This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Plant Patenting: Sowing the Seeds of Destruction

by Cary Fowler

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 5, September-October 1980, p. 8-10

This article is reprinted from Coevolution Quarterly. Winter 1979/1980. Cary Fowler is director of the Resource Center at the National Share Croppers Fund’s Frank Porter Graham Center. Since 1937, the National Sharecroppers Fund has worked with and tried to advance the best interests of the nation’s sharecroppers.

American agriculture is imported. All major food crops grown in North America originated elsewhere, in what we call the Third World. For Americans there is really no such thing as the home-grown meal. Wheat, spinach and apples, for example, are from Asia. Soybeans come from China. Corn and tomatoes originated in Central America. Potatoes are from the Andes and sorghum originated in Africa. Only hops, Jerusalem artichokes, sunflowers, a couple of berries and a few other minor foods originated in North America.

Nearly all of our food crops are of ancient origin. Thousands of years ago our Stone Age ancestors began domesticating plants, saving the best seed for replanting the next year. Human efforts and natural selection processes resulted in different varieties of food crops becoming adapted to “different niches in the ecosystem.” The result was thousands of varieties of wheat, rice, corn and other crops as genetically distinct as beagles and great danes. In diversity there was strength. As pests and diseases changed or mounted more powerful attacks, plants evolved different or better defenses. These defenses were represented in the genetically diverse varieties of each crop. Modern agriculture is changing this natural system.

With the breeding and marketing of new “improved” varieties, traditional varieties are being replaced. Farmers and gardeners stop growing them. Field after field is planted with one variety. Where thousands of varieties of wheat once grew, only a few can now be seen. When these traditional plant varieties are lost, their unique genetic material is lost forever. If, because of genetic limitations which result from inbreeding, new varieties are no longer resistant to certain insects or diseases (conceivably even insects or diseases never before known to attack wheat), then real catastrophe could strike. Without existing seeds which carry specific genes conferring resistance it may not be possible to breed resistance back into wheat, corn, or any other crop.

How serious is the situation? The National Academy of Sciences warns us that “most crops are impressively uniform genetically and impressively vulnerable.” Respected scientists speak of agriculture’s questionable future. Others talk of the “collapse of civilizations” that would accompany another major genetic-related crop disaster like the Irish potato famine. These fears are not far-fetched. Perhaps the most endangered of our crops according to the National Academy of Sciences, is wheat, the dietary foundation of millions of people. What will happen when the genetic material needed to confer resistance has vanished with a plant variety now extinct?

Seeds As Big Business

Recently a rush of mergers and corporate takeovers has hit the seed industry, creating much cause for alarm. Old, family-owned seed businesses have been, and are being, bought up by large multinational chemical and drug firms – the same companies that manufacture pesticides and fertilizers. Purex now owns Ferry-Morse, Sandoz (a Swiss chemical and drug conglomerate) owns Northrup-King, and ITT has just purchased Burpee. In addition, Celanese, Ciba-Geigy, Monsanto, Shell, Pfizer, Union Carbide and Upjohn have all recently bought seed companies.

Will these big corporations encourage their new seed company subsidiaries to develop plant varieties that require more or fewer pesticides and fertilizers? The answer seems clear. Already many of the companies listed above have begun to develop and patent processes to coat seeds with herbicides and pesticides, thus using seeds as a delivery system for chemicals into the field. With this development, the link is forged between the marketing of seeds and agricultural chemicals (see box).

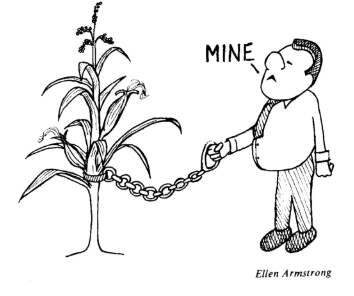

As seeds have become big business, pressure has been put on governments around the world to insure high profits for the seed industry. Many governments have passed laws allowing companies to patent new varieties of plants, in effect to patent life.

Plant patenting laws, however, benefit only those companies big enough to hire teams of researchers todevelop new varieties. Since the passage of such laws in the United States, the government has granted 73 patents on beans. Over three-quarters of these patents are held by just four corporations: Purex, Sandoz, Union Carbide and Upjohn. Armed with the monopoly provided by patents, these large corporations can confidently jack up prices. Meanwhile, smaller seed companies are forced to specialize in a dwindling number of unpatented varieties.

A Rose Is A Rose Is A Rose?

Plant patenting laws were first instituted in Europe in the early 1960s at the urging of French rose breeders. What is the European experience with these laws? In Europe, enforcement has proven to be a legal jungle. It is almost impossible to prove in court that your “tomato is genetically identical to my patented variety.” In order to prevent confusion with patented varieties, the Common Market countries have simply outlawed many unpatented plants. European governments are establishing a “Common Catalog,” which lists all varieties that are legal to grow. Each month varieties are deleted from the list. Sometimes over a hundred are scratched out in a single month. These deleted varieties cannot be raised or sold by seed companies. Even backyard gardeners cannot grow the illegal varieties if their gardens are located close to a commercial plot using a patented variety. With such restrictions – and a fine in England of up to £400 for violators – many varieties are quickly falling out of use.

Dr. Erna Bennett of the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome estimates that by 1991, fully three-quarters of all the vegetable varieties now grown in Europe will be extinct due to the attempt to enforce patenting laws.

In England, the Director of the National Vegetable Research Centre has called the laws a “self-inflicted injury.” Environmental organizations are asking Canadian groups to take and safeguard seeds of the newly outlawed varieties – ironically just as the Canadian government is attempting to establish its own patenting scheme. And OXFAM, the charity whose projects are generally located in the Third World, is considering the allocation of funds to help preserve Eurpoe’s endangered vegetable varieties. Truly, Europe is no longer safe for vegetables.

This could happen in the United States. In 1970 Congress passed a law deceptively entitled, Plant Variety Protection Act, establishing a plant patenting system in the U.S. We have yet to experience the full effect of this legislation. Breeding programs undertaken after 1970 generally have not had time to produce patentable varieties. But bills (H.R. 999 and S. 23) are pending in Congress to amend our plant patenting laws to include six previously exempt vegetables: tomatoes, carrots, celery, peppers, cucumbers and okra. The passage of these amendments will pave the way for the U.S. to join the European-dominated international organization that promotes and coordinates plant patenting laws. Most of the nations belonging to this organization have found it necessary to outlaw many vegetable varieties in a desperate attempt to enforce their plant patents. For the privilege of joining this select group, the initial membership fee will cost U.S. taxpayers nearly $100,000.

RECENT SEED COMPANY TAKOVERS

|

Seeds of Life

The future of agriculture depends on the genetic diversity in food crops that our ancestors created over the 10,000 year history of agriculture. This future is being threatened by laws that require genetic uniformity and a reduction in the number of varieties allowed to exist. Without genetic diversity, agriculture loses its primary defense against pests and diseases, thus creating absolute dependency on pesticides. Conveniently, the same companies that profit from plant patenting stand by ready to supply the “needed” agricultural chemicals. Agriculture also loses much of its ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions. Meanwhile, human cultures daily lose varieties they have come to value for their taste and nutritional qualities.

If diversity is to be preserved and agriculture’s future insured, we must make whatever effort it requires to stop plant patenting laws. We must take steps to establish plant preserves to protect endangered varieties of food crops and their wild relatives. And we must expand seed collection and storage programs.

As we engage in these public activities, we can begin to address the problem in our own backyards. We can grow and help preserve some of the old varieties. We can educate people about their importance.

But in the end, the future of agriculture can be insured only by healthy, vibrant small farms. The old varieties are threatened today, not because they taste bad or are nutritionally deficient, but because they do not suit the requirements of the factory farmers, the food processing industry and the big seed companies. The California plantation owner who grows tomatoes to be shipped all over the country cannot grow the old, tasty varieties. Their skins are not tough enough. Their insides are not hard. If the old varieties are to flourish, they must be, as they always have been, grown by small farmers and sold to a local market. This system of agriculture has provided sustenance to people for many centuries. It is an enduring agriculture that we tamper with only at great risk.

For thousands of years our ancestors toiled to develop the rich diversity that characterizes our agricultural system -the diversity a permanent agriculture requires. The challenge we face is how to preserve this lifegiving legacy.

LEGISLATIONPlant “patenting” has been available in the U.S. since the Plant Patent Act of 1930. The Act is part of Title 35 of the U.S. Code, and is run by the Patent Office. The catch is that patents apply only to asexually produced plants (or to plants that reproduce both sexually – seeds – and asexually – rhizomes, grafting, etc.). You can see examples in any fruit tree catalogue; patented varieties will have their Plant Patent number right below their name. Protection for sexually produced plants had to await the Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970. This is administered by an office in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and instead of patents, they issue Certificates of Plant Variety Protection. It’s interesting to note that the Agriculture Department opposed this act when it was first proposed during the Johnson administration, but then reversed itself and supported it in 1970. So the Act appears to be another contribution by former Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz to the betterment of corporate America, for it was the protection afforded by this Act which made seed companies become attractive acquisitions for multinational conglomerates, as the preceding chart shows. When all of this was happening in 1970, Heinz and Campbells, the two big soup producers, argued successfully for the exclusion of six vegetables from the protection of the Act. They were afraid protection would result in higher-priced seeds. Apparently it hasn’t, at least for them, for they have since withdrawn their objections. H.R. 999 and S. 23 amend the 1970 Act to include the six vegetables – tomatoes, carrots, peppers, celery, okra and cucumbers. They also change the length of protection from 17 to 18 years. Both these changes are necessary before the U.S. can join UPOV (Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants), the European seed patenting clearinghouse. -Richard Nilsen Editor, Co-Evolution Quarterly |

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 5 <<