This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Industrial Genetic Screening

by Jon Beckwith

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 2, March-April 1980, p. 20–21

Jonathan Beckwith is a long-time member of Science for the People and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School. He is currently active in the Boston Sociobiology Study Group.

“Next Job Application May Include Your Genotype, Too”

— Houston Chronicle, April 4, 1975

This newspaper headline reflects the trend in scientific and industrial circles to attribute occupational disease to the genetically susceptible worker. The connection has been made possible by recent developments in human genetics linking certain genetic disease states with the increased risk of specific diseases. While so far such examples are limited, the following ones appear to be among the clearest. Problems in the clearance of cholesterol, which can lead to heart disease, are in some cases due to well defined genetic defects referred to as familial hypercholesteremia. Genetic variations in certain proteins found on the surface of human cells (HL-A antigens) have been correlated with diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis, a progressive deterioration of the spinal cord. Individuals born with only very low levels of a protein called alpha1 – antitrypsin due to the presence of two altered genes (homozygous defectives) have a high probability of developing emphysema.

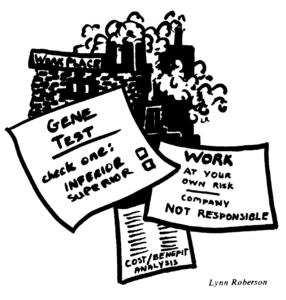

Although this research can certainly benefit individuals by helping them avoid the specific environmental insults triggering disease states, it also poses a threat to the occupational health movement. For at a time when many labor unions and scientists have finally become effective in fighting to reduce the use of toxic agents in the workplace, “genetic susceptibility” is an asset to industrialists. It allows them to argue that the pollutant-caused disease we see among workers cannot really be ascribed to the pollutant itself, but rather to the genetically-susceptible individual. The solution, then, is not to clean up the workplace, reducing or eliminating the exposure, but rather to screen out those workers who are most likely to be afflicted. But even in those few cases where a real correlation has been established between a genetic trait and susceptibility to a particular disease-causing agent, the supposedly “non-susceptible” workers are still exposed to considerable risk. And yet, these arguments are used to suggest there is no need to reduce occupational exposure to pollutants, and thus to maintain the high level of disease found in many industries.

The use of such arguments to avoid improving working conditions is not new. Earlier in this century, industrial spokesmen suggested that work-related accidents were caused by accident-prone workers instead of poor safety conditions. More recently, several industries in which high lead exposure is common have essentially forced women of child-bearing age to get sterilized. They have done this in lieu of reducing lead levels which endanger both male and female factory workers.12 Dow chemical and Dupont have instituted genetic screening programs for a number of different genetic traits including sickle-cell trait and partial alpha1 – antitrypsin deficiency, both heterozygous states.345 In both cases the evidence for disease susceptibility for the heterozygote is very weak or nonexistent.

Responsibility of Geneticists and Genetic Screeners

Scientific and medical research are not apolitical. Social, economic and political forces affect what research is done, how it is done and how it is used. When researchers studying genetic susceptibility publish such statements as, “Screening tests may become commonplace in industry where such exposure occurs, so that the employer can protect potential employees who are genetically susceptible from being placed in positions detrimental to their health,”6 they are unwittingly lending their support to one side in a societal struggle.

In an unequal set of economic relations as exist within American industry, scientists must work extremely hard to see that on matters of health all sides are considered equally. This means they will have to forge links with workers and progressive unions who are struggling over occupational health issues. They will have to take special pains to emphasize the broader issues of reducing to an absolute minimum exposure to pollutants. If scientists do not get involved in pushing to clean up the factories, they may find their work being used to cause more harm than benefit to people.

Genetic Susceptibility and Environmental Pollutants

The dangers posed by research on genetic susceptibility extend beyond the struggle for occupational health and safety. They pose threats to the environmental and nutrition movements as well. The latter have made great gains in alerting the public to the dangers of increased pollutants in the atmosphere and of chemical additives in our foods. Moreover, the 1970 Clean Air Act and the activities of the EPA and FDA have had a positive impact on government policy. However, in a new report prepared by a National Academy of Sciences Committee, we see the arguments of genetic susceptibility presented in a way that can blunt the effects of these movements:

But in societies of abundance, differential selection acts through the agencies of individual habits and ways of living, as well as through pollutants, drugs, chemical additives, and special occupational exposures almost too numerous to count. If one were to make universal preventive rules to cover such a multitude of threats, the life of asceticism such instructions would dictate would offer little fulfillment, and in any case human nature would cause them to be little honored. But to point out to a specific person the conditions under which his particular endowment may fail to protect him from impairment of his health offers some chance of rational behavior on his part.7

While clearly there is some truth to this analysis, this focus on the susceptible individual, instead of on societal changes, reflects a social perspective, not a scientific one. In effect, scientists have put themselves on the side of corporate powers in their struggles against a growing movement of people insisting on the right to take control of their own health.

ADDITIONAL READING

Powledge, “Can Genetic Screening Prevent Occupational Disease?” The New Scientist, Sept. 2, 1976, p. 486.

E.J. Calabrese, Pollutants and High Risk Groups, New York: J. Wiley’ Sons, 1978.

H.E. Stokinger and L.D. Scheel, “Hypersusceptibility and Genetic Problems in Occupational Medicine: A Consensus Report, Journal of Occupational Medicine, vol. 15, 1973, p. 858.

Since the writing of this article, a recent series of New York Times articles entitled “The Genetic Barrier: Job Benefit or Job Bias” has appeared. They give an excellent summary of the issues and present important new details on genetic screening in industry. (The series began Sunday, February 3, 1980, and continued for 3 more days.)

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 2 <<

References

- “Four Women Assert Jobs Were Linked to Sterilization,” New York Times, Jan. 5, 1979.

- E. Goodman “A Genetic Cop-Out,” The Boston Globe, June 15, 1976, p. 37.

- D.J. Killian, P.J. Picciano and C.B. Jacobson, “Industrial Monitoring: A Cytogenetic Approach,” Annals of the New York Academy of Science, vol. 269, 1975, p. 4.

- C.F. Reinhardt, “Chemical Hypersusceptibility,” Journal of Occupational Medicine, vol. 20, 1978, p. 319.

- G. Bronson, “Industry Focuses on Hypersusceptible Workers Prone to Allergies, Other Maladies Caused on the Job,” Wall Street Journal, Mar. 23, 1978, p. 46.

- J. Lieberman, in Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 57 no. 3, 1973.

- “Genetic Screening: Programs, Principles and Research,” National Academy of Science, Washington, DC. 1975, p. 17.