This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Society May Be Dangerous to Your Health

by Fran Conrad

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 11, No. 2, March/April 1979, p. 14—19 & 32—38

Chest pain, coughing and dizziness brought Joe to the doctor, who performed a check-up and advised him to quit smoking. The doctor never asked about the fumes Joe found so irritating at his factory job. Nonetheless, smoking didn’t help, Joe knew, so he went back to the job, resolving to cut out cigarettes except while working. He’d seen others lose fingers on the unprotected machinery he worked with, when they got bored or agitated. Smoking helped him stay calm and steady at this job, and it might help him keep his fingers. He decided not to smoke on breaks or at home. Why expose the kids to smoke and set a bad example as well? On his next break he picked up a magazine. An ad showing a sexy male relaxing in the country with a cigarette caught his eye. Automatically he reached for his pack, then stopped himself.

Chest pain, coughing and dizziness brought Joe to the doctor, who performed a check-up and advised him to quit smoking. The doctor never asked about the fumes Joe found so irritating at his factory job. Nonetheless, smoking didn’t help, Joe knew, so he went back to the job, resolving to cut out cigarettes except while working. He’d seen others lose fingers on the unprotected machinery he worked with, when they got bored or agitated. Smoking helped him stay calm and steady at this job, and it might help him keep his fingers. He decided not to smoke on breaks or at home. Why expose the kids to smoke and set a bad example as well? On his next break he picked up a magazine. An ad showing a sexy male relaxing in the country with a cigarette caught his eye. Automatically he reached for his pack, then stopped himself.

After work he squeezed onto a rush hour subway, wondering if jogging the five miles home wouldn’t be better. But he was beat as usual and besides he wondered how beneficial it was to jog in rush hour traffic. At home his wife told him that the bill collector kept calling, and asked where she was going to get the money for the kids’ dental bills. He took a drink, trying to relax so he could think about this other set of problems. He just couldn’t resist a cigarette.

He realized he was drinking and smoking more these days, two habits which were upsetting his health and upsetting his wife. She had become increasingly worried about his health and pleaded with him to reform. He did not want to hear her pleas and conversation between them grew more strained. Sometimes he felt caught in a vise.

Joe is a composite of people experiencing the assaults on health which are most typical of current American life. He may be at risk for a number of ills, including heart disease, hypertension, cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, ulcers and others. The doctor telling him to quit smoking, while ignoring not only job hazards, but the reasons for his habit, is in keeping with the current fashion among health professionals, who point to “lifestyle change” as the solution to many ills. Recognizing the impact of smoking, eating and exercise on heart disease, cancer and diabetes (the top three killers), they urge people to make more healthful choices. Typical of the trend is Blue Cross’ educational program, “Health Thyself”. The introduction states:

The major killers of the 1970’s – heart attack, cancer, stroke and accidents … may … be prevented – not by medical miracles, but by the individuals who decide on their own to avoid poor diet, physical inactivity, alcohol and smoking.1

The same attitude is reflected in the 1978-79 plan of the Boston area Health Systems Agency:

Our plan assumes that the principal determinants of personal health are individual behavior and lifestyles and that people must accept responsibility for their own well being …

The plan also states that “A healthful physical and socioeconomic environment should complement healthful behavior.” But in its implementation strategy, there is plenty on education toward behavior change, and nothing at all dealing with improving the “physical and socioeconomic environment.”

The idea is carried into the realm of morality by the president of the Rockefeller Foundation, John Knowles, who states, “I believe the idea of a ‘right’ to health should be replaced by the idea of an individual moral obligation to preserve one’s own health.”2

Certainly we could all improve our health by making the suggested behavior improvements. But the perspective that urges us to do so is a socially uncritical one, and fails to address the larger social forces which shape our health choices and otherwise affect our health. Such forces, this paper will argue, are more important than lifestyle choices. For example, a recent HEW report states that lifestyle choices explain only 25% of the risk of heart disease. “Although research on this problem has not led to conclusive answers” it goes on, “it appears that the work role, work conditions, and other social factors may contribute heavily to this ‘unexplained’ 75% of risk factors.”3

At best, the lifestyle perspective may help some individuals to improve their health. Lifestyle changes may help individuals to gain a sense of control which makes them more open to taking part in broader social changes, but are more likely to engender a feeling of purely individual achievement and of superiority over less successful people, given the dominant ideology of competition and pursuit of self-interest in our society. At worst the lifestyle perspective makes people feel trapped by the heavy burden of their own sloth, of being up against big odds in an endless isolated struggle to be “better”. The overall effect is to deflect people’s attention from the social causes of our ills, and as a long range strategy it will not have any impact on national health. It will instead serve as justification for the growing trend of cutbacks in health care and for industry’s struggle to minimize regulation of occupational and environmental hazards.

The purpose of this article is not to devalue the importance of education for individual health improvement, but to put it into perspective. Clearly there is need for change at both an individual and a societal level. But it is the thesis of this article, that not only is social change far more important than individual change toward improving people’s health, but that individual health change is not possible on a large scale without broader systemic change. After identifying which individual choices do influence health and what social factors shape these choices, most of the article will look in some detail into other ways that society has impact on our health.

How Individual Are Our Choices?

Diet has been linked to the big three killer diseases and several others: excess fats have been linked to heart disease and cancer, excess sugar to tooth decay, excess anything (i.e. too many calories) to obesity, which in turn is associated with high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes. Lack of exercise can compound the effects of overeating and may help to cause heart disease and the obesity-related group of illnesses. Possibly the most devastating form of self-abuse is cigarette smoking, which is unquestionably associated with lung cancer and other respiratory diseases, heart disease, high blood pressure and problems affecting almost every part of the body. Alcohol is of course the main cause of cirrhosis of the liver, and may also lead to other problems including birth defects and malnutrition. Stress also is sometimes listed under the rubric of lifestyle problems, for if we cannot always do much about its causes, we can learn some techniques for minimizing its destructive physical effects.

While it would be extreme to say that individual behavior is entirely determined by social factors external to the individual, the current focus on individual choice errs in the opposite direction. Certainly we make choices, but equally certainly, the habits, desires, values and experiences that guide our behavior do not develop in a vacuum. In the case of consumption of harmful substances, it is fair to say there are very powerful efforts going on to influence our actions in ways which do not improve health.

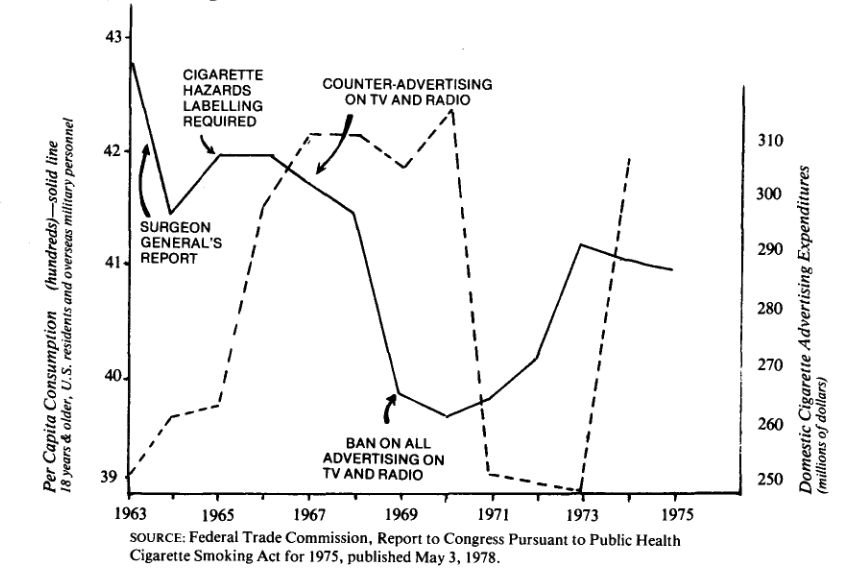

Cigarette ads and promotion for example, totalled nearly $500 million in 1975.4 Examination of the history of cigarette advertising reveals not only the power of the media over our choices, but also the subjugation of health considerations to profitability. Cigarette consumption rose steadily from about the time of WWI until 1963. Then there was a decrease in smoking for a few years followed by an upturn (Fig. 1). In 1964 the Surgeon General’s report on smoking hazards appeared and the following year Congress required the warning label on cigarette packs. As the graph shows, there was a slight downturn in cigarette consumption following the report, then consumption began to increase again. This rise coincided with increased advertising by cigarette companies.

Then, a curious thing happened. A private citizen brought to the FCC’s attention the fairness in advertising doctrine, which required equal time for countermessages when a controversial issue appeared on radio or TV. The idea was that cigarette advertising should be considered controversial, and anti-smoking messages should be mandated. The FCC did not grant equal time, but in 1967 it did issue a ruling that broadcasters who advertised cigarettes had to inform their listeners of the health hazards of smoking.

During the period following that decision a number of creative educational messages were aired opposing cigarette smoking from the American Cancer Society and other groups. Interestingly enough, when the pro and con messages appeared simultaneously, cigarette consumption began to drop more sharply than it had in 1964. The cigarette companies saw that the countermessages seemed to be effective, and not surprisingly, they were part of the pressure which led Congress in 1969 to ban all radio and TV advertising of cigarettes. Once messages and countermessages disappeared, consumption once more began to rise.5

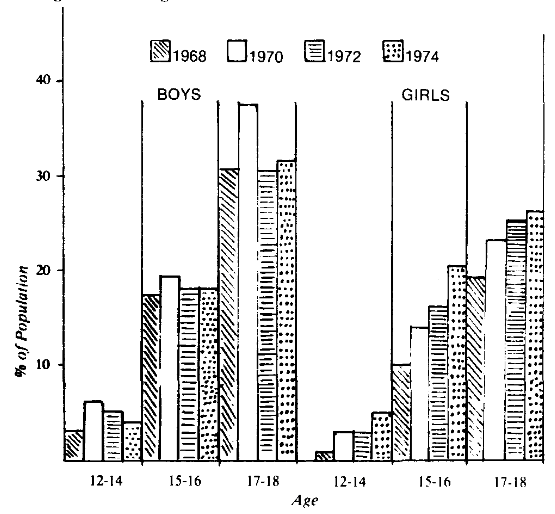

In the last several years, consumption has declined overall. But for whatever reasons, it is still increasing among teens, particularly females (see Figure 2). Meanwhile, the cigarette industry is seeking to exploit the potential market of this group by increasing its advertising in non-TV / radio areas. In the five years following the media ban (1970-1975) outdoor ads (like billboards) received a 10-fold increase in expenditures, the largest % increase of any advertising category.6 Observation of the hip women and sexy young male smokers on billboards suggests an attempt to appeal to the young, especially women.

In addition to the advertising blitz, the cigarette industry is active in lobbying against legislation which threatens to ban smoking in public places. If all smokers cut down by one cigarette per day, the R.J. Reynolds Co. alone would lose $92 million per year in sales.7

What is the significance of this example? It shows us one way in which our health choices are molded by forces outside our individual control; also it shows that there is a good deal of health erosion built into a free enterprise system – not because companies scheme to malign consumers, but because in a free enterprise system, increasing profits is imperative and everything else must come second, health considerations included. Often in fact profits must be pursued at the expense of health, as illustrated by advertising harmful substances and as we shall see, by avoiding expensive cleanup of hazardous working conditions or of pollution.

Advertising products and production hazards are part of a more central issue, the nature of work in capitalist society, and its impact on health. Since the fundamental task of capitalist production is to increase profits, manufacturers seek to get as much work from employees for as little wages and overhead as possible. Avoiding expensive health and safety measures is one obvious cost-saving device. The results are unsafe working conditions and a polluted environment. Another characteristic of capitalist working conditions is increasingly fragmented and alienating work, which can be extremely stressful, and lead to a variety of stress-related health problems.

A closer look at some sources of stress at the workplace (and elsewhere) and at the physical hazards of work will be the subjects of the next several sections.

Stress

Workplace stress may take many forms. It arises from several conditions, most of which may be traced to the degradation of the worker to little more than a producer of profit for someone else. Workers have little or no control over the goals of work. Nonunionized workers have little or no control over working conditions (and only about 25% of workers are organized). In addition, technological advances have historically divided jobs into more and more specialized tasks, increasingly alienating the worker from the satisfaction of overseeing a complete process. Speedup and harassment make many jobs unsafe, exhausting and irritating. And of course inadequate pay ushers in the stresses of financial insecurity, and in many cases the physical and psychological stresses of being poor.

How is a discussion of stress relevant to an understanding of social factors affecting health? The description of Joe suggested that stress led to “coping” by using drugs such as alcohol and cigarettes. But stress has more direct health effects as well, which are becoming recognized by medicine. (See box on next page). In particular, stress seems to affect heart disease and blood pressure.

Many situations other than work correlate with stress. When people are asked to list the events they perceive as most stressful, most include family break-up, death of a relative, job insecurity and job change, and migration.8 All of these events correlate to increased mortality:

- family breakup: the death rate of divorced men is two to four times higher than of married men9;

- death of a relative: Syme in a recent review of the literature on social-psychological causes of disease10 cites a study showing widows were found to have a coronary heart disease rate 67% higher than a control group;

- job insecurity: blood pressure (which is related to cardiovascular mortality because it leads to strokes), was shown in another study cited in the same review, to be associated with degree of unemployment. In one study, in the case of a plant shut-down, men who lost their jobs had higher average blood pressure than those who kept them.

All of these events appear at first glance to be very personal (as opposed to societal) occurrences, except perhaps job insecurity. But further thought suggests that they are socially influenced in very profound ways.

Family breakup for example seems the closest to an event of a very personal individual nature, at least when it refers to divorce and its effects on adults. But there are many ways in which the social context in which a marriage exists plays a role. For instance it is possible that in our society there are so few avenues to obtain emotional (not to mention financial) support or a sense of belonging, that we perhaps are overly dependent on our primary relationships. The term “‘primary”” in fact conveys the role such a relationship is expected to play. It is possible that in a society in which group particpation and concern were central, the various involvements of an individual might provide much of the fulfillment which we seek from a single intimate relationship. High and often unrealistic expectations may constitute a big stress on marriages. Another strain, not usually discussed, is simply poverty – having a family is a luxury for those who have the job opportunities such that they can support a family. This line of thought is highly speculative, but it is sure that the high rate of divorce in this country suggests there are powerful social forces stressing marriage. It would take considerable thought and study to attempt to untangle the intertwining effects of personal and societal characteristics on the instability of families, but it is surely true that marriage and divorce reflect much more than the sum of individual choices.

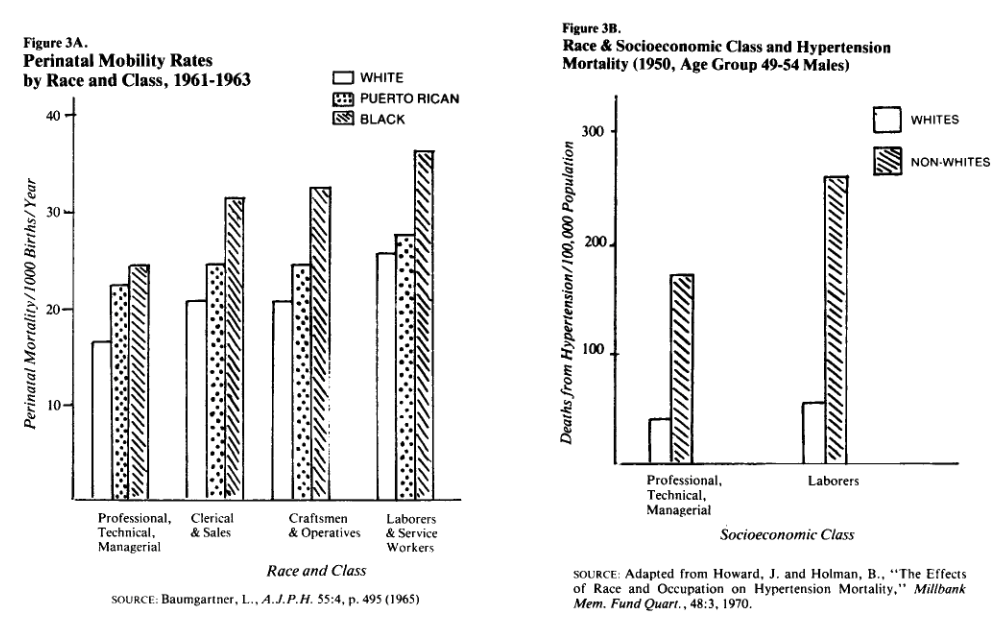

Racism is another aspect of our society which undeniably generates much stress, but which is rarely cited in the stress/disease literature. Not only does a non-white person suffer the psychological trauma of being treated as inferior and live with the threat of physical violence, but frequently also with the stresses attendant to poverty, including the most hazardous and least secure jobs.

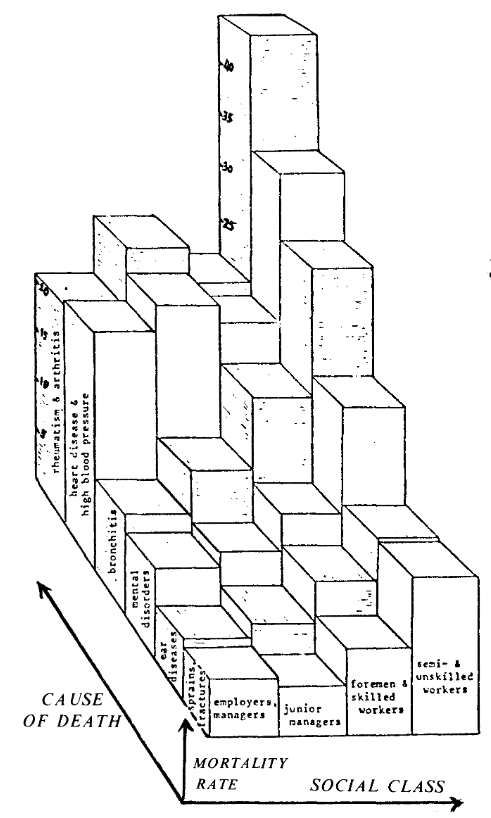

An interesting controversy surrounds the question as to whether the striking difference in blood pressure between blacks and whites is genetic or environmental (and presumably related to the stress of racism. For a thorough and unusual review article, see reference.11) If the difference is environmental, this may explain the sociological variation of hypertension among blacks, as well as the black-white difference. The 1962 National Health Survey showed that the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension for both black and white males correlates with both education and occupational status. A 1963 paper showed that there was a steady increase in hypertension-related deaths proceeding down the economic ladders from professionals to laborers (Figure 3).

We have seen evidence that social factors such as unemployment, bereavement and racism are related to cardiovascular mortality (including hypertension, stroke and heart disease). It is reasonable to speculate that in addition to these extreme situations, some general characteristics of American society are highly stressful for most people. Competition, which pervades our culture, for example, is usually described as “healthy” in America, though it is hard to see how that could be so in any physical or psychological sense. The stresses attending it can be health-destructive if they are perpetual. For disadvantaged groups, who are most likely to lose in economic competition, the primary stresses of competitiveness are compounded by the secondary stresses of frustration, anger and chronic economic insecurity.

Other stresses which are general but probably more pronounced among disadvantaged groups are those mentioned earlier as part of the alienation of work. Anyone who has worked at a job which was some combination of tedious, boring, socially useless, overly regimented, under the supervision of an oppressive person, or for the profit of someone else, can attest to the stresses of work. Needless to say, the poorer, less skilled and less educated one is, the likelier one will experience these conditions. What is being suggested here is that stress contributes heavily to ill health in the U.S. for the general population, and particularly high for minority and poor people.

|

“STRESS” – WHAT IT IS AND WHAT IT DOES Stress is a rather vague term which has been defined variously. Often it is “described as any difficult or trying situation that results in emotional pressure”12 A more biological definition has arisen largely from the work of Hans Selye, who speaks of the body’s reaction to stressful circumstances. The circumstances may be purely physical, such as pain, or psychological, such as job changes. The body’s reaction is a quite definite set of responses which are thought to be a carryover from our animal ancestors’ responses to stress. These reactions prepare the body to take some action either towards dealing with the situation headon or trying to avoid it. They have popularly been called “fight or flight” responses. Whatever behavior results, the body prepares for the necessary sudden surge of energy with a basically chemical tooling-up process. The nervous system triggers the release of several hormones, and these, together with further nerve signals, bring about such events as increased blood pressure and heart rate, and release of sugars and fats into the bloodstream to be used for energy. These changes are very rapid, occuring in seconds or minutes, and are restored to pre-stress conditions only gradually, over days or weeks. Repeated stressful situations could cause a response like blood pressure to remain at peak levels with no chance to come down. Some scientists believe that problems arise for people not only because stress may be repeated or constant, but also because our social constraints do not allow us to carry out the action of fight or flight.13 Thus tension may build without release. For example, if our debtors harrass us, we are unlikely to run away physically, much less punch them in the face. Scientists note from biochemical studies that the body systems which are involved in the physical stress response (nervous and endocrine systems) have important influences on some body functions including blood pressure, fat metabolism, salt regulation, blood clotting and heart muscle metabolism. Thus there are many plausible pathways by which stress could affect health. Retrospective studies with people have shown correlations of stress with many disease states, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, colitis and possibly cancer. Stress also decreases the effectiveness of the immune system and thus leaves one vulnerable to infection. In addition, stressful lives may lead indirectly to health problems by causing people to “cope” with drugs, including cigarettes and alcohol, with their attendent harmful effects. Research relating stress to health status remains speculative though, because stress is very hard to study. The problem is that there is no clear way to measure it. One must choose one of its resulting symptoms, such as blood pressure, or hand steadiness as an index, and none of these is related exclusively to stress, nor are any of them consistent measures of stress, even within the same individual studied over the course of time. Alternatively one can study stress using a subjective survey assessment of what situations people consider stressful and try to correlate those to health indices. Not only is stress hard to measure, but it is often one of many factors bearing on health status and hard to disentangle from other factors. Nonetheless, it is becoming increasingly recognized as an important societal factor influencing health. —Fran Conrad |

Industry and the Worker

Occupational hazards are no small threat and in general are greater for workers of low economic status. Of 100,000 work-related deaths which the Labor Dept. estimated would occur in 1976, it was expected that 14,000 would be caused by injuries, and the rest would result from sickness due to dusts, solvents, fiber gases and other chemicals.14 Even the 55,000 American deaths in the entire Vietnam War are many fewer than the deaths caused by industrial accidents alone in the same years – 114,000. During the same period, about 1 million more died from job-related disease.15

Of all the dangers to which workers are subjected the most insidious is cancer. Judging from the popular press, one might think that the connection of carcinogenic chemicals to the high rate of cancer was only recently known. A bit of probing proves otherwise. The first documented work-related cancers (among British chimney sweeps) were reported in 1775.

A man by the name of Wilhelm Heuper was employed by DuPont from 1934 to 1938. From his observations he suspected that a naphthylamine dye being used in the plant would lead to bladder cancer. Testing the chemical with dogs he confirmed his suspicions and went to management, warning that they could expect a cancer epidemic in about 20 years if they continued to use the dyes. DuPont took immediate action: they fired Heuper. The predicted cancers did occur.16 Heuper knew that the dye was not the only carcinogen around. In 1942 he wrote an 800-page book on occupational carcinogenesis, documenting all kinds of cancers in Europe and America. This book never became known to the general public.

The current cancer “epidemic” has only become widely apparent to the public in the last decade. One reason is that it was not hard to keep quiet the likely link between occupational chemicals as long as the cancers were invisibly developing. The main industries involved are those which expose workers to chemicals and particles, industries which mushroomed in the post-war boom. Since it takes about 20 years from first exposure for most cancers to become apparent, the first “crop” from the 40’s did not show up until the mid-60’s. What many scientists, bureaucrats and industrialists had long known could not remain unseen any longer.

Today occupational cancer is no hidden danger. In the industrialized world one in five deaths is from cancer.17 In addition, it is well-documented that particular cancers are associated with particular industries. Geographical clusters of deaths have spurred retrospective studies to isolate causes. Had there been prospective studies with animals, such as Heuper’s, and had the results been acted upon, an unknowable number of cancer deaths could have been prevented. Rather, industry chose to develop an arsenal of tactics to avoid spending any money on cleanup, rather than one to solve health problems. The firing of Heuper by DuPont was only an unsophisticated harbinger of what was to come.

The Chemical Coverup

A major tactic is the coverup. The asbestos industry, for example, attempted for half a century to hide evidence that asbestos is dangerous. Asbestos has long been known to cause asbestosis (lungs irreversibly damaged by the buildup of microscopic asbestos fibers) and lung cancer: more recently it was also found to cause a once rare cancer called mesothelioma, which affects the membranes of the lungs or abdominal cavity. Almost 20% of all deaths of asbestos workers are from lung cancer, and 6-7% are from mesothelioma (which is less common but always fatal). Workers in associated trades which use asbestos or simply work in an area near asbestos are also at high risk. Shipyards, for example, house a variety of trades, only some of which involve direct contact with asbestos but all of which are subject to risk. In one study in which lung X-rays were done of shipyard workers, spanning all trades, 85% showed abnormalities.18

As evidence grew about asbestos dangers, so did industry’s coverup escalate. (The history is detailed in an excellent article in Healthpac.19) In the course of the coverup, industry produced eleven studies, pretending to show how harmless the material is. The main method (according to the Healthpac article) was to test workers who had only recent limited exposure, so that the effects had not yet shown up. Just one such study cost $8 million.

Another form of coverup is misdirected health education. The American Cancer Society, for instance, is now touting a cancer education program for workers. One might expect, in view of the significant role of industrial chemicals in causing cancer, that such a program would teach workers and employers about hazards on the job. Rather it advertises that cancer education leading to early screening and monitoring can save the employer money, by decreasing hospitalization and disability expenses. Nowhere in the advertisement for the program is risk-avoidance mentioned.

Shifting the Blame

Given that the evidence against asbestos was overwhelming, the industry used another form of coverup, shifting the blame to various scapegoats including certain “bad” but atypical fibers, the bags asbestos was stored in, and most persistently, cigarette smoking.

By pointing the finger at smoking, the asbestos industry has been quite successful at shifting responsibility from industry to worker. In so doing they have also provided fuel for the lifestyle change advocates. The contribution of smoking to lung cancer, the industry points out, is much greater than of asbestos. An asbestos worker who smokes has somewhere between 7 and 90 times the risk of lung cancer as the non-smoking asbestos worker, depending on what you read.20 But what does one conclude should be done if smoking increases the risk? Should regulation and education focus on helping workers not to smoke, or on forcing industry to clean up the workplace? Any campaign to be truly effective must do both; asbestos alone is carcinogenic, and even workers’ families and people living within a quarter mile of an asbestos plant are affected. Furthermore, any stop-smoking program to be effective in reducing the asbestos risk, must not only be combined with cleanup, but must be part of a nationwide anti-tobacco campaign aimed at the production, sales and advertising of cigarettes, as discussed earlier. But the emphasis on cigarette smoking has served to hide the need to clean up the workplace, rather than to spur a 2-pronged attack.

The lung cancer/smoking link has served to obscure two facts. One, rarely brought out in the asbestos literature, is that smoking is not linked to mesothelioma.21 Mesothelioma kills less than one third as many asbestos workers as lung cancer, but it still kills and it is definitely linked to asbestos. The second fact usually obscured is that other cancers (of the rectum, stomach and colon, for example) are associated with asbestos and not with smoking.

Curiously, if one relies on the newspapers and magazines for information, one finds many articles which raise the issue of smoking and other chemical hazards; usually, it is correctly pointed out that in the cases where both are relevant, smoking is believed to be the more important factor, as in the case of asbestos-related lung cancer. It is less widely published that there are many kinds of non-smoking-related cancers. For example in a study of bladder cancer among workers in Eastern Massachusetts, it was found that 18% of all bladder cancers in men and 6% in women could be attributed to chemicals on the job. Rubber, leather, paint and organic chemical workers were all at risk. In all these cases the excess mortality was the same whether or not the worker smoked.22

Union Busting and Intimidation

Coverups have a way of holding back information until workers die or become ill in embarrassingly large numbers, causing an outcry by the appropriate union. Not surprisingly, industry then rotates its big guns towards the unions, employing various union-busting techniques. Usually union (and anti-union) campaigns are not over work hazard issues alone, but often safety is a part of the reason workers seek to unionize. A case in point is the struggle of textile workers in the south to organize against employers like J.P. Stevens. The textile industry, which has been maiming workers with brown lung for years, has put enormous sums into union-busting activities, money which could have been spent on safety.

Whether or not there is a union, outright intimidation may be employed. Workers are often harassed and/or fired for such activities as organizing health and safety committees. A particularly flagrant example was the well-publicized death of Karen Silkwood. She was killed in a suspicious auto accident on her way to give information to a New York Times reporter on safety violations concerning radiation hazards at the Kerr-McGhee plant in Oklahoma.23

Playing Poor

When the facts are out, the unions are in, and the company is up against the wall, management often resorts to cries of “We can’t afford it.” The expense of cleanup, they claim, would put them out of business or “force” them to raise their prices. In either case, they point out, the economy would be hurt. From industry’s viewpoint we are faced with a choice between the health of the economy and that of the worker. A free enterprise system pits one person’s health and life against another person’s profit.

Lobbying

Industries lobby to prevent legislation regulating hazardous substances. One of the most desperately needed forms of legislation, given the extent of chemical carcinogenesis, is laws governing toxic chemicals. No such legislation existed until 1976, thanks to the lobbying efforts of the chemical industry.24 This legislation is a step in the right direction, but it is inherently limited by its mandate to balance risk of injury against economic cost and social benefits.25

Screening

The latest industry technique of cleanup avoidance comes packaged as a form of worker protection: screening workers for susceptibility. In the asbestos industry this can take many forms, such as rating workers for “susceptibility” to lung cancer based on the amount they smoke or using newly emerging techniques which reportedly detect genetic propensity toward disease. Of course such screening procedures could be used as preventative medicine by alerting some workers to their need for more frequent medical examinations. But given industry’s record of avoidance in improving safety conditions, it is much more likely that the lists will in effect become worker blacklists in certain industries. It will be the workers’ bodies which are inspected for compliance to standards, rather than the work environment. Already some companies (such as General Motors) are refusing to hire women in their child-bearing years because of a possible risk of genetic damage to the offspring.

Industry and the Environment

Many of the same chemicals used in manufacturing make their way into products and wastes that eventually move into air, water, soil and crops, exposing all of us, albeit at slower rates. How serious are the effects of metals, pesticides, hormones (like DES) and other chemicals when inhaled or ingested?

The answer is uncertain. We do know of many instances when an accident which suddenly exposed the public to an unusually large dose of a chemical had visible and tragic consequences. The infamous air pollution disasters of Donora, Ponna, and the Meuse Valley led to many deaths among people with respiratory ailments: the recent leakage of waste chemicals that had been buried near Niagra Falls has resulted in a doubling of births requiring Caesarian sections. But what of the small amounts of chemicals to which we are all exposed daily? How is one to trace an illness back to one or more of all the known (and unknown) exposures one has undergone in a lifetime? Data must be epidemiologic; that is, disease rates must be correlated with local environmental or biological factors. However, such data can never be conclusive, only suggestive, because of the multitude of inseparable and hard-to-measure factors. But if unregulated or inadequately regulated chemicals continue to be incorporated into the environment, we will likely see an accelerating number of chemical disasters and a continuing increase in cancer incidence.

Role of the Government in Occupational Safety

The government role has varied from out and out complicity with industry to attempts at regulation. But even those regulations which exist have been emasculated before becoming law by capitulation to industry pressure.

One of the biggest breakthroughs for worker safety was the creation of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in 1970. But not only has it employed laughably small penalties (maximum penalty $1000 per violation; average penalty $30 per violation),26 it has been so underfunded that its rules have been almost unenforced. For example in a study done of enforcement of asbestos standards in Connecticut in 1974, it was found that there was only one industrial hygienist in the entire Connecticut-Western Massachusetts region, and the several safety inspectors were not trained in industrial hygiene. Even if there had been sufficient staff, the study points out, there were no accessible medical facilities to comply with OSHA medical examination requirements.27

Not only does OSHA lack the apparatus and funds to put teeth into its regulations, but it is also under seige by industry (frequently with the help of the courts). OSHA procedures are such that industry can buy time and win reprieves by taking to court every citation of a violation and every standard that OSHA promulgates. The courts have severely eroded many OSHA provisions. For example, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals threw out a standard for benzene on the highly dubious grounds that OSHA did not quantify exactly how many lives would be saved by the standard despite clear evidence that benzene causes cancer.28 Similarly the OSHA provision that workers can walk off the job without fear of reprisal when faced with a severe imminent hazard, was virtually wiped out by the same court.29

Given that regulation threatens industry with enormous potential expense, it is not surprising that industry will do all it can to weaken OSHA.

One of the more progressive proposals currently being considered by OSHA is a generic cancer standard.

This means that chemicals would be classified as known or potential carcinogens and restricted as such. It would eliminate the overwhelming burden OSHA now has of definitively proving each chemical carcinogenic on a case by case basis. Such a proposal, if implemented would restrict thousands of chemicals now in use and thus is potentially very expensive to industry.

In fact according to a recent article,

Some 120 companies and 60 trade associations have banded together to form the American Industrial Health Council, with the expressed purpose of combating (OSHA’s proposed generic cancer standards) … Carter’s Regulatory Analysis Review Group, chaired by Council of Economic Advisors chairman Charles Schultze, selected the generic carcinogen policy as one of the handful of very expensive regulations it would study in 1978. . . . The review group recommended, as did industry, that OSHA pay closer attention to the costs as well as the benefits of proposed regulations.30

Probably the most knowing witness to the government’s role is Wilhelm Heuper, the same epidemiologist who documented occupational carcinogenesis and who was fired by Dupont. Heuper became head of the Environmental Cancer section of the National Cancer Institute. One of his concerns was the high rate of cancer among chromate miners. The chromate industry became nervous when Heuper began speaking out on the hazards, and put pressure on the government to quiet him. The Surgeon General in 1952 actually forabde Heuper to share any evidence with state Departments of Health and forced him to stop all epidemiological studies. Because of this and other government surpression and inaction, as Heuper later pointed out, for the crucial decades following World War II there were no records kept in the United States of worker exposure and cancer rates. As was mentioned earlier it took the later rash of cancer deaths to spur retrospective studies, seeking to do what prospective ones could have done better 10 years before.31

The ambiguous role of government in setting safety standards too few and too late, and in crippling enforcement, is a reflection of the general role of government in this society. For though it is in some ways responsive to public needs and certainly employs some dedicated advocates, its role really amounts to little more than legitimization, and is curtailed by more powerful interests. The real clout is in the hands of capitalists. An article on OSHA regulation states,

. . . in instances where carcinogenic hazards to workers of a chemical is established, the overriding consideration of the employer must be whether he can remain competitive in a situation in which costly engineering controls . . . (are) required by stringent regulation.32

Along the same lines, a Carter administration official said, “it is important to ensure that any new regulations do not impose unnecessary and uneconomic costs on American industry.”33 In short, the regulatory agencies should be the protectors of the common people, but they exist within a government which is the protector of industry. Should the interests of the two conflict, it is not hard to see which sector is favored by legislation and the courts.

Class, Race and Health

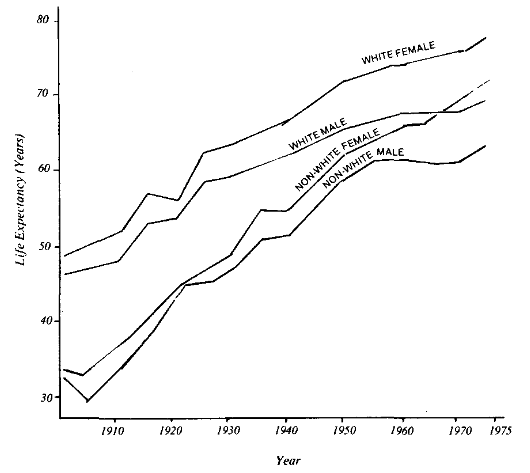

For all the factors which have been discussed which erode health, such as stress and job hazards, one might expect the impact to be greater for the poor and minorities. If we look at mortality (or life expectancy, which is calculated from mortality rates), a common index of health status, we find in fact clear class and race correlations. Life expectancy has historically been higher for whites than non-whites in the U.S. (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the black-white gap in mortality closed by 1975 (Table 1) if one looks at the figures combined for both sexes. Figure 5 suggests that the improvement in life expectancy for black women is responsible; there is still a large gap between black men and white men.

Similarly there is a difference in mortality depending on one’s socio-economic status. David Jenkins and coworkers did a study in the Boston area which showed what they called “zones of excess mortality.”34 They compared the mortality rates in two Mental Health Catchment areas. An upper-middle class area showed a mortality rate which was 81% as great as the Massachusetts rate. A poor area had a mortality rate of 128% as great as the state rate. A similar study in three American cities calculated an index of excess mortality due to socioeconomic differences. Not only did mortality correlate with socioeconomic status, but the inequality measured by the index increased between 1960 and 1970 (Table II). Their study interpreted this and other data to mean,

. . . improvements in the health of our nation seem to benefit the higher socioeconomic groups and health deterioration to tax the lower socioeconomic groups.35

What we see is that the chance of dying is greater among non-white than white, and greater among poor than rich. The trend is improving by one index (overall race differences in life expectancy) but worsening by another (socioeconomic differences in mortality).

Table 1.

| Mortality Rates in the United States by Race | ||

| Deaths per 100,000 populations | ||

| Year | white | black |

| 1972 | 95 | 97 |

| 1973 | 94 | 97 |

| 1974 | 92 | 92 |

| 1975 | 90 | 89 |

| SOURCE: Health in the U.S. Chartbook, 1976-1977 DHEW (HRA). | ||

What factors account for the class and race health differences? We have already discussed stress and hazards of work as factors, and touched on the effects of stress-coping drugs and nutritional status. Another factor is living conditions. Urban studies of health variables using census and agency data have shown that dilapidated housing correlates with tuberculosis and suicide. In general poor neighborhoods have poorer trash collection and often infestation by insects and rodents. Furthermore diseases which flourish in such conditions are most likely to spread in overcrowded living quarters. The National Health Survey of 1969-1971 found that crowding, defined in terms of number of people per room, correlates with common infectious diseases of childhood, with adult pneumonia and tuberculosis, with disability due to illness, and with disability from home accidents.36 Crowding is also well-known as a stressful condition; the stresses of poverty in general, and crowding in particular, put mental as well as physical health at risk.

A third factor is unequal accessibility of health care. Table 3 illustrates a race difference in hospital usage by children in 1964 as an example. There has been some catch-up in accessibility since medicaid and medicare were introduced. But even in 1974, when a large percent of people were covered by government insurance, 40.2% of people under 65 were uninsured because insurance was too expensive.37

Access to health care, though important once there is a health disorder, should not be overestimated as a contributor to the health status of a population, as measured by mortality. It contributes little toward prevention of illness or maintenance of health.

If medical care had much effect on overall health, one would expect that equalizing access to health care facilities would wipe out class differences in health. But in England after 30 years of universal free health care, the class differences remain in health as they do in the society in general (Figure 6).38

In looking at how life and work in capitalist society affect health, the class nature of health emerges. We can go further than illustrating the class and race differentials in health status, and point out that health reflects the level of class struggle at any moment. Health of workers always involves expense to capitalists, and as such it is an object of struggle. (It also is the object of conflicts within the capitalist class, as certain sectors profit from the health care industry.) But overall worker health is a privilege which must be won, and the degree to which it is won and maintained reflects the strength of working class struggles. Historically, for example, improved working conditions and shorter working hours constituted the hard won gains of a growing labor movement. Currently, regulatory legislation on occupations and environmental health may be seen as the gains of a strong labor movement, but the hot battle against regulation reflects the urgency with which capitalists seek to head off threats to profit in a time of economic crisis. In the balance of the struggle around regulation lie the health and lives of millions. A second example of current struggle is the trend toward cutbacks in government spending on health. Cutbacks can be expected to increase as the tax revolt grows, illustrating that capital can afford less and less human services. What services people manage to retain will be a measure of the strength of workers.

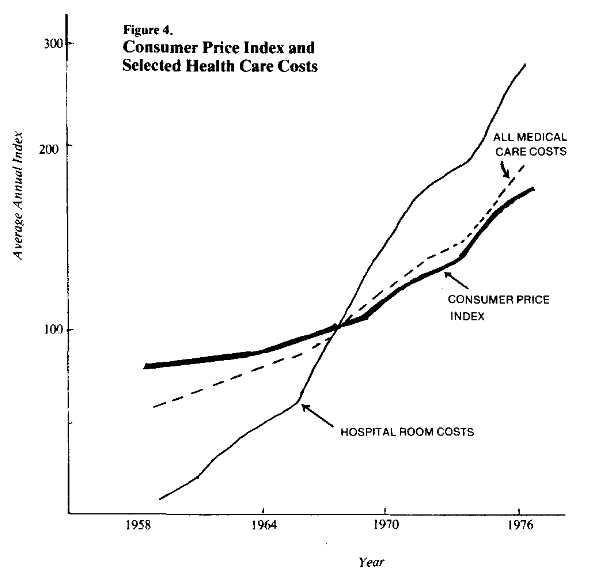

In this context the “lifestyle” movement can be seen for what it really is. Capital is threatened by the skyrocketing cost of health care (which is increasing faster than the overall rate of inflation – see Figure 4). At the same time the increase in chronic diseases such as heart disease and cancer is not being slowed by the massive expenditure on curative medicine. To the industrial employer, chronic disease means long expensive hospitalization, high insurance premiums (the bulk of which are paid by the employer) and days lost from work. It is this situation, rather than an altruistic concern for health, which is behind the current movement for health education toward lifestyle change. Unfortunately it is a misguided movement which will have no impact other than propaganda value, and will probably fade away in a few years. The real battles for health are in the arenas of class struggle. What is needed are advances in unity and strength of workers and growth in awareness that private enterprise itself is the problem. In the short run, such advances may be focused on reform, such as a national health service or strengthened regulatory laws. But in the long run the overthrow of the capitalist system is the only step which can put health ahead of profit.

Table 2.

| Increase in Excess Mortality due to Socioeconomic Status in Three Cities | ||

| 1960 | 1970 | |

| Birmingham | 5.7 | 10.3 |

| Buffalo | 7.15 | 9.5 |

| Indianapolis | 19.5 | 23.0 |

| SOURCE: See note.39 | ||

Table 3.

| Number of Children Hospitalized, by Race and Family Income | ||||

| Age under 15 years, with one or more episode per 1,000 population per year. Percentage having a total stay of 1-7 days, United States, 1968. | ||||

| Hospitalization rate | Percentage with stay 1-7 days | |||

| Income | white | non-white | white | non-white |

| Under $3000 | 65 | 38 | 72.7 | 59.1 |

| $3000-$4999 | 59 | 36 | 79.5 | 69.9 |

| $5000-$6999 | 53 | 38 | 82.3 | 59.5 |

| $7000-$9999 | 57 | 44 | 84,3 | 69.4 |

| $10,000 and over | 48 | 44 | 84.4 | 61.1 |

| SOURCE: U.S. Public Health Service | ||||

Where Do We Go From Here?

What kinds of actions around health can help build class struggle?

- Health educators can continue to help individuals change habits, but with a perspective that clarifies rather than obscures the limitations of individual change, and shows people they are not to blame for health behavior. Perhaps such an approach would allow a sense of social outrage to be a motivating factor; but more important, health educators must teach the need for social change and seek avenues of struggle at the local level. For example, neighborhood residents can demand and fight against pollution.

- People can fight for increased funding of the existing environmental, OSHA and toxic chemical laws, but again, not without realizing that this legislation is only a stop-gap measure as the system of private profit remains intact.

- People can continue to struggle for tougher national environmental standards and occupational safety standards. All advances which have occurred so far have been the result of public or union pressure.

- People can fight in the courts for redress of illness due to past unhealthful workplaces. If enough cases are won requiring monetary retribution, industry may even do some cleaning up.

- At the workplace, workers can continue to form health and safety committees within their unions, and form unions where they are unorganized.

- People can pressure the media to employ healthful messages and the Federal Communications Commission to require counter-advertising of harmful products.

These struggles require long range united actions. They may begin to result in improvements in health, but they will not change the manufacturing and advertising of dangerous consumables, nor will they change the basic priorities of the society. The only way that health will become more important than profit is by throwing out the system which is the slave of profits. Ultimately, that is the task of the worker, the consumer, and the health educator.

Fran Conrad is a longstanding member of Science for the People. She has taught biology and science & society courses in high school, and has been involved in community health education. She is now pursuing a career in occupational health.

>> Back to Vol. 11, No. 2 <<

NOTES

- Wechsler, H., and Gottleib, N., eds, Health Thyself, Blue Cross of Massachusetts, Inc. and the Medical Foundation, Inc., p. 2.

- Knowles, J ., “The Responsibility of the Individual”, Daedalus. special issue on health care, “Doing Better but Feeling Worse”, Winter 1977, p. 59.

- Work in America, Report of a Special Task Force to the Secretary of HEW, M.I.T. Press 1973, p. 79.

- Federal Trade Commission Report to Congress: Pursuant to the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act. 1976. Part I Report to Congress (1977).

- The summary of the activities of the F.C.C. is from Roberts, C. D., “A Summary of Federal Communications Commission Activities, Dealing with Cigarette Advertising on Both Radio and Television,” in Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference on Smoking and Health. Vol. II, DHEW, 1975, p. 415ff.

- The summary of the activities of the F.C.C. is from Roberts, C. D., “A Summary of Federal Communications Commission Activities, Dealing with Cigarette Advertising on Both Radio and Television,” in Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference on Smoking and Health. Vol. II, DHEW, 1975, p. 415ff.

- According to R.J. Reynolds Co. President, William D. Hobbs, quoted in Consumer Reports, Aug. 1978.

- Several references are cited in Eyer, J. and Sterling, P., “StressRelated Mortality and Social Organization”, The Review of Radical Political Economics, special edition, The Political Economy of Health, Vol. 9 No. I, spring, 1977, published by the Union for Radical Political Economics, N.Y., especially “Economy in Crisis” in Dollars and Sense, July/ Aug., 1978, p. 5.

- Parkes, C., Benjamin, B. and Fitzgerald, R., “Broken Heart: A Statistical Study of Increased Mortality Among Widowers,” Brit. Med. J., I :740-743, 1969, cited in Syme (ref. 9A).

- Syme, S., “Social and Psychological Risk Factors in Coronary Heart Disease,” Modern Concepts of Cardiovascular Disease, Vol. XLIV, No.4, April 1975.

- “Hypertension and Racism”, Progressive Labor Magazine Vol. 9:4, March-April 1974.

- Fitch, K. and Johnson, P., Human Life Science, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977, p. 476.

- General description of the fight or flight response is summarized from Eyer and Sterling (see Parkes, C., Benjamin, B. and Fitzgerald, R., “Broken Heart: A Statistical Study of Increased Mortality Among Widowers,” Brit. Med. J., I :740-743, 1969, cited in Syme (ref. 9A).).

- Figures are cited in Turner, Steve, “Work can be Dangerous to your Health”, Boston Globe, New England Magazine, May 2, 1976.

- Some good general reviews of occupational hazards include: Eckholm, E., “Unhealthy Jobs”, Environment 19:6, Aug/Sept. 1977: Eckholm, E., The Picture of Health, N.Y.: Norton and Co., Inc., 1977; ref. cited in note ll; several article on Occupational Health and ty in Science for the People, VII:5, Sept. 1975; Epstein, S., “The Political and Economic Basis of Cancer”, Tech. Rev. July/Aug. 1976; for particular substances see the Healthpac publication, and Survival Kit. published by Mass. COSH, 120 Boylston St., Boston, MA 02116.

- Agran, L., The Cancer Connection, Houghton-Mifflin, 1977.

- Eckholm, E., The Picture of Health, N.Y., Norton and Co., Inc., l977, p.89.

- “Asbestos-Associated Diseases in U.S. Shipyards”, CA – A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 28:2 Mar/ April 78, pp. 87-89.

- Kotelchuck, David, “Asbestos Research: Winning the Battle but Losing the War,” Healthpac Bulletin No. 16, Nov/Dec. 1974, and Kotelchuck, “Asbestos, Science for Sale”, Science for the People VII: 5, Sept. 1975.

- According to a Physician’s Advisory from DHEW called “Health Effects of Asbestos”, April25, 1978, the increased risk is 7.5-30 times; according to Selikoff, 1., et al., it is 92 times, in “Asbestos Exposure, Smoking and Neoplasia,” JAMA, 204:2, April 8, 1968.

- Cancer and the Worker, New York Academy of Science, 1977, p.44.

- Cole, P. et. al., “Occupation and Cancer of the Lower Urinary Tract,” Cancer, 29, May 1972.

- Supporters of Silkwood Newsletter, #5, May 1978.

- Epstein, S., “The Political and Economic Basis of Cancer”, Tech Review, July/Aug. 1976.

- Public Law 94-496.

- Draft of How to Use OSHA: A Guide for Workers, by the Occupational Safety and Health Project, Urban Planning Aid, Boston, MA 1974.

- Schoenberg, J. and Mitchell, C., “Implementation of the Federal Asbestos Standard in Connecticut,” J. Occ. Med. 16:12, Dec. 1974.

- The American Petroleum Institute et al vs. OSHA, et al, U.S. Court of Appeals, 5th Circuit, Oct. 5, 1978.

- Marshall & Daniel Construction Co., Inc. vs OSHA 1031, 1977.

- Clark, Timothy, “Cracking Down on the Causes of Cancer,” National Journal, 12/30/78.

- Agran, L., The Cancer Connection, Houghton-Mifflin, 1977.

- Lassiter, D., “Case Study 3: Vinyl Chloride – Best Available Technology”, in Occupational Carcinogenisis. Wagoner, eds, N.Y. Academy of Science, 271:1-516, 1976.

- “Economy in Crisis” in Dollars and Sense, July/ Aug., 1978, p. 5.

- Jenkins, D., et. al., “Zon,es of Excess Mortality in Massachusetts,” NEJM 296: 1354-1356, June 9, 1977.

- Yeracarios, C. and Kim, J., “Socioeconomic Differentials in Selected Causes of Death”, AJPH, 68:4, April 1978.

- All data are from a review article, Kasl, S., “Effects of the Residential Environment on Health and Behavior,” a review in Hinkle, L. and Loring, W., eds, The Effect of the Man-Made Environment on Health and Behavior, DHEW, 1977.

- Health in the U.S. Chartbook 1976-77, DHEW (HRA) 1977.

- Health Group Collective, “The Social Production of Ill-Health” Science for the People, No. 38, Winter 1977-78.

- Yeracarios, C. and Kim, J., “Socioeconomic Differentials in Selected Causes of Death”, AJPH, 68:4, April 1978.