This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Taking Back the Land

by Jim Gallese & Maura Mullen

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 2, March-April 1981, p. 5 — 10

Arthur J. Gallese has lived and studied in postrevolutionary Nicaragua. Maura Mullen is a free-lance writer active in the Central American solidarity movement in Boston.

The Nicaraguan people won their political independence on July 19, 1979. Following the overthrow of Somoza, the Sandinistas began transforming the impoverished and repressed society into one where the principal goal is the establishment of equity for all. Since the victory, the country has been enmeshed in a difficult struggle to gain its economic independence. The Sandinistas feel the revolution must be consolidated, advanced, and defended. As Jaime Wheelock, Minister of Agricultural Development explains, the

. . .people, led by their vanguard, did not rise up just to topple a tyrant. The heroic Nicaraguan people rose to arms for the resolution of a serious social and economic crisis. This crisis must be resolved. . .by all the people, for we aren’t satisfied with just the overthrow of Somoza’s regime!1

The new leaders are acutely aware of the poverty of the nation, and of the structural limitations impeding change. The Frente Sandinista Liberation National (FSLN), with only a few thousand trained cadre, was able to lead a people’s army, but after the victory had neither an extensive organizational base nor the technical and administrative personnel needed to manage the economy. A “class alliance” which was formed with the bourgeoisie indicates a mature response to the challenges of socialist transformation, rather than, as some writers have suggested, a petty bourgeois or social democratic mentality within the FSLN. The Sandinistas are, for the time being, allowing the private sector to develop the forces of production. A truly mixed economy has resulted in which there exist both state and private enterprises. The state will exert considerable control over many aspects of both production and distribution. Socialist transformation in Nicaragua will be popular, democratic, and gradual, directed towards maximizing the social well-being of the dispossessed and acknowledging Nicaragua’s objective social and economic realities.

This article will first provide a discussion of the conditions in Nicaragua following the revolution. The steps taken to reconstruct the economy, particularly those relevant to the agricultural sector, will be outlined, and we will then describe the current structure and performance of this sector.

The Legacy of Somoza

The political and economic conditions in Nicaragua today cannot be thoroughly examined without taking into consideration the disastrous legacy left by the Somoza regime. The FSLN inherited an impoverished economy ravaged by war destruction and structurally unsound. The Nicaraguan people had voted with their blood (40,000 dead, 100,000 wounded) for the new revolutionary government and were united behind the Sandinistas as they began to face the difficult period of national reconstruction. High rates of inflation and unemployment, a bankrupt financial system (carrying an external debt of $1.6 billion) were several of the more frightening spectres haunting the new government.

Seventy percent of the country’s main export crop, cotton, was lost, left unplanted during the war. Corn, bean, and rice fields were also unplanted. At the same time, a major sugar refinery was damaged just as the cane was ready to be processed. The war had also interrupted blight control in the coffee fields. This destruction was all the more serious in light of the structural deformities in the economy. Dependent upon the world capitalist market for the sale of its crops, the nation’s economy had been totally geared towards providing raw materials to industrialized countries, especially the United States. Both agricultural and industrial sectors experienced irrational and uncoordinated growth patterns, some of which are outlined below:

- The land was concentrated and controlled by the agro-export bourgeoisie.

- Virtually no internal market existed, nearly all production being oriented to the exterior.

- Expensive imports, needed to modernize and make the export sector competitive, consumed nearly all foreign exchange, aggravating the balance of payments deficit.

- All food for domestic consumption was produced in a second, backward sector. The land area of this sector dwindled as it was encroached upon by the export sector, resulting in a reliance upon imports to feed the population.

- The rural people served as both producers of the food consumed and as a reserve labor force in the export market plantations.

The Sandinista leadership believing the agrarian reform to be the best way to overcome these structural problems, implemented a bold new economic policy for national reconstruction. Legislation and action commenced soon after the July 1979 victory. First, they confiscated all of Somoza’s property (agricultural and commercial) as well as the property of some of his supporters. This property now constitutes the A.P.P., or Area of People’s Property. Twenty five percent of the 8.8 million acres of cultivated land has been transferred to the authorities of the agrarian reform. These farms can provide about 20% of production. The remaining cultivated areas remain in the hands of the private sector, composed of both large landowners and small-medium producers. Overall, the private sector contributes 80% to total agricultural production. The entire agricultural economy provides about three quarters of Nicaragua’s exports and, directly or indirectly, employs 70% of the labor force.2

The processing and marketing of the main exports, cotton, coffee, sugar, and beef, had been carried out by a few large-scale firms. Some of these, formerly the property of Somoza, were brought into the A.P.P. More importantly, export trade in agricultural products and much of the internal trade in foodstuffs are now directed by the state. The industrial and commercial enterprises that once added to the immense wealth of Somoza now form part of the base being constructed for public control of the economy, and contribute to the consolidation of the revolution.

The bourgeoisie is being “encircled” by such moves, and its financial hold on the economy has been further eroded by nationalization of the banking system and insurance companies. Credit and foreign trade controls are powerful tools in the hands of central planners. Mass organizations such as the Rural Workers Union (A.T.C.), the Women’s Association, Civil Defense Committees, and the Sandinista Worker’s Confederation can assist planners by voicing the concerns of the people. These mass organizations also play a vital role due to their efforts to encourage and develop class unity. The ATC is a leading participant in agricultural development and its functions will be outlined in detail in a following section.

Structure of the Agrarian Economy

According to Jaime Wheelock, Minister of Agricultural Development, the overall policy of the reforms is to extract state income from the very large private holdings via taxes, support the medium size landowners, and reform the tiny landholding sector.3The so-called “postage stamp” pattern, or parcelization of land, is considered to be destructive. Avoiding the disastrous experiences of the Mexican land reform, the expropriated farms were not subdivided and given to landless peasants. Rural workers are now employed on both private and state farms, and their standard of living has risen.

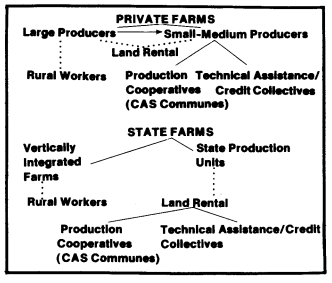

The Sandinista Agrarian Communes, CAS, and the technical assistance/credit cooperatives are two new organizational forms which are transforming the relations of production in the countryside. (see Table 1) Small to medium producers are encouraged to pool their resources and work the land collectively in a CAS; however most are now organized in credit/ service cooperatives and continue to farm individual plots. On the large state-owned farms which do not include industrial or processing facilities, land is rented to the peasants. Similarly, they voluntarily choose between forming communes or cooperatives.

The experiences of the Reyes family (a composite) can help illuminate some aspects of rural life in Nicaragua Libre. Arturo is one of the over 100,000 minifundistas (small landowners) in Nicaragua who grows basic grains for domestic consumption. Small producers such as Arturo generally own anywhere from 0- 10 acres, and have an annual income of under $150. The size of Arturo’s farm is less than average and he also rents land. The income it generates did not permit his two oldest children, Marian Elena and Jorge, to return home following their participation in the Sandinista revolution. Maria Elena, now 20, took part in the literacy campaign in the countryside until August, 1980. Since then she has been helping organize a commune in the state sector. Jorge married a woman who lived near the small plot of land farmed by his family. The couple now work part-time on a private cotton producing plantation, whose owner rents some land to Arturo.

Reactivation of the economy is heavily dependent on the private sector and much of the recovery will be a function of the government’s success in stimulating small producers. Historically, minifundistas have been forced to rent or sharecrop a portion of their land. Before the reform, Arturo had to give nearly half of his harvest to the neighboring latifundista (large landowner) for the “privilege” of using his land. The Sandinistas have established a cash-economy throughout the countryside, thereby eliminating sharecropping arrangements. Moreover, rents have been slashed under FSLN leadership. Arturo now pays only about $3.50 an acre for his land, about one-tenth of the historical level.

Arturo and a group of fellow workers have formed a cooperative which makes them eligible for low-interest credit and technical assistance from the PROCAMPO division of the National Agrarian Reform Institute, INRA. With the credit allotted to them they have begun improving their land, utilizing new agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilizers. They receive advice from PROCAMPO technicians before carrying out such improvement. In the past, poverty forced all the cooperative members to work as seasonal, salaried laborers in the cotton fields of the latifundista. Today only half the group needs to supplement their income in this way. This increased self-sufficiency of the small farmer has led to labor shortages on some large private farms. As a result, the FSLN leaders have been studying ways to solve this problem.

The people of Arturo’s region were staunch supporters of the Sandinistas long before the 1979 victory. They joined the Committee of Agricultural Workers, a precursor of the ATC in 1976 when the Sandinistas worked clandestinely in the countryside. The ATC has over 100,000 members and is growing. The agricultural workers union is a vital link between government planning centers and peasants. While it works closely with the government, it is an independent organization and not a political appendage. The ATC has proven this by voicing opposition to some government policies and influencing changes made. When Arturo and his fellow workers began to discuss forming a cooperative, they contacted their regional ATC office. A representative assisted in organizing 20 families into what the Sandinistas call a “precooperative” and then contacted INRA/PROCAMPO in order to proceed with the process of organizing a full-fledged technical assistance/credit cooperative.

The people of Arturo’s cooperative do not feel they fully understand how the communes are operated, and are not ready to form one. The credit and technical assistance cooperatives are considered to be a preliminary stage in the formation of production cooperatives or communes. Some 17,000 farmers have organized TA/credit cooperatives and received about half of total agricultural credit. Under Somoza, nearly all such credit was given to large farmers growing export crops. Arturo and others also benefit from nationalized marketing channels, under which the government directly purchases basic grains from them, which are sold at subsidized prices in the cities.

Arturo’s daughter exemplifies the new Nicaraguan woman and the growing revolutionary consciousness of the nation’s youth. She and other guerilla fighters who emerged victorious in 1979 are working to defend the freedom they fought so hard for. Maria Elena came to her commune after a period of working on the Literacy Campaign. She had left her father’s farm at the age of 14 to study on a scholarship in a colegio, or high school, in Managua. While studying, she became active in the mass women’s organization known as AMPRONAC. Originally focussing on the problems of urban women AMPRONAC expanded its scope to include rural women during the revolution and changed its name to AMNLAE. AMNLAE continues its support of the Literacy Campaign, which ended its first phase in August, by building “mini-libraries” and working with the evening radio programs broadcast for people wishing to reinforce their newly acquired skills. Maria Elena helps teach a discussion and study group formed on her commune. She feels strongly about the efforts of popular organizations like the ATC and AMNLAE to aid in the political education of her people and agrees that production cooperatives are the best solution to the problem of economically irrational land parcelization.

Her CAS was formed by a group of landless rural workers who rented underutilized land on a state farm. Small individual gardens are permitted, but the majority of the land is farmed collectively. The profits of the commune are distributed among four funds: 1) a communal health, education, and housing fund, 2) a capital improvement account, 3) an emergency fund, and 4) a wage fund. Each worker is paid from this last fund according to the amount of labor performed. The commune is run by a coordinating council, members of which are elected by a general assembly of all workers. The coordinating council is in charge of planning and political affairs and members chosen from this council compose an administrative committee which handles the day-to-day functioning of the commune. All members participate in decisions regarding production schedules, crop allocation, and purchases of capital equipment. This particular commune was organized on land expropriated from Somoza. These lands have been subdivided and are administered by the workers with the guidance of INRA staff.

The other organizational form developed from expropriated estates is the vertically integrated enterprise, which usually produces crops such as cotton, coffee, sugar or livestock for export. State cane plantations are located near the state sugar refineries, for example. They were maintained intact to avoid losing the positive effect of economies of scale. These units are under the direct administration of INRA. Similar operations are found in cotton, beef and coffee enterprises. State farms operate on a profit/accounting basis, like commercial enterprises. They are administered by an INRA appointed manager. Credit is obtained from the nationalized banking system, and interest on all loans must be paid. Some profits from export crops are re-invested in the enterprise. On an increasing number of state enterprises food crops are grown after cash crops have been harvested. This reflects a Sandinista policy aimed at reaching self-sufficiency in food crop production in a very short time. Democratic and decentralized methods of decision making are increasingly being employed on the state farms. This is a long, difficult process and many obstacles have been encountered. Such efforts, however, indicate that the Sandinistas envision not only a rational economic reorganization but a significant change in productive relations as well.

Large Private Sector

Reflecting the extreme concentration of land ownership which developed under the Somoza dynasty, there are about 600 very large land holdings (over 2,000 acres) in Nicaragua. About half of these were expropriated from Somoza and his friends. Cotton production, centered on the large latifundios, is the most significant activity within the private sector, accounting for over a third of all exports. In 1980, however, the harvest fell to only 20% of historic levels because the war broke out at the time planting was to have occurred in 1979.

Jorge Reyes and his new wife still work as wage laborers on one of these large cotton plantations. Last year, many workers mistakenly believed that the revolution would spare them from having to perform the back breaking labor of cotton picking. This caused severe labor shortages, even though the size of the harvest was much smaller than normal. This year the state lands and the fields of the small-medium cotton growers were planted to capacity. The large bourgeois landowners were less eager to plant. On Jorge’s plantation, the landowner only planted his best lands, where his investment was sure to bring a high return. He seemed reluctant to maintain his farm equipment and was suspected of funneling profits out of the country (decapitalization), rather than reinvesting them in his farm. This is illegal in present-day Nicaragua, as is letting good land lie fallow. To combat this problem, the ATC trained Jorge, his wife, and other agricultural workers to monitor the landowners and to spot decapitalization, hoarding, and violations of the labor code on their farms. Throughout Nicaragua idle fields have been invaded by landless peasants and the state must decide whether they are to be returned or remain in the hands of the peasants.

Workers on the private farms benefit from legislation granting better pay, improved living conditions for seasonal workers and social security. Moreover, all Nicaraguans benefit from free medical care which is becoming increasingly available in rural areas.

The Ministry of Agricultural Development provides devices to stimulate export crop production, such as credit availability, and sets prices for products in a range approved by private sector representatives. Most commercial farmers and cattle ranchers belong to associations which are grouped together as the Nicaraguan Agricultural Producers Union, which forms part of COSEP, the Nicaraguan “Chamber of Commerce”. COSEP promotes the interests of the private sector and has a seat in the State Council, a principal legislative body.

The political and economic importance of small producers like Arturo Reyes has not been lost upon the large private producers, and they try to compete with ATC for their support by forming private producers’ unions. In Matagalpa, for example, large producers contrived to gain such support and organized some 90% of the area’s small producers into a cooperative controlled by the large farmers by offering credit services. However, thanks to the ATC, this ploy was uncovered and many of the small producers left to form their own cooperative.

Such contradictions plainly illustrate that class struggle has not ended in Nicaragua. The class alliance is becoming weak as the people organize and the FSLN constructs an economy in the interest of the majority. Large private producers feel increasingly threatened and have even organized counter-revolutionary schemes. In the words of a leading member of the FSLN, “There are two historic projects in conflict, one that wants to forge a new society that ends exploitation, the other that wants to reintegrate elements of the old social order into a society based on class privilege.”4

Analysis of Agricultural Performance

The first year of the land reform was a success due to the ability of INRA to maintain a balance between the interests of the state sector, rural workers and peasants, and the large commercial farmers and ranchers. (see Table 2) Nearly a quarter of the agricultural economy has been socialized through the formation of state farms and production cooperatives. State marketing channels provide stable and fair prices to both producers and consumers. The needed institutional framework for further research, planning and administration is under construction.

Although increased production is vital to improving conditions in Nicaragua, there is also a “social wage”, which is an important component of the ‘new social and political policy. The literacy campaign, expansion of health and education services and the numerous technical assistance and credit services now provided to the population have benefits which will pay off in greater production and social well-being in the future.

Nonetheless, problems of low productivity, labor, shortages, and income maldistribution persist. Productivity declined when workers were given hourly wages as opposed to the old piecework system. Political consciousness is still quite low among most workers, but is being combatted by the ATC and other groups using education campaigns. Both production and productivity must increase, however, if the economy is to expand and diversify. The ambitious social program of the Sandinistas requires that such surplus accrue to the state and not to individual workers. Large wage increases would be inflationary and benefit no one, but after years of living in dire poverty it is not easy to convince the Nicaraguan people that austerity is necessary. In the long run the Sandinistas know they must diversify the economy and escape from the dependent agro-export oriented economy they inherited from Somoza. A long slow process of diversification, economic planning, and political mobilization has begun.

Other trading partners must be found. Appropriate technology industries must be developed. At the same time, the forces of reaction within Nicaragua are aligning with forces of reaction in the capitalist centers in order to prevent the realization of the Sandinista program. Many believe that U.S. intervention in El Salvador will become regionalized. Some fear that U.S. imperialism may even invade Nicaragua in order to prevent the development of the kind of society which will show to the rest of Central America that revolutionary change is the only answer to the region’s massive social and political inadequacies.

AGRICULTURAL PERFORMANCE VALUE OF SELECTED EXPORTS*

*(figures rounded off) $U.S. millions 96.9% of production goals met in these crops In 1978-79, 970,000 manzanas (manzana: about 2.5 acres) were planted. In 1980, 960,000 manzanas were planted. Source: Barricada, December 17, 1980 |

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 2 <<

REFERENCES

- Jaime Wheelock, speech on November, 1980.

- Burbach, R. and T. Draimin, “Nicaragua’s Revolution.” NACLA’s Report on the Americas, May/June, 1980, p. 14. Gallese, A. “Progress and Problems in the Nicaraguan Agrarian Reforms: One Year After the Revolution” Presented to the American Sociological Association, August, 1980.

- Simon, L. “After the Revolution. An Interview with Jaime Wheelock.” Food Monitor. July/August, 1980, p. 10.

- Interview with Orlando Nunez, of INRA, NACLA, May/June, 1980, p. 8.