarism would be found to forge a national consensus and solidify foreign policy. Since orthodox economists have long denied the links between the prosperity generated by the U.S. economy after WWII and the always sizable and sometimes growing (in terms of general business slowdown) military expenditures, these economists gave no attention to the economic consequences of reduced military spending.6

For an exceedingly brief period of time during the Vietnam period, a portion of U.S. militarism had been demystified for millions of U.S. citizens. The demystification, of course, was limited to a clear realization that U.S. government policy in Vietnam had no legitimacy. Unfortunately, critics of the war effort did not probe the taproot of militarism—the link between corporate needs and military waste. They failed to do this, first, because virtually no orthodox economists have been willing to subject the economic role of militarism to critical analysis, and second, because U.S. militarism wrapped in the veil of the Soviet Threat, has been discussed only by experts ordained by the State to carry-on such an analysis-i.e., the various defense industry associations, Pentagon planners, think-tank specialists, Sovietologists, State Department planners and members of the National Security Council.

Demystifying U.S. militarism starts with a correct understanding of the magnitude of military spending, because the taproot of militarism is economic not ideological. Military expenditures in the U.S. are usually twice as important to the economy as they appear in the government statistics. This is so because government figures merely account for those military contracts that must be paid in any given year. Alternatively, these budget figures for “National Defense ignore the important economic impact of contracts as they are issued to corporations. Only two, three, four or more years after the contract has been let does the Pentagon issue payment to the contracting corporation. Since the military “shopping cart” is weighted-down with long-term contracts (such as shipbuilding at the moment) there is serious underreporting of the economic impact of military spending. Only several years later, when the GNP is higher, will these contracts be paid—although their economic impact has been felt long ago.

Moreover, the government’s manner of reporting military expenditures (expressed as “National Defense” as a percent of GNP) draws attention away from the fact that 6.4 million U.S. workers are employed by the military either in uniform, as civilians, as military plant workers or as reserves. (In addition, perhaps as many as 825,000 workers are engaged in the $15 billion arms export market.) Nor is there any tendency to note that military related research employs roughly one-third of all scientists and research engineers and absorbs two-thirds of all research funds allocated by the federal government. Likewise in a new era of resource scarcity no stress is put on the fact that the military is the eighth largest user of petroleum products (in terms of nation-state rankings) and consumes more than the entire populace of India.

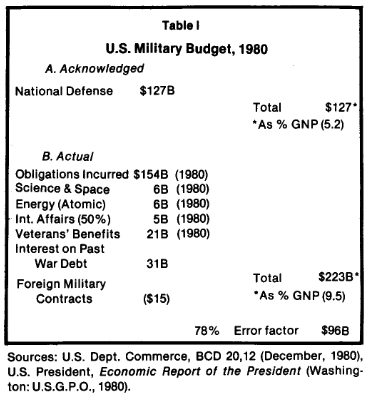

But this is not all. The impact of U.S. militarism is disguised by the failure to mention the following military-related outlays: Veterans’ Benefits, Space Expenditures, The Department of Energy’s budget—most of which goes for the cost of operating military reactors and making three nuclear warheads per day, International Affairs (50% at least being military) and interest on past wars (50% total interest payments). As can be seen from Table I below, in FY 1980, for example, the official figures showed that “National Defense” costs came to $127 billion-a “mere” 5% of GNP. Properly accounted for in terms of obligations incurred by the Pentagon, i.e., the actual value of contracts and other related costs, total outlays came to $223 billion. This is an error factor of 78%. (Adding in foreign arms contracts brings the error factor to 90%.)

Yet, even this is not the major component of mystification in militarism. The major component is the belief that the trillions of dollars spent since 1950 have been devoted to defending the U.S. and its allies. In fact, no specialists seem to be willing to attribute more than 25% of military expenditures to defense (i.e., strategic weapons) however defined. Notice that the above discussion of the arms buildup of 1979 and 1980 had virtually nothing to do with nuclear deterrence. Rather, the present arms buildup is devoted to conventional weapons for the most part—to buoy profits and perhaps to fight in the Third World. As to strategic defense, economist David Calleo’s study of the Department of Defense Annual Report, 1980 shows that 15% of the budget goes for “Strategic Forces”, the remainder being allocated to conventional outlays.7

Yet, even this is not the major component of mystification in militarism. The major component is the belief that the trillions of dollars spent since 1950 have been devoted to defending the U.S. and its allies. In fact, no specialists seem to be willing to attribute more than 25% of military expenditures to defense (i.e., strategic weapons) however defined. Notice that the above discussion of the arms buildup of 1979 and 1980 had virtually nothing to do with nuclear deterrence. Rather, the present arms buildup is devoted to conventional weapons for the most part—to buoy profits and perhaps to fight in the Third World. As to strategic defense, economist David Calleo’s study of the Department of Defense Annual Report, 1980 shows that 15% of the budget goes for “Strategic Forces”, the remainder being allocated to conventional outlays.7

Nonetheless, President Reagan in a speech on February 18, 1981, gravely announced that the U.S.S.R. had outspent the U.S. on arms by $300 billion since 1970. While pledging to “get the government off the backs of the American people”, Reagan was, in fact, employing the Soviet bogey to shift the impact of government spending away from labor-intensive social programs toward capital-intensive, high profit military contracts.

The curious genesis of the $300 billion figure is worthy of further investigation. In the aftermath of the U.S. defeat in Vietnam the “Vietnam Syndrome” resulted in a shift in U.S. foreign policy toward detente and unofficial alliances with regional despots such as the Shah of Iran in order to maintain U.S. hegemony without directly incurring the costs. The weaknesses of this program alarmed elite policy planners who were determined that profits would be maintained at home while capital would flow freely abroad via the old system based in U.S. hegemony and U.S. militarism. These policy planners, many of whom had been “present at the creation” and had participated in the forming and writing of the earlier mentioned NSC-68, challenged the Ford and Carter administrations’ drift towards multipolarity and compromise in world affairs. In 1974 as the impact of U.S. policy in Vietnam became obvious, the bipartisan policy planning elite that had determined the direction of U.S. foreign policy (thereby empowering the U.S. State with considerable autonomy to juggle the level of military spending to fit the overall needs of the economic system) found itself unable to control policy. Initially this group sought to recement policy through then Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger who was pushing to drop detente. However, Schlesinger’s intransigence resulted in his firing in November, 1975, and in the decision by this group of policy planners (including Paul Nitze and Leon Keyserling, the two principle authors of NSC-68) to again form a powerful elite group known as the Committee on the Present Danger (CPD).

Although the history of the CPD is too complex to recount here, this group was successful in driving then President Ford into a reassessment of the National Intelligence Estimate (NIE). The NIE is normally conducted by the Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board which draws on CIA data to determine the level and direction of Soviet arms outlays. The NIE has a great deal to do with the level of military expenditures requested by the executive branch from the Congress. The CPD charged that the NIE estimate of Soviet arms was too low and that there should be an “independent” analysis. Ford eventually concurred and a seven member panel comprised of four CPO members (Nitze, Foy Kohler, William Van Cleave and Richard Pipes) generated the now famous Team B report. Since the CPD’s formative documents show that the objective of the group was to convince policymakers that “the principle threat to our nation … is the Soviet drive to dominance based upon an unparalleled military buildup” it is hardly surprising that the Team B report “discovered” a sizeable error in previous CIA estimates of Soviet outlays—i.e. the U.S.S.R. was spending 11-13% of its GNP, not 8% on arms. Multiplying this “error factor” times 10 (for the 10 year period 1970-80) Reagan’s advisors came up with the uncontested figure of $300 billion, which he claimed monetized the degree to which the Soviets had outspent the U.S.

Thus, for 1980 the Team B’s method suggested that the Soviets were spending roughly $164 billion, while the U.S. was spending “merely” $127 billion. Although the attempt to monetize two separate military forces across two disparate cultures and economic systems is extremely complex, essentially all NIE estimates itemize Soviet forces and then calculate how much it would cost to duplicate these forces in U.S. prices. Although innocuous appearing on the surface, this method is fraught with danger, because no attempt is made to measure qualitative differences. When adjustment is made for the differing quality of troops, the differing efficiency of weapons, and the fact that the U.S. has weapons that the Soviets do not, it is possible to make a very crude military comparison. Such an exercise, which cannot be conducted here, suggests that the inferiority of Soviet troops (in relation to U.S. training and weapons used), the lower efficiency of Soviet weapons and the fact that the Soviets lack some 30% of the technologies that the U.S. utilizes, makes it possible to estimate in dollars a range of Soviet outlays of from $73 to $133 billion for 1980. The figure which seems most consistent with published knowledge of Soviet capabilities for 1980 is $84 billion.8 Or, alternatively, U.S. outlays at $160 billion (obligations incurred + space) are almost 200% greater than Soviet expenditures!

In 1976, with the Team B report and the combined power of the prestigious 140 members of the CPO behind them, the CPO attempted to sway President-elect Carter to stack his military policy planning appointments toward the CPD’s recommendations. Failing in that endeavor the CPO set-out to divert the Carter administration from their detente-global interdependence-human rights course. In this they were successful. By late 1977 or early 1978 President Carter had moved from his campaign pledge to reduce military spending every year, to increasing it. Furthermore, Carter in late 1977 or early 1978 issued a classified document known as Presidential Decision-18 (PD-18). PD-18 argued that the U.S. could define the Middle East as part of its “vital interest”, and that the U.S. was willing to go to war with the U.S.S.R. or its allies to maintain the status quo in that region. This memorandum also outlined the concept of and need for a Rapid Deployment Force.9

PD-18 followed quite closely upon a meeting President Carter had with seven members of the CPO, a group referred to as the CPO “power structure” by the CPD’s director. Pressured by the CPO and unable to prolong the tepid business expansion which started in 1977, past 1979, Carter began a sustained buildup in military expenditures in July of 1979. Thus long before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Carter had moved considerably over to the CPD’s position. By December 1979 (two weeks before the Afghanistan crisis) Carter revealed comprehensive long-term plans for a major military buildup to the influential Business Council at the White House. By early 1980 with his National Security Advisor wildly proclaiming that the Afghanistan crisis was “the gravest threat to world peace since WWII” Carter proclaimed PD-59, the Carter Doctrine.

Although Carter had moved from elected dove to self-proclaimed Cold Warrior in late 1978, his actions were not sufficient to satisfy the CPO. At the outset of his campaign, Ronald Reagan was advised on military matters by Team B and CPO member Richard Van Cleave and CPO member Richard Allen. In the aftermath of his election Reagan selected Allen as his National Security Advisor, (a position often considered to be the most powerful in the executive branch of the government aside from that of President). Other CPO members in the Reagan Administration include: Team B member Richard Pipes on the staff of the National Security Council, Eugene Rostow, head U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, Jean Kirkpatrick, U.S. Ambassador to the U.N., William Casey, Director C.I.A., and Ernest Lefever, nominated Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights. In short, the CPO and, indirectly, Paul Nitze, are making U.S. military policy.

The Contradictions in the Rearming America Policy

Paul Nitze and his cohorts in the CPO are riveted on a strategy of maintaining U.S. hegemony, regardless of the economic consequences. The irony is that while they are serious about the “Soviet Threat” and may well be searching for “offensive forces to attack the enemy”, to the U.S. corporations that provide the tools of trade to the Pentagon the name of the game is profit not performance. The current military buildup, like earlier ones, reveals that policy planners such as Nitze have had their greatest success only when, as in the 1948-50 and the 1978-80 period, the sluggishness of the economy and the lack of any national plan by the business community leads to the blending of strategic Cold War considerations with the bolstering of profit margins for business. The results have always tended to be either scandalous, laughable or pathetic, depending on one’s perspective. Whether it be WWI, WWII, the high Cold War years or the present buildup, U.S. corporations have always used the military buildup to raise their profit margins by whatever means possible.

Thus, in WWI, a scandal broke when it was learned that U.S. steel corporations had sold thin substandard steel to the Navy for its ships. A recent parallel case is that of the multibillion dollar Trident submarine program, where the Navy has accused General Dynamics (the number one military contracting firm) of placing faulty steel in as many as 126,000 separate locations in the first Trident sub, the Ohio (which will cost over $1.2 billion). Similar malfeasance has been found in another shipbuilding case with Litton Industries (the sixth ranked contractor) accused of billing some of its losses on commercial work to the Navy via a complex scheme of accounting subterfuge spread over an eight year period.

All of this, however, seems mild in comparison with the findings of defense analyst Franklin Spinney, a civilian in the Department of Defense’s Programs Analysis and Evaluation Division. The startling conclusion of the well-documented Spinney Report is that the more complex weapons systems become, the less likely they are to be operational. Spinney points out that modern fighter planes are so complex that some operate only 350fo of the time. (Earlier planes were operational 60-66% of the time.) Worse yet, each new “improved” plane is much more costly than the last and less capable of meeting its proscribed efficiency standards.10 Spinney’s report continues a rather long and dismal tradition demonstrating that the military establishment has been bamboozled by the military contracting corporations. Actually, given the structure of the military market—i.e., that the companies involved basically control the high-profit marketing process, such results make sense.

Militarism and the Productivity Crisis

Increasingly inefficient weapons do not, however, make sense in a stagnating, inflating economy caught in a productivity crisis. The shift toward conventional weapons on the one hand, and toward aerospace exotica on the other, is sure to push the U.S. economy deeper into the quagmire of stagflation. In the 1940s and 1950s a host of new technologies that either lowered costs or created demand for new products were “spun-off” from military research. Examples would include the revolution in petrochemical products, the jet engine, the computer and the modern electronics industry. Since the late 1960s when the space program underwrote the basic technology for the microelectronic revolution, military spinoffs have been minimal both in relation to the amounts spent on military research and development and in relation to the economy as a whole. Presently, there is no reason to expect sizeable spinoffs from either the conventional weapons or exotica, because R & D now concentrates on highly exotic products with little marketable potential.

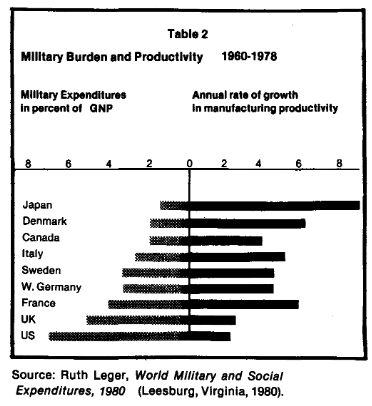

The current buildup, then, promises to (1) inflate profits, (2) increase incomes for the twelve or more million workers whose jobs are sustained, directly and indirectly by military spending, (3) push up prices even higher as these workers try to buy goods from firms schooled in the art of pass-through pricing, (4) raise prices on military products thereby raising further the demands by the CPO to raise military expenditures, (5) make foreign manufactured goods even cheaper as U.S. corporations neglect even further their industrial base to pursue easy military profits, (6) thereby leading to balance of payments crises as the inflation draws-in cheaper imports, (7) absorb even more research scientists and scientific funding thereby lowering civilian technological advances below what might be achieved. (Table II below illuminates this final point.)

Furthermore, as the mix of government spending is shifted from social services to military outlays the employment effect of government spending goes down. That is, military spending is capital-intensive, social spending is labor-intensive.11 Thus, Paul Nitze and the CPD will manage to make a poor situation worse for millions of people while raising profit margins for a few and buoying up the GNP figure by raising the level of unproductive expenditures within it.

Furthermore, as the mix of government spending is shifted from social services to military outlays the employment effect of government spending goes down. That is, military spending is capital-intensive, social spending is labor-intensive.11 Thus, Paul Nitze and the CPD will manage to make a poor situation worse for millions of people while raising profit margins for a few and buoying up the GNP figure by raising the level of unproductive expenditures within it.

Simply put, the 1950s are not the 1980s and the U.S. economy can no longer afford the burden of the hegemonial power. What was learned in 1950 has to be unlearned in the 1980s. Unlike the 1950s, the U.S. must compete in a internationalized economic setting where its closest competitors equal or more often exceed the U.S. in technological capabilities. In the 1950s the U.S. could withstand the inflationary effects of military spending. Today such inflation will lead to rising imports, declining exports and a declining dollar. Drawing research scientists and engineers into military work will insure that the U.S. economy falls further behind its competitors, thereby raising the unemployment rate and deepening the productivity crisis. Yet the dismal tendency to go back to the policies of NSC-68 rather than forward to some type of humane economic planning lends great weight to the notion that when history repeats itself it does so the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.

—

James M. Cypher is professor of economics at California State University at Fresno. He has written several articles on military spending, the capitalist state and the international economy.

REFERENCES

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 4<<

- Paul Nitze, “Strategy in the Decade of the 1980s,” Foreign Affairs 59, I (Fall, 1980), p. 92.

- See: Jerry Sanders, “Shaping the Cold War Consensus,” Berkeley Journal of Sociology XXV (1980) 67-136.

- Walter Mossberg, “Army Thwarts Tank Threat Posed by Chr:xsler’s Problems” Wall Street Journal 2/18/1981.

- Assuring Increased Spending for Arms,” Wall Street Journal, 11/6/1980. “Defense Issues” would include iron and steel production, ordnance, shipbuilding, engines and turbines as well as electronics and aerospace. aerospace.

- Wall Street Journal, 1/28/1981 and 1/14/1981.

- See James M. Cypher, “Capitalist Planning and Military Expenditures” Review of Radical Political Economics, VI, 3 (Fall, 1974) 1-19.

- David Calleo, “Inflation and American Power,” Foreign Affairs, 59,4 (Spring, 1981), p. 806.

- This is a complex calculation that cannot be detailed here. For some background see: Franklin D. Holzman, “Is There a Soviet-U.S. Military Spending Gap?” Challenge (Sept./Oct. 1980) and Center for Defense Information, Soviet Geopolitical Momentum: Myth or Menace?” The Defense Monitor (January, 1980).

- Louis Kraar, “Yes, the Administration Does Have a Defense Policy” Fortune (June 18, 1978).

- Franklin Spinney, “Defense Facts of Life” Programs Analysis and Evaluation Division Staff Paper, DOD (December 5, 1980).

- Shifting the mix will result in 14,000 to 30,000 jobs lost per billion dollars shifted, or 420,000 to 900,000 due to President Reagan’s projected shifts in FY 1982. See Marion Anderson, The Empty Pork Barrel (Lansing, Michigan: PIRGIM, 1978) p. 2.