This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

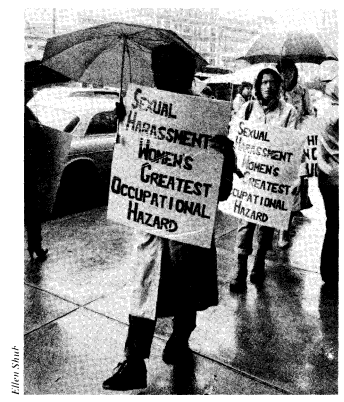

Sexual Harassment: Your Body or Your Job

by John Beckwith & Barbara Beckwith

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 4, July-August 1980, p. 5-7 & 35

Barbara and Jon Beckwith are longtime members of the Boston chapter of SftP. Barbara teaches at an alternative public high school. Jon teaches and researches microbiology, and is currently active in the Boston sociobiology group.

At workshop sessions at the conference (of women miners), the participants’ unanimous complaint was that they were victims of sexual harassment. Many said they were repeatedly subjected to physical assault and verbal provocation… Some told about “company men” from foremen to mine superintendents, who made propositions after refusing to act on their complaints of sexual harassment, including repeated incidents of male exposure in the isolated mine tunnels.1

“If you don’t cooperate sexually, you don’t get the mounts — it’s that simple.” (Donna Hillman, ex-jockey).2

“I hadn’t been teaching that long when the dean of my college was all over me for sex. He was terribly insistent and I repeatedly refused. The next thing I know he suspended me from teaching…” “Yes, I won (reinstatement), but it was after an interminable battle and that bastard jeopardized my whole career.”3

Rape. Wife-beating. Incest. Pornography. Over the last five years these issues of violence against women have been raised by the political activities of women’s groups. However, until recently there has been little interest in an even more pervasive form of violence against women, a form which, in addition, has severe economic consequences: sexual harassment of women on the job.

The scope of sexual harassment is staggering. It ranges from propositions and sexual innuendo to rape. It is just as pervasive in universities as in blue collar jobs, in police forces as in acting schools, in the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission as in unions The Women’s Legal Defense Fund estimates that “more than 70% of working women experience sexual harassment on the job.”4 Other surveys have come up with similar figures.5,6

The Economic Consequences of Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment contributes to women’s inferior status in the job market. Frequently women are forced to choose between sexual harassment and lack of advancement, low pay, or job loss. Many women will quit their jobs rather than submit to the advances of their superiors. In January 1973 employed women averaged 2.8 years of continuous service with the same employer, while men averaged 4.6 years. Lin Farley, in Sexual Shakedown, attributes a significant fraction of this turnover to sexual harassment. Job turnover results in loss of seniority, on-the-job training opportunities, promotions and raises, involvement in unions, insurance eligibility, and strong recommendations. Women who stay on at their jobs without responding to male advances can be confronted with a powerful array of penalties: demotions; reassignments of shifts, hours, or location of work; refusal of overtime; impossible performance standards; and negative job evaluations.

In addition, the strain of both the original harassment and the penalties for non-compliance can have severe physical and mental effects on women. These range from minor pain and tics to major illness, physical damage in the case of rape, or nervous breakdowns.7 Even without physical damage, many women experience a loss of self-respect which makes them more vulnerable to male domination in future jobs.

“I never spoke to the police, that I was ashamed to do, thinking it must be my own fault in some way.”8

“I felt humiliated, incompetent. I was unable to do my job.”9

As in most other aspects of the employment scene, blacks have suffered more than whites.

Of all women, they (black women) are the most vulnerable to sexual harassment, both because of the image of black women as the most sexually accessible and because they are most economically at risk.10

However, black women have taken a leadership position on this issue, having brought a disproportionately large number of the law suits. Because sexual exploitation has been integral to racist oppression in this country, black women are less likely than white women to view sexual harassment as a personal problem.

Our male-dominated society encourages (often to the point of requiring) women to present themselves as sexual objects in order to get certain jobs, and rationalizes male sexual aggression against them as expressions of men’s “naturally” more active sex drive. The courts in some cases still accept this explanation as a defense against sexual harassment charges. In one case, two women were pressured for sexual favors in exchange for employment advancement; the judge found no sex discrimination, stating that the employer’s conduct was “no more than a personal proclivity… By his alleged sexual advances, Mr. Price was satisfying a personal urge… Such highly personalized and subjective conduct is not the concern of the courts.”11 Such judicial rationalizations are not uncommon, even though the work of Masters and Johnson makes it clear that sexual drives are about equally strong in men and women. The explanation for sexual aggression against women on the job clearly lies somewhere other than in “natural male drives.”

Mary Bularzik, in her book Sexual Harassment at the Workplace: Historical Notes, argues that the assertion of power and dominance is more important than sexuality in cases of sexual harassment. Her analysis is similar to the redefinition women have given to the act of rape as primarily an act of violence and domination which cannot be explained in terms of sexual urges. Although sexual acts are involved, they are no more than the means to achieving domination, not the goal itself, as men, including some judges, would prefer to believe.

The Origin of the Problem

A debate often arises in left political analysis when issues of sexism, sex inequality and violence against women are discussed. According to one point of view, these various forms of oppression have their origins in and are maintained by the capitalist system.12 Thus, elimination of capitalism with all its manifestations and the establishment of a socialist society would result in sexual equality and the absence of sexual oppression. An alternative perspective is that the source of these problems lies in patriarchy, a system of men’s domination of women which predates capitalism. This pervasive form of domination exists in all economic systems and in a society such as ours is reinforced by the needs of the capitalist economic system. If one accepts this analysis, then the struggle against capitalism and the struggle against patriarchy must be carried on side by side. We support this latter view as do Lin Farley and Mary Bularzik. Farley sees sexual harassment on the job as part of the way males maintained their control after the emergence of capitalism threatened the base of control formerly found in the family.13 Bularzik believes that women were sexually harrassed even in older socities “to keep them from stepping out of line in other ways.”14

Dealing With The Problem

Until 1975 the term sexual harassment essentially did not exist. While the Supreme Court has not yet ruled on any sexual harassment cases, in 1976 a United States District Court Judge ruled that sexual harassment was a violation of the Title VII sex discrimination clause of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Wisconsin, in 1978, became the first state in the union to pass a statute explicitly prohibiting sexual harassment in employment. In 1979, clerical workers at Boston University, represented by District 65, UAW, won a contract with one of the first sexual harassment clauses in the nation.15 And this year the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission published regulations forbidding sexual harassment on the job.16 Under these regulations employers must pay compensating damages to employees who have been sexually harassed and are liable to court action if they refuse. This progress could not have come about without the actions of women’s groups and the publicity these actions have received.17

However, despite these successes, it is clear that women cannot rely on the courts and the unions as the major source of redress or the solution to the problem. Since the courts are only slowly accepting the idea that sexual harassment is an offense, the likelihood that a court will rule against a case is high. Moreover, legal redress is expensive and time-consuming. With regard to unions, Lin Farley points out:

Unions frequently discriminate against their female members’ needs for equal hiring practices, seniority, equal pay, daycare, maternity leave, social insurance… The mainstream of the American labor movement was fueled at birth by a desire to maintain the male domination of female labor.18

Catherine MacKinnon, in Sexual Harassment of Working Women, also documents union refusal to process grievances based upon claims of sexual harassment, but acknowledges that some unions have supported women. In one case, an auto union actively worked to change the pervasive attitude in a plant that “any woman who works in an auto plant is out for a quick make.”19

Only as women speak out and organize — through support groups in workplaces, assertiveness training, consciousness raising groups, union caucusses, and grass roots women’s worker groups (like 9 to 5 in Boston and Women Office Workers in New York) — will attitudes change and government and unions be forced into action.

Sexual harassment will be stopped when women finally take control of their own labor power via collective bargaining and striking to regain their rights. It will be a long fight but it is the inevitable future. Women’s stamina, energy and courage in the battles on rape and abortion have made recent history; because of sexual harassment, they will change the face of modern work as well. It is only a question of time.20

It is also time that groups, like Science for the People, which have had a longstanding involvement in issues of occupational health and safety and in issues of sexism and sexual oppression deal with the problem of sexual harassment.

Resources

The recent books and pamphlets which we have used as sources in this article are directed at different audiences. Lin Farley’s Sexual Shakedown is the most general book, and gives a readable overview of the problems, with many examples and transcripts of particular cases. We recommend this book strongly since its details and examples cannot help but shock the reader into a recognition of the enormity of the problem. Sexual Harassment at the Workplace: Historical Notes by Mary Bularzik reviews sexual harassment of women on the job since industrialization and even before. Sexual Harassment of Working Women by Catherine MacKinnon is a more technical book which reviews in detail all the major court cases. the approaches that have been used in such cases and the contradictory rulings bv different judges. Fighting Sexual Harassment, An Advocacy Handbook, is published by the Boston-based Alliance. Against Sexual Coercion21, one of the few groups to begin working on this issue. It is a practical handbook for social service workers, written in a down-to-earth style, which outlines both legal and extra-legal tactics for helping clients to fight sexual harassment. Another group which does research on the issue, the Working Women’s Institute, has recently created a National Sexual Harassment Legal Back-up Center (593 Park Ave., New York. N.Y. )

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 4 <<

REFERENCES

- B.A. Franklin, “Female Miners in UMW Meeting Denounce Sexism and Lack of Safety,” New York Times, Nov. 11, 1979.

- L. Farley, Sexual Shakedown (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978), p.61. (Available in paperback. Warner Books, 1979).

- Ibid, p.78.

- “Congress Gets Sexual Harassment Appeal.” New York Times. Oct. 24. 1979. p. C-10.

- B. Stone. “Harassment of Women Workers’ Epidemic,” The Guardian. Jan. 2. 1980, p.5.

- “Most Women in Survey in lllinois Report Sex Harassment at Work.” New York Times. March 9. 1980.

- C.A. MacKinnon, Sexual Harassment of Working Women (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979). p.52.

- M. Bularzik, Sexual Harassment at the Workplace: Historical Notes (New England Free Press, 60 Union Sq., Somerville. MA 02143 — reprinted from Radical America. July/Aug. 1978). p.8.

- L. Farley, Sexual Shakedown. p.22.

- C.A. MacKinnon, p.53.

- Ibid, p.84.

- B. Stone. “Harassment of Women Workers’ Epidemic,” The Guardian. Jan. 2. 1980, p.5.

- L. Farley. Sexual Shakedown. p.28.

- M. Bularzik. p. 16.

- “Contract Bans Sexual Harassment.” Dollars and Sense. Oct. 1979. p.12.

- R. Pear, “Sexual Harassment at Work Outlawed.” New York Times. April 12. 1980. p.1.

- See some of above references and R.A. Zaldivar. “Sexual Harassment — the New Army Issue.” Boston Herald American, Jan. 14. 1980: E. Lesser, “Sexus and Veritas: Yale Sued for Sexual Harassment,” Seven Days. Feb. 23. 1979. p. 25: “Sexual Abuse: Actresses Protest.” The Guardian. Oct. 31. 1979: “Sexual Harassment: Strike Victorious.” The Guardian. Jan. 2. 1980. p. 5: J. Albert. “Tyranny of Sex in the Office.” Equal Times (Boston working women’s newspaper). Aug. 7. 1977. p.6.

- L. Farley. Sexual Shakedown. p. 157.

- C.A. MacKinnon. p. 50.

- L. Farley, Sexual Shakedown. p. 211.

- Available from Alliance Against Sexual Coercion. P.O. Box 1. Cambridge, MA 02139.