This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The Politics of Cancer Research

by John Valentine

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 3, May-June 1980, p. 22-28

John Valentine worked as a medical researcher at Wayne State University in Detroit and recently was a student in the medical Cell and Molecular Biology research program at the University of Michigan. He is now working as the Midwest SftP coordinator.

The doctors said as they took their fees

There is no cure for this disease

— Traditional folk song

Detroit’s new Radiation Oncology Center is a $5 million project within the new Detroit Medical Center, a single massive institution designed to cover most of that region’s health needs. The center will have its own $4 million neutron therapy center for treating cancer, complete with a miniature cyclotron. Such a strategy is reminiscent of curing war with hydrogen bombs. The alternative to dealing with cancer after it has begun is the series of regular warnings from the government to avoid certain cancer-causing chemicals that are around everyone. Only sporadically are some of those chemicals removed from the industrial or retail market. This reinforces the popular emphasis on preventing cancer by controlling diet and “lifestyle.”

The possible courses of action to deal with cancer often conflict. We can exert government control over diet and environment, but these regulations are met with protests about lost jobs, compromised freedom, or impossible enforcement — or with risk assessments stating that the problems are balanced by the benefit to society. Throughout this debate, the results of a huge amount of research seem to have very little certitude. It is almost never heard that “X causes cancer of the Y. So that’s that. Take it off the market.” We almost never hear, either, that “a simple cure is around the corner so don’t worry.”

Why is the question of cancer causation answered by little more than subterfuge and trends? Why is the research so uncertain? Why does prevention seem to be completely a matter of individual choice yet often impossible in spite of individual acts of will? For example, how is it that only recently has asbestos been publicly linked to lung cancer, when the association between asbestos and cancer was so obvious medically by 1918 that insurance companies stopped selling policies to asbestos workers in the U.S. and Canada1?

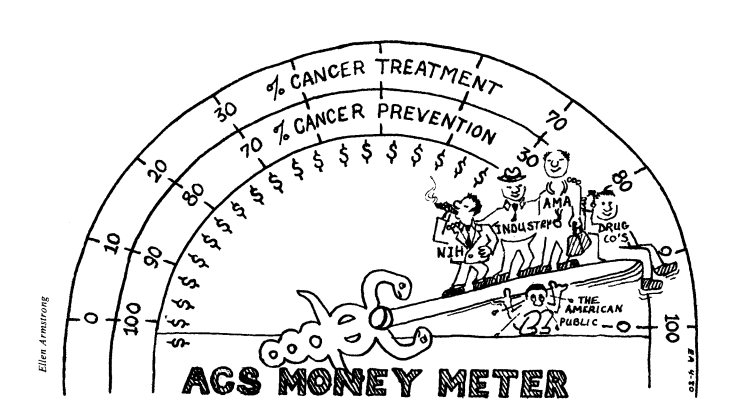

Cancer research in this country has become a bureaucracy and an industry, and certain avenues of research languish because of this. Cancer prevention and its research are not in the interests of the medical establishment, and cause contradictions in our economic system. This article will examine the broad issue of cancer research: it includes analogies to past improvements in public health, a description of research fund distribution, some political analysis, and some discussion of action.

Theories About Cancer

Two theories describe the origin of cancer (carcinogenesis). A viral theory argues that an infectious agent or native ubiquitous viruses trigger cell growth abnormalities. An environmental theory says that cancer is the result of chemical or other alteration (mutation) of the genetic material, DNA. Functioning as a physiological regulator, DNA is constantly active. If several regulatory genes are mutated and no longer contain the information they once did, loss of control over cell growth can occur, says the environmental theory. These are not mutually exclusive theories; variations often include parts of both. It is important to note that though the two theories may be only different approaches to the same process of carcinogenesis, they imply very different courses of action, and research is clearly split between the different approaches.

The Viral Emphasis

The viral theory allows us to view cancer as a communicable disease that attacks the population indiscriminately. It is popular with the medical research establishment. The study of a viral mechanism is amenable to investigation by existing techniques in molecular biology and implies the possibility of a universal vaccine to prevent cancer. However, viruses seem to be implicated in only a few cancers, and even then external environmental triggers seem to have a role in viral carcinogenesis. Also, the cancers (i.e., presumptive viruses) spread in a familial pattern rather than across populations, unlike common infectious diseases. In certain rodent cell cultures viruses will “transform” (make cancerous) the cells. However, Lewis Siminovitch, a pioneer of mammalian cell culture genetics said that, “transforming human cells is difficult. Transforming rodent cells is as easy as falling off of a log!” Most experimentation is done on rodent cells. Another example of research putting the cart before the horse is the observation by Siminovitch that “(practically) 99 percent of the work on humans is done on fibroblasts (a type of cell) and 1 percent on epithelial cells, while the incidence of cancer is 9.9 percent epithelial and 1 percent fibroblastic.” Fibroblasts are studied because they are “easier to work with.” 2

The Environmental Emphasis

The environmental theory or emphasis on cancer engenders public health solutions to cancer. The analogy of cancer prevention to previous reductions of health problems illuminates contradictions in cancer research.

It has been estimated that most of our improved health in the last century is due to improved sanitation and nutrition — public health measures. According to one study, 69 percent of decreased mortality over this period is due to reduction of eleven infectious diseases3. Diseases treated with specific medical measures (such as polio) account for 3 percent of the reduction in mortality. About 97 percent of the reduction is attributed to “standard of living” improvements. The exponential rise in medical costs and treatment began only after 90 percent of the decline in mortality had occurred.

A more specific parallel between cancer and past health improvements is that with antibiotics. The size, shape, cost and limited accessibility of cancer treatment (“cure”) can already be seen by analogy to the administration of antibiotics. The future of cancer treatment would seem to be refinement of techniques, development of drugs and therapeutic compounds, and increasing dependence on a particular industrialized technology, if the chemotherapeutic-surgical approach to treatment and research is further pursued. There is no question that antibiotics are an invaluable tool, but their use is misunderstood. It is unlikely that cancer would be cured in a single simple step by a new “miracle cure,” just as treatment is almost never simple with antibiotics, the old “miracle cure.”

The use of antibiotics in “hard cases” where they are really needed requires screening of the infectious agent to find out to what drugs it might be resistant. That requires the service of the medical-industrial complex. The hospital performs expensive tests; the drug and chemical companies develop drugs, tests, and equipment. Similarly, clinical cancer treatment researchers already predict that it will be necessary to biopsy each tumor and culture it. The laboratory then will have to perform drug resistance tests.

It should be noted that just as antibiotics are invaluable in saving lives, so is cancer treatment. There will always be cancer victims — just as no matter how clean and healthy we are, some people still get infectious diseases. The important question overlooked by this approach is what role and capacity certain strategies have in the total picture of improving society’s health.

It should also be added that an understanding of primary causation (who gets cancer and where) rather than mechanisms of action of environmental agents, has historical precedent. Social study of disease preceded biochemical understanding. For example, good nutrition has an accepted role in good health, even though the functions of many necessary nutrients are still unclear.

Historical precedent and technical arguments make a strong case for a focus by research institutions on environmental studies and the ecology of carcinogens and people, rather than on the viral and molecular process of carcinogenesis. Why has this not occurred? Is it a matter of inertia? A conflict of interests? Economic stakes? A reflection of a particular social and economic system?

Institutions

The institutions that control research and legislation must be examined if an understanding of the politics of cancer research is to be reached. There are institutions that distribute research funds at the national level, such as the governmental National Institute of Health (NIH) and its subordinate National Cancer Institute (NCI), as well as the private American Cancer Society (ACS). At the local level are the universities and private societies such as the Michigan Cancer Foundation (MCF). Both levels should be analyzed.

National Institutions

The NIH provided $2.5 billion out of $6.1 billion spent on cancer research in the U.S. by 1978. Nearly $1 billion went toward cancer research via the NCI 4. Some non-NCI work is related to cancer. These institutions control much of the money, have political power, and virtually regulate the direction of research (by posing the questions and using easily influenced peer groups for review). Yet despite pressure from Congress and the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, “officials at the NIH are skeptical…. It would be better, they say, to tell the public nothing rather than to call for a radical change… that might prove useless”5. This describes an attitude about health in general and about initiating, executing, and acting on research. Is such research funding and public policy a matter of intentionality or are “all the data not yet in?”

Such a philosophy would seem intentional. Alfred Harper, Chairman of the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Science, stated that many epidemic killer diseases in this country are due merely to increased age of the general population6. Senator George McGovern chaired the Senate Select Subcommittee on Nutrition in 1976. In January of 1977, the subcommittee held a press conference to announce a proposal to merely advise Americans about dietary and environmental causes of the “killer diseases.” Because of this, McGovern was shortly thereafter transferred to the Agriculture Committee and his powers as a select committee member were ended7,8.

Sidney Wolf, Director of the Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Health and Science Research concerning the National Cancer Program (NCP). He spoke of the former director of chemical carcinogenesis research at the NCI Fort Dietrich Laboratory. He was, “one of the leading cancer researchers in the country who, without previous notice, lost his job… ” He was replaced by, “a researcher in the area of viral carcinogenesis, and I think this was also demoralizing to people who see this as an ascendency again of an area which has borne far less fruitful results in terms of understanding what causes cancer in humans than chemical carcinogenesis”9.

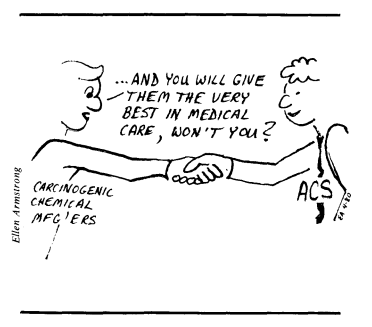

Much NCI money goes to the American Cancer Society, a private foundation which has a powerful influence on NCI and a well funded lobby10. The ACS is a leader of the cancer treatment lobby. In the last decade it has “fought against or withheld support from every single critical piece of legislative action designed to regulate chemical carcinogens in the environment, such as toxic substances legislation, the Clean Air Act, and the Safe Drinking Water Act”11. Also at the NCP hearings it was testified that the ACS has “interlocking relationships with NCI decisionmakers, with industry, and with investment bankers, who are still constraining and distorting policies away from developing higher priorities on cancer prevention activities in the NCI”12. The chairman of the National Cancer Panel of ACS, Benno Schmidt, has made it explicit that he is “rather disinterested in cancer prevention.”

Benjamin Byrd, past president and current cochair-person of ACS, responded at the same session of the NCP hearings by saying that, “Excellent care of cancer patients is more the rule than the exception today,” and “NCI is not a regulatory agency and should not be. Establishment of comprehensive cancer centers (i.e., hospitals) was one of the most important aspects of the National Cancer Act”13. The bias of the NCI reflects a tight association with the ACS. The interlocking between NCI and ACS is so tight that current NCI director, John Upton, issued a memo of “very strict rules that should apply to the interaction” between the two institutions. The memo has seven points calling for board examination of ACS requests for support rather than the usual automatic granting of funds14.

State and Regional Institutions

Most NCI funds go to treatment programs and related institutions. (A plurality of funds, 35 percent, go to “profit-making institutions”15.) One such institution is the Michigan Cancer Foundation (MCF). The MCF received $6.2 million, as much federal funding as the combined support of the two largest state universities in Michigan in 1978, which was $6.3 million16. In an interview with Joy Harsen, head of Health Education (public relations) at MCF, it was established that there were several branches of operations, including breast cancer detection, several cancer patient field services, immunology research, human virus containment, and a chemical carcinogenesis unit. This latter unit, however, “takes no advisory action of its own but relies on FDA decisions.” The chemical carcinogenesis program “collaborates with industry, labor, and local government” and has an advisory panel of the same elements. A breakdown of funding sources and allocations for the MCF was explicitly refused during two interviews, despite $6 million in public funds involved.

The Cancer Screening Project is a part of Cancer Action Now, a field service funded mostly by ACS (money from federal NIH grant NOI-CN-65252 but administered by MCF) and run by the Detroit Health Department. Cathy Courtney, Health Educator, gave details of the attitude prevalent in the actual execution of the cancer project in an interview at the Health Department.

Much of the educational “outreach” funded by NCI is actually fundraising for MCF. Many of the programs provide jobs for job’s sake and so change or action is difficult. There is widespread “institutional resistance to admission of environmental causation.” Examples given were well-established cases such as DES, Agent Orange, the Pill, PCBP, and asbestos. Courtney spoke of minimal preventative measures which could be employed in education by Cancer Action Now, such as HEW Secretary Joseph Califano’s six dietary points, but the program supervisor “takes the attitude of, ‘no, don’t tell them that stuff, just go get tumors.’ ” The whole unit is motivated to report as many tumors as possible.

Political Conflict

Clearly, at all levels of funding and control by federal and private institutions, there is an aversion to studies of environmental causes of cancer. When such studies are done, little action is taken. It would be difficult to defend this inaction by saying “the data aren’t all in,” because we balk about even collecting data about our environment. It is easy to say that doctors occupy positions throughout these institutions, so they decide matters in a self-interested way. It is more insightful to look deeper into the social and economic fabric of the system that supports our medical system and its cancer research.

The ideas that govern research have a material social basis (17). The material factors that contribute to the treatment-oriented medical research establishment are the previously mentioned historical trends, the investments of drug companies (whose tremendous influence on the medical schools and hospitals has been documented elsewhere (18, 19)), the cart-before-the-horse bias of available technology on research interests, and the interlocking of private interests and business practices with the decision-making bodies of public welfare organizations such as the NCI. Without hard financial backing and without intellectual “nourishment,” some ideas (such as prevention) will certainly languish. Certain other formulations of the cancer problem will receive support, by no accident.

In David Ozonoffs analysis of the political economy of cancer research, he quotes a researcher speaking about the mechanistic approach to cancer: “ ‘Although the removal of the carcinogen from the environment is obviously the most effective way to conquer cancer, it may require such a rearrangement of the environment that society cannot or will not allow this to be done except slowly over decades. A knowledge of the steps in the carcinogen process will almost certainly lead to ways to interrupt the process in the continuing presence of the carcinogen’ ”20. Ozonoff continues: “In this context, ‘rearrangement of the environment’ is another way to say interfering with the economic and social structure, while the ‘society’ that objects is, of course, the small group of people known as the U.S. ruling class.”

A political analysis of cancer research must also involve a look at cancer amongst Blacks. When considering cancer in Blacks it must be borne in mind that Blacks have no physiological propensity for cancer, but that their numbers are predominantly working class, urban, poor, and with health care less adequate than the better-off classes.

At the Senate National Cancer Program hearings, extensive data about Black cancer demography was provided. In the past 25 years the overall cancer incidence rate for Blacks went up 8 percent while the rate dropped 3 percent for whites. During the same period cancer mortality increased 26 percent for Blacks, 5 percent for whites. From 1949 until 1967, the yearly mortality increase was twice as high for Blacks as for whites.21 Another study cited showed that from 1950 to 1967, mortality increased 20 percent for Blacks and about 0 percent for whites. Some explanations that have been suggested are “poor screening and educational programs, diagnosis of cancer at more advanced stages, less timely or delayed treatment, and higher environmental risks”22. The implied solution is vast expansion of the current medical-industrial complex. In fact it was stated in the conclusion of the NPC presentation that, “cancer management is so difficult and time-consuming that the already overloaded and understaffed facilities for medical care of Black patients may be put under a severe strain by an increase of Black cancer patients.” It was further concluded that the only way to stem the exponential increase of Black cancer is to study environmental influences.

The affluent class in this society benefits most from a treatment oriented attack on cancer, since cancer rates are highest among the poorer groups such as workers and Blacks. To treat rather than prevent cancers would make most sense to the lowest incidence group. Treatment would make the most sense to those who could count on the best treatment. Thus, there is a contradiction between ignoring our present political and economic system and endeavoring to prevent cancer.

Research and Action

Much emphasis has been placed on dietary and lifestyle changes as the most important preventative measures against cancer and ill health. “There is a growing realization that lifestyle plays an important role in the ecology of disease. If there is a health crisis in America today, it is largely a crisis of lifestyle in which destructive habits such as alcohol use, drug addiction, lack of exercise, malnutrition, overeating, cigarette smoking, careless driving, and sexual promiscuity create health problems”23. Put more bluntly, “cancer occurs because of something we do — we eat certain foods, we drink, we smoke, we choose a certain way to live”24. In this admonition, the victim is blamed for cancer resulting from her or his “lifestyle.” (Imagine telling the tubercular child laborers in Chicago, in Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle,” that their problem was diet and then giving them six points of “wise nutrition”!)

Do-it-yourself health prevention is expensive, reaches only the best educated, meets intense competition with a system which predominantly markets the “bad” lifestyle, and is difficult to figure out. Though much is now known about diet and environmental risks, one needs a graduate medical education to understand what is now presented to the public. Misinformation is widespread, much to the benefit of the food and health industries. An example of the industrial-academic nexus is the academic journal Nutrition Reviews. It is a “legitimate” research journal put out by the Nutrition Foundation dedicated to “advancement of nutrition knowledge and to its effective application in improving the health and welfare of mankind”25. Its board of trustees includes directors, vice-presidents, etc., from Stauffer Chemical Company; Specialty Chemical Group, Inc.; Hoffman-LaRoche, Inc; Life-Savers, Inc.; Revere Sugar Co.; The Coca-Cola Company; Oscar Meyer and Co.; The Nestle Company, Inc.; U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare; Libby, McNeill, and Libby; Monell Chemical Sense Center; Miles Laboratories; and Dow Chemical Company.

There are truths about dietary prevention of cancer that are derived from research efforts. Rather than ignore them, it is useful to consider the nature of our food sources. Most of the food bought by the American public in supermarkets is a chemical-industrial product — refined, processed, transported, and marketed so as to yield higher profits. This attitude toward food (and toward our environment and much of the hardware that surrounds us) allows “lifestyle” to be lumped more easily under the broader category of industrial-chemical environmental “insults,” which must be more extensively included in our research programs if cancer is to be effectively battled. In other words, our food and objects around us should be considered just more environmental chemicals.

Testing for Carcinogens

There is a great deal of confusion surrounding the testing of chemicals (occupational insults, food, petrochemicals, etc.) for carcinogenicty. Part of the problem has already been discussed; only 1 percent of the NCI budget goes into testing, and the documentation-registry program is neglected. Much of the controversy and ambiguity could be eliminated by testing and epidemiological follow-up.

There are some 70,000 chemicals currently in industrial use and about 700 new ones are added each year, it is widely acknowledged. Even if only a few of these are carcinogenic, a serious health hazard is present. Thus far, assays have correlated well with epidemiological studies to the extent that all of the chemicals showing carcinogenicity in animal tests show some correlation with human epidemiological studies when such human data are available 26.

In addition to testing, it might be decided that certain chemicals are not needed after their cost to society is considered. “Many classes of chemicals are known to be more likely carcinogens than others. Sulphuric acid and other basic industrial ingredients are simple inorganic compounds which are not likely to be carcinogens. Most of the carcinogenic ones are, in fact, chemicals that have been introduced recently as replacements for perfectly satisfactory materials that have been used for generations, even for millenia. Many of these carcinogens, in fact, have been introduced just for profit. The majority of byproducts of petroleum refining and plastics manufacturing, by the nature of their chemical structures, are likely to be carcinogenic. But uses are sought for them just the same” 27.

For those chemicals deemed necessary, testing should be easy. Testing would be exhaustive if even 1 percent of the $100 billion cost of cancer to society 28 were not externalized (excluded) from corporate profit calculations. The cost of testing each of the 700 new chemicals each year is $200,000. The total, $140 million, is .4 percent of the gross profits of the chemical industry in 197629. The costs are trivial. If the expected rise of cancer incidence in the early 1980s occurs, “trivial” will barely describe the cost ratio between testing carcinogens and the cost to society of cancer. (At the time that this article was being prepared, two easily understandable evaluations of the cancer problem were published that consider externalized costs and corporate hindrance of the solution30,31.)

Despite the obvious benefits of accurate chemical testing, the NCI bioassay subcontracts continue to be awarded to industrially-owned testing facilities32! The few doctors and researchers who are sympathetic to fundamental change in attitude toward cancer research testify endlessly but produce few results. HEW and the FDA are repeatedly paralyzed and hesitant to act because of outside influences. Legislation affecting our “sea of carcinogens” is lobbied out of existence, often by groups like the American Medical Association (AMA), ACS, or MCF, in conjunction with industry.

So, rather than the data not all being in yet, we are not researching the fundamental ecology between people and the chemical environment. When we do act, great impediments arise from non-scientific and economic forces such as business interests, the medical-industrial lobby, and the ideology of a nonrepresentative capitalist ruling class. The major solution to cancer — social planning — has little to do with present cancer research.

The entire social environment33 should be considered so that the very need for the existence of certain industries and chemicals could be an overall consideration in cancer research. It might be shown empirically that good health is inconsistent with a system that allows private companies to externalize from their responsibilities the effects of their processes and products on society. “A framework for clinical investigation that links disease directly to the structure of capitalism is likely to face indifference or active discouragement from the state”34, so an approach to researching cancer goes far beyond simple debate of technical points within the medical-academic arena. The research must be politicized at the laboratory and institutional levels and must include social and economic considerations. To politicize cancer research will surely challenge the institutions and ideology of capitalist health care practice.

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 3 <<

REFERENCES

- Armelagos, G., and Katz, P., “Technology, Health, and Disease in America,” in Ecologist, 7(7), p.35, 1978.

- Personal communication.

- McKinley, S., and McKinley, J., “The Questionable Effects of Medical Measures on the Decline of Mortality in the United States in the 20th Century,” monograph, 1978.

- Basic Data Relating to the National Institutes of Health, (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1979) pp.2-4.

- Broad, W., “NIH Deals Gingerly with Diet-Disease Link,” in Science, 204, p.1176, 1979.

- Broad, W., “Jump in Funding Feeds Research on Nutrition,” in Science. 204, p.1059, 1979.

- Broad, “NIH Deals Gingerly … ,”

- Broad, “Jump in Funding … ,

- National Cancer Program — Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Health and Scientific Research of the Committee on Labor and Human Resources — United States Senate, (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1979) pp.195-200.

- Ibid, pp.232-272.

- Ibid, p.235.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p.274.

- Ibid, pp.199, 212.

- 1978 NCI Fact Book (updated), (NIH Publications, 1979) p.36.

- Ibid, p.35.

- Ozonoff, D., “The Political Economy of Cancer Research,” in Science and Nature. 2, pp.13-18, 1979.

- A New Outlook on Health. Ann Arbor Alternative Politics Collective, 1979, p.12.

- Concerned Rush Students, “MD’s in the Drug Industry’s Pocket” in Science for the People,8, (6), pp.6-21, 1976.

- Farber, E., in Current Researches in Oncology. 1973, from Ozonoff, p.16.

- NPC Hearings. pp.314-351.

- Ibid, p.315.

- Armelagos, p.33.

- Gonzales, N., “Preventing,” in Today’s Health. May 1976, p.30.

- Nutrition Reviews. 36 (11), back inside cover.

- NCP Hearings. pp.195-197.

- Ozonoff, p.17.

- NCP Hearings, p.469.

- Ibid.

- Moss, R., “The Cancer Establishment,” in Progressive. 44(2), pp.14-18, 1980.

- Epstein, S., “Cancer, Inflation and the Failure to Regulate,” in Technology Review. Jan. 1980, pp.42-43.

- NCP Hearings. p.195.

- Conrad, F., “Society May Be Dangerous to Your Health,” in Science for the People. 11(2), pp.14-19, 1979.

- Waitzkin, H., “A Marxist View of Medical Care,” in Science for the People, 10(6) ,pp.31-42, 1978.