This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Molly Coye, Health Activist for the OCAW

by the Editorial Collective

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 2, March-April 1980, p. 22-26

Molly Coye is a physician and chief of the Occupational Health Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital, and an advisor to the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union. She has a background in both Russian and Chinese studies and has traveled extensively in Cuba and China. She was active in antiwar work and in support of recognition of the People’s Republic of China.

SftP: You said that your trip to China led you into health care. How did that happen?

Coye: I had been to China in February ’72, and I spent two years giving lectures on China. When I talked to people about worker control of the factory, their eyes glazed over. But when I talked about a health care system which was run by the community and in which many of the people doing health care work identified themselves as community members and not as health care professionals, that got them very excited. I ended up going into medicine. That was a way to organize groups politically in America rather than simply appointing myself as missionary to the community.

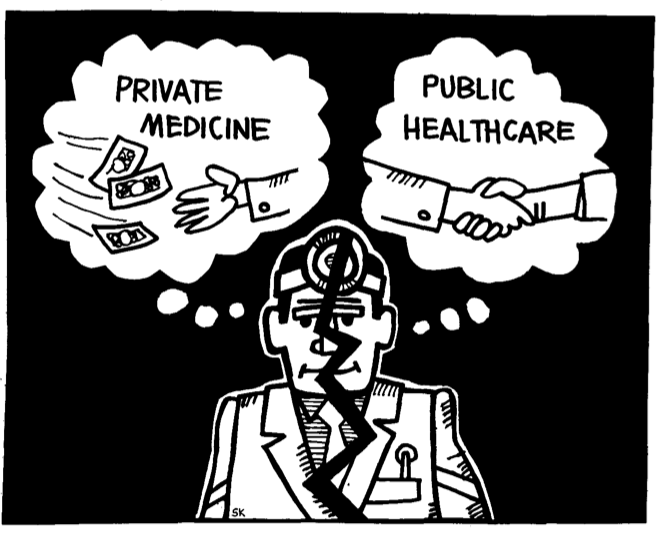

Issues of health care are close to God, Mother, and apple pie. It is easy for someone who has been raised in the U.S. to say that of course there is labor, of course there is management, and of course management makes profit off of labor. It doesn’t sound quite the same to say that of course there are doctors and of course there are sick patients and of course the doctors make a profit off the sick patients.

SftP: Is there much training in occupational health and safety in medical school?

Coye: The national average is less than ten classroom hours. I would say at Johns Hopkins we had far less. Usually the approach is to think there are a few specific diseases that are of occupational origin and that the majority have nothing to do with it, whereas the point of view that some of us take in the field is that there are very few symptoms that could not be caused or exacerbated by work. It is frustrating because I know that in other countries there is a great deal of education in occupational medicine.

I was suspicious of much of what was taught. For example, the chief of the urology department was a man who had operated on a large number of workers for bladder cancer. He knew that the reason they were getting sick was their exposure to aniline dye but had not informed either the workers or the union. My conclusion was that a great deal of what they would teach us was suspect. There is some very good literature in support of the fact that you can buy your doctor — you can find doctors who are biased and if you find the right one and keep hiring that doctor you get the results you want.

SftP: So you think there’s a conflict in the minds of some doctors, not only about healing people, but also slaying in business?

Coye: George Bernard Shaw pointed out that you pay a baker for the number of loaves he bakes and you pay a surgeon for the number of legs that he cuts off. You don’t pay him to keep a patient healthy. If you look at academic-based physicians, very few consciously think of trying to maintain illness; I do think you get closer to that danger zone when you talk about a company-paid physician, who’s being paid not to prevent illness, not to bring it up or not to tell the patient about it.

Occupational medicine is an uncertain art and physicians don’t like uncertainty. To venture into an area where they know there may be 70,000 chemicals of various toxicities that workers are exposed to and they don’t know what any of them does — they’re opening a Pandora’s box and they don’t feel very secure about it.

SftP: You’re been active in occupational safety and health with the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union (OCAW). Can you tell us about that?

Coye: I’ve been with OCAW about four years. As a medical student, I took part of my training with them. OCAW has been one of the most progressive unions in occupational safety and health. They were instrumental in the passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act in 1970, and have been one of two or three unions that consistently brought OSHA to court to force them to promulgate standards. A good deal of this work was developed by Tony Mazzocchi, who was Vice-Presient and is now Director of Health and Safety.

One of the hardest things for people to accept is that you can’t do anything about health and safety without a union. People at the bottom — Blacks, Chicanos, Filipinos, Vietnamese — lose out in every way. They have more exposure, are paid less, and are less likely to be unionized. People working with the unorganized on health and safety are most honest when they don’t promise to be able to do anything until the workers are organized into a union. It’s hard enough even with a good union behind you to take on a management determined to fire people who are agitating around health and safety. The protection under OSHA says the employer can’t discriminate against an employee for having been active on health and safety. There have been successful cases but you’re talking about three or four years in court with no salary.

SftP: How does OCAW handle occupational health and safety?

Coye: OCAW was one of the first unions to set up a health and safety department. They have employed a full-time industrial hygienist since 1975. They also have a Health and Safety Coordinator who edits their monthly newsletter. They hired a physical chemist for a couple years in the early ’70s. They got a grant from OSHA two years ago to hire five doctors to work in the health and safety department. They also have had student internship programs for many years for hygienists, nurses, etc.

They have been instrumental in attempts to get new legislation passed, and to use the courts to enforce legislation. They have, as of two years ago, a new program where, in each district in the country, a member of the rank and file gets paid time to leave the plant, train at headquarters in Denver, and then travel around the district visiting different locals and working on development of health and safety committees.

SftP: How do things stack up when you’re up against company experts?

Coye: The range of exposures about which the health and safety department has to be knowledgable is tremendous, as you can see by imagining the exposures you have in such a union. In a negotiating situation, there are company-employed hygienists and physicians who know the ins and outs of their set of exposures. Going against them, the union docs or hygienists have had maybe three or four hours to put through some research before negotiations or court. So you have a thin spread of resources. The only hope is that the unions’ small professional group can be used as backup to very strong health and safety committees within the locals.

I try to respond to lots of different requests and do as much as I can with a small amount of time. Another response would be to learn everything there is about the hazards of, say, lead, so you can be the pro-union advocate. We need people who concentrate on one particular substance, though in some cases you don’t need specialists.

There’s a great story. Back in 1976, the first case I went into for OCAW, I went to negotiate a medical plan and protection for workers exposed to mercury. I was a fourth year medical student then. I did basic reading in the texts and came with xeroxes on mercury and the existing legal standard: a blood level of 10 mcg/.ml. The company paid for the national expert on mercury effects to come in on their side. The fellow said that he didn’t worry about levels of 50 to 100 mcg/ml, which many of these workers had! In several factories he’d worked with, people had been up to 200, and he didn’t think there was any real harm done! All I had to do was read chapter and verse from the medical texts to the negotiating committee for the union to feel tremendously strengthened that they had right on their side.

SftP: Some of the entrenched unions see health and safety as a threat. Who’s supporting it and who isn’t?

Coye: One of the most dangerous postures to get caught in right now is that of attacking unions. What you’re looking at is one of the contradictions of industry under capitalism. With increasing productivity of work and the introduction of new materials with industrialization, there also results an increasing sophistication of the work force. In this country, older workers are more comfortable with safety questions, whereas younger workers, influenced by the environmentalists of the ’60s, may be more open to the concepts of chronic disease, delayed disease, cancer. On the other hand, older workers are seeing their peers dying off with these cancers and lung diseases and want to protect the next generation. Part of the next generation is saying, “What the hell, I’m going to die of cancer anyway, why protect myself?” So, it cuts differently in each local you work with.

SftP: Now we have OSHA. largely the result of union legislative pushing. What can be done next?

Coye: There are issues which are tremendously important. An example is ‘right-to-know’ legislation. It’s good to organize around because it’s obvious to workers that they ought to have that right. A labeling standard has been formulated bv OSHA. There’ll be many battles over the actual obtaining of the information, battles over trade secrets, proprietary rights, etc.

There have been several stages, beginning with the concept of safety as the number one health problem in an occupational setting and compensation as the way to deal with that. Then in the ’60s and ’70s we moved to the concept of chronic or delayed-onset disease, and the idea of prevention of exposures to certain chemical and physical agents. In the ’70s, we’ve begun to emphasize stress. Workers are talking openly about the links between speed-up, shift-work, and other questions of the work process. To the extent that we can redefine occupational disease as disease that results from all aspects of the work process, we can redefine the issue as control of the work process itself. Then we’ll be headed in a good political direction. Occupational disease can be conquered only by the preventive step of controlling the processes themselves. Illuminating this is really our role as health professionals.

SftP: Many people think that we have to accept occupational hazards in exchange for a high standard of living. This argument is applied not only to occupational health and safety, but to environmental issues. How do you respond?

Coye: With two answers. There are different levels. In terms of work-place, the way you have it now, workers get all the risks and management gets all the profits. One way to approach this with workers is, “Let’s equalize the situation. Let’s redistribute profits.” That’s talking standard of living. When management raises, “This is going to cost something,” raise the issue of the profits of management and why some of that shouldn’t be redistributed for health and safety. Obviously, what you’re headed for is redistribution of profits on a larger scale. What you’re using health and safety for is to get at that larger question and also point out that those profits are being taken at the cost of the risk the workers incur. What we are talking about is equality of access to what are the presumed benefits of our level of industrialization and consumption.

The second level of the question is “What’s the real cost to society?” This is one of the hardest things to raise at the same time you are discussing the first issue. The major point is, in the 4000 years we have had written history and civilization, there has been no change in our bodies’ protective mechanisms. We are not designed for most of the assaults on our bodies in the environment or in the workplace — not just synthetic materials, but things which are natural, like asbestos. We’re exposed at a level which was never possible 4000 years ago. The question is not whether to have a lower standard of living, but what materials we will use to construct our higher standard of living; we’re never going to be able to deal with it until we have socialism, because the issue of equality of access is always going to take priority. The second level is going to be seen as a luxury of the middle class, which it is at this point. I don’t think you can successfully use the second issue as an organizing issue in a capitalist society. That has been one of the failures of the environmental movement. But it is a real issue and if we don’t get socialism we’ll never deal with it in time — we’ll mutate ourselves off the earth, or whatever.

The basic contradiction is between productivity – and in capitalist models development is defined as increasing productivity — and worker health and safety. The contradiction is blatant under capitalism. What happens to it under socialism? Is this the “declining productivity” which appeared in the early ’70s in China? Do you sacrifice worker health and safety, or do you find some other ways of stimulating productivity? There is a bottom floor level of productivity you have to maintain to feed society, and the issue in China was that there was such a drop that there were actually hunger marches and a real dislocation of society.

SftP: You’ve seen some socialist models of occupational health and safety. What have you learned?

Coye: There are a couple of things I saw in Cuba. They have enormous strength in the health care system. The organization of primary health care promotes awareness of occupational health problems in the community and factory. Beyond the fact that all workers have free health care, each community health center — ‘polyclinics’ is what they’re called — is responsible for sanitation of all workplaces in its area. They do inspections on an annual basis to enumerate hazards and, in the case of national priority hazards, do medical testing. They almost never see acute lead poisoning anymore. Every worker exposed to lead is identified by their polyclinic and receives a minimum once a year screening. If found to have an elevated blood level the worker is withdrawn from work at full salary and an investigation is made with authority to shut down the place for modifications. Identifying the hazards in each workplace and having a national priority system [for assessing hazards] is an incredible achievement even for an industrialized country, and in an industrializing country is a major challenge.

There are production assemblies at every work unit once a month, which 70 to 80 percent of the workers attend. All inspections of health and safety must be reported to the assemblies, and at the next assembly the administration has to answer with their plans to meet the criticisms. Every productive unit must include a budgeted item on health and safety in the administrative plans which are submitted to the appropriate industrial ministry each year.

Most workers are involved in ’emulation campaigns,’ a combination of moral and material incentives to stimulate participation and productivity. One of the five points which workers must “emulate” to win a prize is ‘health and safety.’ A work group will not win their prize if one or two members are careless. Therefore there’s a lot of peer pressure built into the system.

All workers have pre-employment exams and yearly exams. At present, these are only very cursory exams designed to detect TB, VD, and other communicable diseases. One of the maor projects of the Ministry of Public Health is to design more specific preemployment and periodic exams.

SftP: Did you get any information on stress situations?

Coye: Every local in the plant has a health and safety representative who has a kind of “welfare” function of identifying people who are troubled. They can go higher up in the union or to the polyclinic. There is a clear recognition in every polyclinic I was in that people experience stress at work. I’ve never heard anything about stress reduction therapies or ways to make people adjust to stress. Their attitude seemed to be that either the work conditions should be changed or the person should be rotated out. But it’s not talked about very much, and after a few weeks there I realized we were talking in terms of chemical and physical hazards almost exclusively.

As a matter of fact, it was ironic. When I was asked to give a talk on ‘Occupational Health and Safety in the United States’ recently at the end of my second visit, I talked in terms of physical and chemical hazards, reflecting their interest in that. When finished, there was a question-and-answer period. Half-way through, a guy stood up, said he was a psychologist working in occupational health, and was very puzzled that all I talked about were chemical and physical hazards. “Don’t you think there is any role for stress in disease?” I thought it very ironic to be hoisted on my own petard.

SftP: What about the education of health professionals?

Coye: All medical students have a unit on occupational health and all spend several weeks rotation time in workplaces. All their training in polyclinics includes noting the work of every person who comes in. There are residencies in occupational medicine offered in the two medical centers and many go abroad for training in occupational medicine, primarily to Bulgaria.

SftP: Did you see anything negative that particularly stuck out?

Coye: They have the same tendency you see here on the part of professionals working in health and safety, not to want to open up more problems than they feel they can deal with. They feel they can screen for certain exposures and for certain chemicals. Since they have limited resources they don’t see the point of educating workers about the myriad exposures they face, when they can’t do anything about it. But that’s carping, because the awareness of workers in Cuba of occupational health and safety is so much higher than the workers here. For example, outside of Santiago de Cuba I spent time talking with agricultural field workers, and they knew more about the effects of organophosphate exposure than most workers I’ve talked with in California. They monitor exposure by means of cholinesterase testing every three months, and they have for 18 years.

SftP: How have Cuba and China dealt with the contradiction between productivity and occupational health and safety?

Coye: The first question to raise is what happens when a country experiences a troubling decline in, or at least a plateauing of, the previously rising productivity of the economy.

This occurred in both countries. Both Cuba and China experiemented in the mid-’60s with mass spontaneous participation in government, both in workplaces and in the community. In Cuba, that led to a late ’60s decline, and they made a decision to recreate the trade unions in ’73 and increase emphasis on popular participation and control in more organized ways.

In China, the timeline becomes different. In the early-to-mid ’70s there was a severe decline in the rate of productivity to the point where there was difficulty feeding the population. The response, after the fall of the Gang of Four, has been to believe that increase in productivity will be possible only by emphasizing efficiency and relying in part on some management techniques from capitalist nations. It’s early to guess how predominant this experiment will be. I think we owe it to the Chinese as our brothers and sisters who have been struggling for socialism to communicate the difficulties Taylorist (‘scientific’) management techniques have created for our workers in general.

The acceptance of foreign aid — not just machines but management techniques as well — is a problem. On top of that, how much of the work process is defined by the technology you import? All these questions are troubling. There must be a good deal of debate in China about this. Rather than saying, “Well, China’s taken the wrong turn,” it’s important to discuss things with them to the extent that we can. We’re talking about a country that is having trouble feeding 900 million people, and part of the temptation must be the hope of an easy solution.

|

San Francisco Worker’s Clinic Few clinical facilities in the United States offer a worker medical care that includes adequate consideration of the possibility that one’s job may be hazardous to one’s health. For more than a year now, such a facility has been in operation at San Francisco General Hospital. Located in one of the hospital’s clinical spaces one evening a week, the Occupational Health Clinic offers much more than medical care. Information on hazardous exposures and legal assistance are also available. About half the patients are referred by their unions, and this proportion is increasing. Interest from unions has been strong, and the Clinic has provided much information helpful to unions in battles over health and safety. In fact, one-third of the patients have no medical complaint at all, but want education about some aspect of their workplace. The cost to patients follows a sliding scale or is picked up by the worker’s insurance. Lab costs are paid for by the patients, but Clinic staff is seeking funding for this. No one is turned away for lack of money. The volunteer staff consists of about 40 people, with half assigned each Tuesday night. Staffers speak Spanish and Chinese. The twelve physicians come from the hospital house staff and faculty, as well as from local community clinics. Among them are a toxicologist, a pharmacologist, and an occupational medicine specialist. There are seven industrial hygienists and 15 health educators, who serve as patient advocates. Four lawyers are on staff and sit in when legal questions arise. Most of the staff came to work at the Clinic with the idea of doing political work in a unique setting. The Clinic works with the newly-formed Bay Area Committee on Occupational Safety and Health (BACOSH), with BACOSH doing much of the extensive outreach. Each patient sees a team of three: physician, hygienist, and patient advocate. An initial evaluation takes about an hour and a half, including a physical examination and tests if needed. There is a discussion about what the plan is, and what follow-up might be needed. A large number of patients come in for only one visit, because they’ve already been diagnosed as having some condition and they want to know if it might be work-related. The Clinic does not routinely handle Worker’s Compensation cases, due to staff time limitations; but if a case shows promise of expanding the definition of compensable disease, the legal staff will work on it. In addition, educational materials are dispensed and liaison work is done with the patient’s union. Between weekly sessions, appointments are taken and both preliminary and follow-up research is done. As one staffer explained, “When a patient comes in and reports 20 chemicals at their worksite, you do a lot of scrambling to look them up.” In addition, Clinic committees meet: outreach, education, steering, and a group for each profession within the Clinic. Administrative work is done on a rotating basis. Not all of its work is done within hospital walls. Staff members will monitor worksites and do epidemiological studies. In one case they worked with a union to design a questionaire, collect information, and complete the research to identify a baffling clinical syndrome among workers in a new building. Over the course of its year, the Clinic has gone through many discussions about the nature of the work, for given the social context of occupational medicine it is not a purely medical enterprise. There have been struggles concerning elitism, and an effort is always made to keep the professionals in touch with the direct patient needs. Especially obvious is the limitation of only being open one night a week. Were it a full-time facility, it could accomplish far more than simply seeing a larger number of patients. As one staff member put it, “We’re a fly in the ointment of the normal functioning of the system. We’re far more symbolic than our actual ability to deal with the enormous number of occupational health problems. We’re a model of the fact that there is such a thing as worker medicine. There is such a thing as lawyers, health educators, physicians, and industrial hygienists who want to work for workers.” -Molly Coye |