This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Star Wars: Mirrors of Reality

by Christopher Jennings

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 6, November-December 1980, p. 27–29

Christopher Jennings is a freelance science writer living in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is science editor for Living Alternatives. He is interested in issues concerning energy, environment and technology.

The success of Star Wars and its sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, lies in their accurate reflection of the attitudes and concerns of our society. The film’s cinematic imagery depicts the pressing issues and trends of our time, lending form to our fears and doubts. Protagonists strive and conquer where the viewer cannot; frustrations are released through vicarious action and pyrotechnics.

The dramatic screenplay, at the outset of Star Wars, strikes a chord of empathy within us. The movie opens with a shot of a space vehicle pursued by a gargantuan battlecruiser. The audience immediately identifies with the rebellious protagonists, who are struggling against a totalitarian bureaucracy. This scene shows the forms of technology used by the heroes compared with that used by the villains. Here, George Lucas, the producer of Star Wars, contrasts our own society’s conflicting expectations of science and technology.

The Empire is a symbolic spectre of the fears that technology will be used to subjugate humanity. It is represented by large, awesome and intricate technological structures. The Death Star exemplifies the ultimate dream of mankind — the achievement of planet-destroying technology. A cancerous cell capable of killing all living cells, its destruction is cosmically just.

Human societies within the Empire resemble insect civilizations; rigid in strata and specialization. The Empire’s warriors are little more than clone-like lackeys, practically tripping over one another in order to get shot up by the manly rebel heroes. Individuality is obscured by their battlegear, and they elicit no pity from the audience as they fall like bowling pins. Even the Empire’s higher echelons are not exempt from this expendability. In The Empire Strikes Back. Darth Vader disposes of a couple of commanding admirals for their failure to capture Han Solo’s ship.

Only Darth Vader is portrayed as unique and non-expendable. In Star Wars, his cold robotic manner and total lack of compassion or even anger, casts doubts on his humanity. Is he a super robot or some fusion of man and machine? Whichever, he elicits both fear and fascination. Evil, he is still the ultimate, analytical bossman, one we hate, but whose efficiency we might admire. The Empire could represent the final conglomeration of corporations, an inexorable machine consuming its human components and spitting them out. If so, then Darth Vader is one of those mystical corporate, demi-god managers, who runs corporations by parameters of efficiency regardless of the consequences. Vader’s visage is altered slightly in The Empire Strikes Back. One suggestive scene hints that Vader, though humanoid, has been grotesquely changed by his power.

The Empire is also the Government. Our disillusionment with the present U.S. Administration, and several past ones, finds an outlet through the actions of the rebels. Parallels between the Empire and the Government are very strong, as both creep into personal affairs.

The movies raise strong doubts about whether the government or the corporations are in charge; many people see both as incompetent, disinterested, self-serving, and sometimes evil.

Rebels appeal to audiences raised on American folklore and mythology. In our culture, the individual rules supreme, the lone warrior is the agent of justice. The rebels’ technology is cast in this mold. Small familiar looking spacecraft allow individual action and volition; smallness also presents an illusion of technical simplicity. The X-wing fighters incorporate technology straight out of Vietnam aerial bombing. Strapped into the cockpit along with the pilot, the audience enjoys the movie’s cheap thrills: speed, exhilaration, the sense of danger, and aesthetic pyrotechnic displays of death. In one moment we cringe from the technological spectre of the Empire, and in the next, we exalt in the momentary fulfillment of our desires for a faster phallic symbol.

Yet, placed amidst this technological circus are downright trite characters. Colloquialisms run rampant throughout the film. When Hans Solo boasts, “I’ve added some special modifications myself!” about his spaceship, the Millennium Falcon, he might have been talking about his ’55 Chevy. There is little doubt that the colloquial aspect of Star Wars adds to its popularity, but it is disappointing that the filmmaker made no attempt to imagine a different kind of society that could coexist with advanced technology.

The film presents instead, a fantastical confrontation of our own society’s social forces. The plot of Star Wars is veiled by the shoot-em-up action, but the rebels are fighting to restore the free Republic, whose authority was usurped by Vader and the Empire. Luke Skywalker’s father was a member of the Jedi knights, an aristocratic order of the Republic, so his longed for victory over the Empire would enable him to claim his heritage. Skywalker’s victory over the Empire would bring back the good ol’ days, when any goodhearted, hard-working person could attain power and prestige in the free universe. People in the audience, feeling paralyzed by the specialization of this society and the “impingement” of its government, wish they could do the same.

Prevalent in Star Wars, is the theme of mysticism and morality versus technology. With the development of test tube babies and genetic engineering, people are questioning the shaky moralistic foundations of our technologically oriented civilization. The legitimacy of science as a religion is under attack. People are looking for answers, and organizations such as churches or cults are swelling their ranks. When the going gets rough, it is good to have God (or a secular counterpart) on your side. Lucas intentionally made the Force a non-personified, but omnipresent power. The notion of the Force recognizes and prods the search for a personal WATS line connecting to “All That Is.”

The Force is a Judea-Christian concept. Like everything touched by Christian ideals, it is cleft in half: good on one side, bad on the other. On an individual level our conscience sits perched on one shoulder, personified as an angel, while the devil whispers into our other ear. This leads to a constant conflict between two or more voices within our heads. Enveloping our well-meaning, but naive, hero is an aura of Calvinism. Luke Skywalker exemplifies the belief that humans are supreme, inherently able and knowledgable: and that one human can make all the difference — if he/she merely overcomes his/her mortality and allows the divine to blossom within. In Star Wars, the Force does little else but to allow Luke to shoot straight with his electronic eyes shut. The concept of the Force does not include self-actualization (except if one wants to climb the social ladder), nor communications with the universe. The calm presence of mind displayed by Luke’s mentors, Ben Obiwaan Kenobi and Yoda, derives from supreme confidence in their ability to manipulate their environment, not from acceptance of peace with the divine plan or with nature.

In summary, Star Wars portrays the schizoid character of our Judeo-Christian technocracy: while humans desire and strive towards power incarnate, we also seek solace, or protection from an outside force.

This attitude is expressed in another popular and recent film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind. In this film, it is the space brothers, in their loving and technological wisdom, that come to save humanity from itself.

Star Wars does represent a change in the mode of thinking of filmmakers. It is a science fiction revival in mainstream media reincarnated as science fantasy. Earlier science fiction (in the 1950’s) concentrated on visualizing quasi-feasible scientific, technological or sociological trends. Its creators were, in fact, overly concerned with the legitimacy of their futuristic imagery. Science fiction writers believed that any proposed device or trend had to have some foundation. Thus, factory robots were combined with artificial minds to create awesome machines: and V-2 rockets became, through the power of imagination, star-traversing spaceships. In a similar manner, science fiction writers overcame the limitations of time and space with abstract concepts existing only in the minds of physicists and mathematicians. The belief that with a screwdriver and a little ingenuity, humankind could accomplish anything was intrinsic in their stories.

In contrast, science fantasy, Star Wars, takes technology and energy resources for granted. In The Empire Strikes Back, Luke’s small X-wing fighter, obviously a limited-range fighter in concept, easily travels from one solar system to another. Spaceships such as the Empire’s behemoths are not even hindered by size. Yet the source of energy is of little concern.

Hollywood has done it again: profitably marketed the same old human conflicts, good versus evil spiced with the eternal love triangle, this time neatly packaged in a unique space box.

Hollywood’s progression from John Wayne to Flash Gordon to Star Wars shows a clear lack of emotional, intellectual or creative development, despite the advances in cinematic technology. This is a dangerous pattern because science fiction/fantasy expresses and influences the expectations people have of science — and the aims of scientists as well. The Foundation Trilogy, one of Isaac Asimov’s early writings (1951), is an excellent example of this. In it, Asimov extrapolated the rhetoric of his fellow scientists during the birth of the nuclear power industry. His scenario of the future contained atom-powered spaceships, automobiles, and even a walnut-sized nuclear reactor which fit into a belt buckle. People utilized the inexhaustible resources of the universe. Asimov’s writing was in tune with that era. America was in an economic boom: the New West and all of its opportunities were open to the adventurous: spaceflight was possible and Americans believed in unlimited expansion. A whole generation was raised on these unreal expectations of the future.

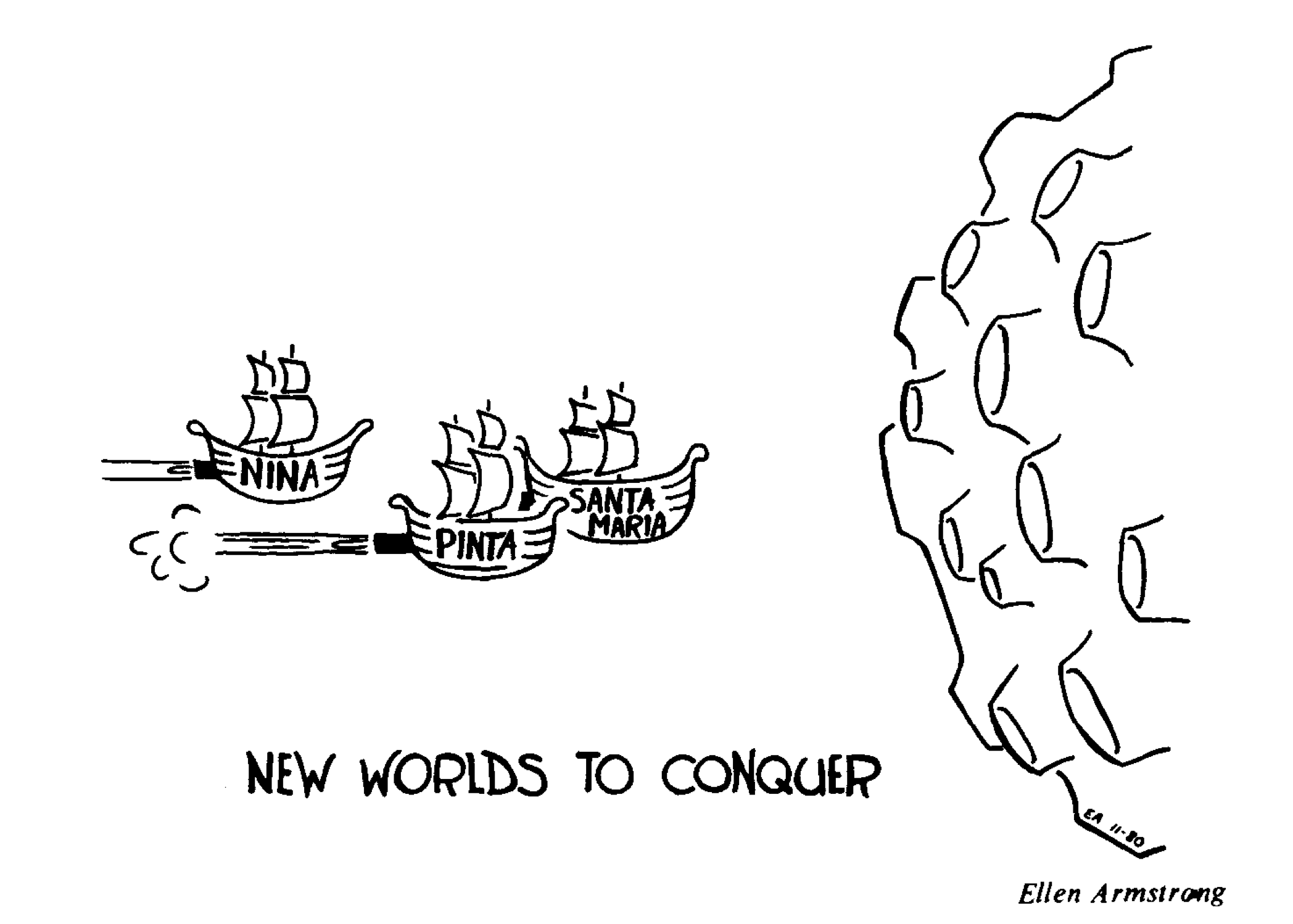

Although Star Wars is set “A long, long time ago … far, far away”, its implications are clear: people have the ability to overcome physical limitations, enabling them to escape their environment. Thus, the movies are devoid of any sense of ecology: demonstrated by intergalactic spaceships obliviously dumping garbage (and heaven knows what else) into space. The same attitude has been rife in American culture since the first white people landed on this continent: “Let us burn up the resources here, dump the garbage, and then go someplace else.”

The Star Wars series may be one of the last visual indulgences of this style of thinking. For we, as a society, are being confronted with our limitations. We feel the pinch of depleting resources and the occurrence of events like Three Mile Island and Love Canal have made some people realize that since we will be on this planet for a long time to come we cannot destroy it. For the recession-burdened consumer who is tired of the thought-stimulating entertainment of the sixties and seventies, relief is spelled S-T-A-R W-A-R-S. It is an escapist fantasy.