This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Factory Workers of ZhuZhou: A Photoessay

by Nancy Edwards

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 11, No. 5, September/October 1979, p. 18–26

To China! — A City Neighborhood in Zhuzhou, Hunan

A fine, light rain has fallen, still caught and held by fan-shaped leaves of the gingko trees along the avenue. There is an earthy smell in the air. The day started cooly enough, but warmed-up quite suddenly so that by ten o’clock I already feel that little pool of sweat forming in the small of my back, reminding me that another summer, another cycle in life had come.

A little girl comes walking down this dusty street. She must be about four years old. Her heavy black hair is bound back in braids; like many adults crowding along the street with her, she wears plastic sandals on her feet. Bordering each side of the street are three-story apartment buildings, their casement windows thrown open to catch any stray breezes. Bamboo poles jut out overhead, bearing items of family laundry — blue pants, white shirts, pastel blouses and the occasional splash of a red garment or a brightly-colored piece of bed linen.

At the intersection where this little side-street meets the boulevard is the Pork Store. The girl reaches the corner and becomes engulfed in a sidewalk crowd surrounding an older woman selling “ice suckers” (vanilla-bean flavor today) from a fancy big thermos. At the curb, four gray state cars with white side-curtains are a sure sign to all that our foreign delegation is nearby. The sidewalk crowd swells, the more curious moving over the threshold and into the store with us.

It is cooler in here, and dim; the pungent smell of smoked pork fills the air, and bottles of beer, wine and Mao-tai sparkle in rows behind a glassed enclosure. Clerks, weighing the pork and wrapping packages, stand in back of the counters, their fingers clicking across the abacus’s beads calculating bills, making change. The average consumption of pork is one jin (1/2 kilo) per person per week. The price is set at the provincial level, determined by local conditions, and the prices in China have been stable for nearly 20 years.

The walls of the store are shiny white tile, hung with signs, price listings, and brightly-colored, locally-made wall hangings of dyed pigskin, depicting nature scenes. In the back is a little restaurant, and comrades sit at tables lunching together. A man carrying a string bag of groceries, a furled umbrella and bamboo fan — completely prepared for the June climate — stops to rest a moment and chat with friends.

Next to the Pork Store is the vegetable and poultry market. Its produce is colorful and nicely displayed: rosy brown eggs are piled one on top of the other to form perfect little pyramids, the light from the window glistening across their shells. Overhead signs and pictures give mini-lessons in diet and nutrition. The Chinese are busy people, and the busiest time here is between 5:30 and 8 a.m. But I suspect this was always so, for this was traditionally a market town.

Market Town to Industrial Center

Today Zhuzhou is an industrial city, with an urban population of 205,000, or 803,000 if one includes the surrounding countryside. Town and country nestle in the gently arching curve of the Xiang Jiang River, whose waters flow into the Yangtze and onward to the coastal plain meeting the East China Sea at Shanghai. Zhuzhou has always been a small provincial market center — long before Liberation, before Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai and the Red Army, before Chiang Kai-shek and the Guomindung marched across the land, even before Sun Yatsen and the New Democracy. Local peasants pushed their porkers on two-wheeled handcarts, as they do now in the early morning, toward Zhuzhou to market and to the tannery.

Around the beginning of the century, Zhuzhou became an important stop on the Guangzhou (Canton)- Wuhan railway line, and began to acquire prominence as the Pingxiang coal mines were connected to Zhuchou by rail. A small industrial proletariat began to emerge from the townspeople, from the peasantry.

Today the factory workers of Zhuzhou are important manufacturers of railway equipment, of locomotives, and of rolling stock. Copper and zinc are mined nearby and form a part of the city’s industrial development, as do the chemical and fertilizer industries. There is a sizeable glass factory, and hemp is transformed into fine cloth at a local textile mill. And of course, there is the leatherworks — where the hides of local pigs are transformed into fine coverings for human hands and bodies.

Politics and Production: The Leatherworks and a Hemp Factory

In 1956 industry here began to develop, and in 1958, during the Great Leap Forward, the leatherwork factory emerged with 54 workers and 150,000 yuan1 in production funds. Now, twenty years later, this industry employs 341 workers, and its production funds total about 2.5 million yuan. Since 1965, the workers have produced leather goods for export.

As in many factories, workers’ wages range from 38 to 80 yuan per month depending on seniority, with 50 yuan the average. The length of the working day extends from 8:00 in the morning to 5:30p.m., with an hour and a half for lunch, six days a week. Eighty percent of the workers are women, our host tells us, “because it’s light work.”2

In one workshop, perhaps a hundred women sit on backless benches, stitching leather gloves on sewing machines brought here from Shanghai. The centers of the tables are piled high with glove pieces, looking nearly like soft yellow petals from exotic flowers. The windows are open; it is an airy and uncrowded workshop. Next to each worker’s machine is an enameled cup with a lid, to keep heat from escaping the pale yellow tea. From time to time, a woman takes a sip or stands up and reaches for something on the table.

A hundred or so sheets of red paper with large written characters form a colorful bulletin board along the back wall. “What’s this on the wall? A production record?” Comrade Wong, an interpreter, tells me this is the “Determination of the Workers” board. “You see, after the workers study the political documents, the articles, they write their own feelings of determination. Because after smashing the Gang of Four, they are determined to do the work better than ever before.”

I ask her to read one: “Just pick one, read one.” She consults one of the factory cadre3 and then leads the way to the bulletin board. We select one from a row near the bottom. Yellow characters on the red cover give the name of the worker, and the title “Determination Article.” Underneath this coversheet is a white piece of paper, with the following statement:

Under the correct guidance of the Central Committee, I must follow Chairman Hua closely and continue to criticize the Gang of Four and, in order to realize the four modernizations designated in the People’s National Congress, which was also designated by Premier Zhou, I specifically made a determination, a plan:

- I must read books of Marxism-Leninism with painstaking effort, to raise my political consciousness.

- To take part in the movement of criticizing the Gang of Four actively, and to raise my class struggle consciousness.

- Unite with other workers and help each other to do the production work actively.

- I must strive to finish my tasks before the year has ended.

It would be a mistake to treat such a document as only a rhetorical exercise. Political intensity and undertone are not to be underestimated in the context of China’s industrial workplace, where the dispute between the leftist Gang of Four and the Deng Xiaoping factions of the Party took on special significance.

Deng’s concern with technological modernization took a number of forms, including a focus on educational ideologies and standards which affected the training of technical and scientific workers, an emphasis on the importance of expertise in the management of factories, and a renewed emphasis on techniques for increased production. Various political views, including those of the Gang of Four, held that these ideas represented a conservative bourgeois political line. The concept of workers’ management championed by the Gang of Four is now subject to heavy official criticism for advocating practices which would ultimately have weakened and divided the masses. Its ultra-leftism is now seen by the Deng Xiaoping faction as a disguise for an essentially bourgeois line.

Again and again, cadre in various factories in Zhuzhou as well as in Shanghai emphasized that the abandonment of work rules during the Gang of Four period resulted in sabotage to production, and thus in sabotage to the national welfare. The Gang of Four faction accused Zhuzhou’s Railroad Boxcar Factory of operating under the “theory of productive forces” — that is, of caring more about production than politics. As a result, during the period of the Cultural Revolution, 90 percent of the workers there, at one time or another went to the countryside to “learn from the peasants.” Apart from the political considerations of such a policy, this practice has accomplished, on a national scale, a considerable economic redeployment of urban labor into agricultural production.

With the Gang of Four-Deng disputes officially resolved for the moment, China’s factories have once again reinstituted work rules. At Zhuzhou’s Hemp Factory, which employs 2,821 workers, productivity is said to have increased three-fold since the period of the Cultural Revolution. A corollary has been the rehabilitation to their old positions of many managerial cadres who were criticized and demoted during the Cultural Revolution. Walking through the various workshops, one notes the omnipresence of “worker emulation boards.” Each workshop has a committee which grades workers on productivity, labor regulation adherence, political study, safety, and so forth. Tokens, such as fountain pens, are awarded to those scoring highest in these ratings, as psychological rather than material incentives to production.

Safety is regulated in the textile mill by cadre who have a consultative relationship with a labor committee of workers. Many phases of textile production are hot, heavy, hard work. Although some workers in the spinning and weaving phases of the process do wear face-masks to protect themselves against inhalation of particles, many others do not. The looms themselves produce deafening noise, but even simple earplugs are not worn. It is particularly disconcerting to see a worker place his or her hands inside a spinning centrifuge, just after the mechanism has been set into motion, in order to more evenly pack and balance the load of hemp.

The Hemp Factory, like the Leatherworks, has a majority of women workers — 61 percent — yet only two out of nine administrative cadre are women; of the technicians, 30-40 percent are women. Often the reason cited for this discrepancy is that time is required to rectify all of the injustices of the old order, and that strides to do so are continually being made.

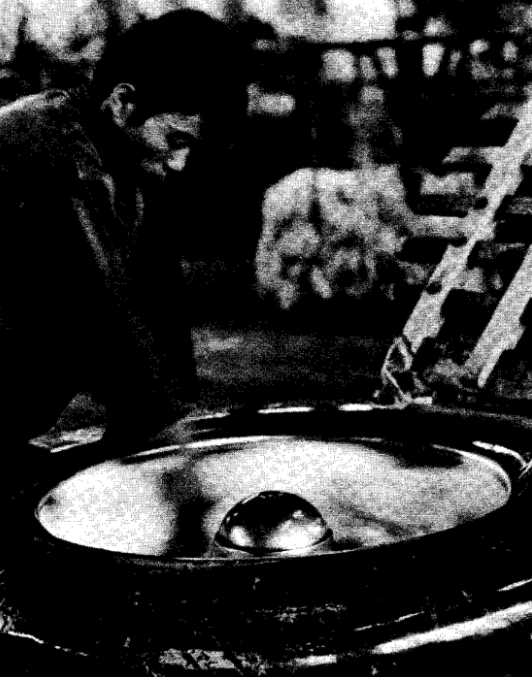

Heavy Industry: Railroad Boxcars

Water and railway connections, together with a proximity to coalfields and sources of other raw materials, have enabled the transformation of Zhuzhou from a market town to an industrial city. The Railroad Boxcar Factory, also built in 1958 during the Great Leap Forward period, employs over 4,000 workers and produces 4,000 cars per year, in thirteen varieties, some of which are exported to Tanzania. Since 1966, the total profit is twice the capital investment, and productivity of labor has increased by 50 percent, largely through technical innovation and continued mechanization.4

The factory complex itself is organized into fourteen separate workshops, and incorporates facilities for the 80 percent of the workforce who live on the site. These include a grammar and middle school, a July 21st University, a workers’ hospital, a nursery, cultural facilities, and living quarters.

The monochromatic scheme of the workshops is punctuated by the presence of the worker emulation boards, which are often quite colorful (lots of red) in their graphic display of work teams’ achievements. Fewer women are employed in this factory than in the leatherwork and textile industries, and those who are tend to be machinists or welders rather than doing casting, stamping, or heavier assembly work. Those working women who are nursing young children have two hours out of the working day — one in the morning and another in the late afternoon — to spend with their infants. Pregnant workers also have additional rest time and lighter work assignments.

Most workers dress in dark blue, and wear soft-crowned hats with narrow visors. Although overhead cranes move materials across the workshops, no one wears hardhats. In like manner, very few workers wear steel-toed shoes, prefering soft cotton cloth shoes or plastic sandals. Safety glasses, while available, are used only by a few, and the general sentiment is that experienced workers have little need for such things. Most assert that they find hats, safety shoes, and glasses uncomfortable. Safety committees exist at both workshop and factory levels, and while self-criticism surrounds these issues, few accidents are claimed.

Factory Workers

Work at this factory is organized into three shifts: 7 a.m. – 3 p.m., 3 p.m. – midnight, and midnight – 7 a.m., with workers rotating weekly among these shifts. No particular effort is made to see that husband and wife work the same shift, and in virtually all cases women as well as their husbands work. Typically, in China workers have one day off per week, and those whose work is at some distance from their families or birthplace have twelve paid leave days (not counting travel time) a year to visit their homes. This is also the case for husbands and wives who have been geographically separated in work assignments. Sick time, with pay, is universal and unlimited in duration.

The factory manager — a 30-year industrial worker, husband, and father of four children — earns 137 yuan a month (compared to 90-108 yuan a non-managerial worker of comparable seniority might earn). Out of this salary, he pays 4 yuan a month for rent and utilities, and saves about 50 yuan. Another somewhat younger man, whose wife is also employed at the plant, claims a combined family income of 127 yuan monthly, of which 2 yuan is spent on rent and utilities. 70 yuan for food, and 30 yuan goes into savings. Savings tend to be used for the purchase of certain consumer goods — such as bicycles, or watches, or are put aside for the occassion of a trip to one’s family home. Young workers, as yet unmarried and still living in parental homes, claim to be able to save nearly half their income. Workers in the Boxcar Factory are also careful to point out that banked savings are regarded as being available for the state’s use in socialist reconstruction and in building the new society, and one gets the feeling that a considerable campaign within political study groups has probably surrounded this topic.

The Boxcar Factory houses a July 21st College which provides two-year vocational and political courses to selected workers, preparing them to acquire theoretical knowledge and skills required to become technicians in the factory. These colleges for industrial workers emanate from Mao’s famous July 21st, 1968 directive calling for a policy of “selecting students from among workers and peasants with practical experience, who should then return to production after a few years’ study.” Science and technology, and applied training are stressed in short courses; the primacy of proletarian politics is a major criterion for admission.

At the Boxcar Factory’s July 21st College, most worker-students are lower-middle school graduates. Beneath classroom portraits of Mao, Hua, Lenin and Stalin, they study mathematics, tolerance, electricity, and heat treatment. They spend about 3-4 hours a day in the classroom, over a two year period. During this time, they receive their usual wage, although they do no productive labor. While they will probably not receive an increase in salary after graduation, they nevertheless will return to positions in the factory that entail greater mental engagement and stimulation than most workers are likely to find in the highly routine repetitive tasks of production.

At noon in the factory compound, workers chat among themselves as they break from the demands of production and move with clusters of friends along the roadway joining the various workshops to the worker’s lunchroom building. There, sunlight spills through tall windows into the large dining-anteroom. Wooden tables and benches are arranged along either side of an open central space, and everyone crowds in lines leading to small pass-through windows where food is served by women kitchen helpers. Eight or ten different meat and vegetable dishes are prepared each day. Above the windows, signs post the daily menu and price listing alongside the portraits of Chairmen Hua and Mao. For a few cents one can buy a heaping portion of delicious spinach in hot garlic oil, or plates of pork and mushrooms together with bowls of hot rice and fancy twisted steamed bread — all of which contend most favorably with the cuisine in the foreign visitor’s dining room at the plush, Peijing (Peking) Hotel.

Many vegetables served by this kitchen are grown in gardens on the factory grounds, which provide lovely patches of green and tilled earth between the shops and foundaries. If they wish, workers may eat three meals a day here for about 15- 18 yuan a month. Many buy only lunch, but others often eat breakfast here as well. The kitchen staff attempt to meet special dietary needs, and monitoring of the menu is based largely on the demonstrated popularity of various dishes. While workers quickly fill the available indoor tables, others take chopsticks and bowls and sit in little groups outside in the shade.

Watching these people eating, resting, talking, one is struck by the absolute absurdity of propaganda that conjures forth the image of “faceless masses.” The experiences of even a few days among them forever replaces that fiction with the very real flesh-and-blood picture of a sincere and vigorous people. Yes, there is little doubt that China’s modernization has a long way to go, but there is also no doubt that these people have already brought it very far indeed

Nancy Edwards is an anthropologist who has done research in Central and South America, has taught in colleges and universities in the Midwest and East, and is presently involved in social research in science education at New York University’s Medical Center. She was a member of Science for the People’s second trip to China in summer 1978.

>> Back to Vol. 11, No. 5<<

Notes

- A yuan is worth about $.40.

- Judy the official note taker did not record whether this was said by a man or woman. *The cadres are those persons who hold positions of special responsibility in the various organizational levels of Chinese economic, political, and social life. Generally they are Party members. The Chinese term previously used for ‘officials’ was dropped because of its negative historical associations.

- The cadres are those persons who hold positions of special responsibility in the various organizational levels of Chinese economic, political, and social life. Generally they are Party members. The Chinese term previously used for ‘officials’ was dropped because of its negative historical associations.

- The factory manager stated that they realized 2,100 technical innovations in the 1966-78 period, of which 200 are regarded as significant. Further, they report that the factory’s half-year goal is finished a month ahead of schedule.