This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The False Promise: Professionalism in Nursing

by the Boston Nurses’ Group

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 10, No. 4, July/August 1978, p. 23–33

Nurses Are Just Beginning

The organizing done by nurses in the last few years shows that we are learning from the examples set by service and technical workers. We will use the same tactics as they do. But our organizing experience has been held back by the influence of the professional associations. Nurses have yet to recognize that these tactics are most effective when carried out with the combined forces of all the hospital workers organized into the same union.

Unions will not solve all our problems. They have traditionally concentrated on economic issues, and have been reluctant to challenge “management rights” at the workplace. Unfortunately, management rights include the right to control the working and patient care conditions we would often most like to change. Unions usually do not involve themselves in issues such as community control of hospitals, or the quality of health care delivered. These are things that we will have to aim for. But without the basic protection that unions bring, and the increased strength they provide to workers, we could not even begin to think about these long-range goals.

WHAT KEEPS US DIVIDED?

When hospital workers begin to organize themselves, management tries very hard to prevent them from succeeding. They exploit existing divisions in the workforce and try to create new tensions among workers. With so much of the money and resources in their control, they are sometimes able to keep unions out. This has been especially true in Boston.

Union-Busting by Hospitals

Their methods have been varied. For example, the Melnick, Mickus, and McKeown Corporation is a Chicago-based consulting firm which helps hospitals fight unions. In 1973, the New England Medical Center Hospital in Boston paid them to engineer an anti-union campaign. In 1974, the Beth Israel Hospital also hired them. Hospitals are willing to pay large amounts of money to defeat a union drive: Melnick makes about $500 per day for each consultant on the job, in campaigns that can go on for months.1 In 1975 St. Elizabeth’s Hospital hired Walter Grace, an experienced unionfighting administrator, and made him director of nursing during the workers’ campaign for unionization there. In 1976, Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge held a two-day seminar for all department heads and administrators, run by another Chicago consulting firm, Holloway, Hecht, Hacker, Belder, Inc. The subject: how to keep unions out. These are all examples of how people who run hospitals are more than willing to use their money to maintain control over what happens in their hospitals. Their tactics were an important factor in defeating union drives in these hospitals.

People hired to fight unions are given a free hand in the hospital to do things which union organizers aren’t allowed to do. They can meet different individuals and groups of employees on hospital property and hospital time, they can post anti-union leaflets and can buy off workers with promises of raises and better working conditions. They have money, are organized and do their job well.

However hospitals don’t just persuade people not to vote for unions. They also intimidate people, using such illegal tactics as threats and firings. The National Labor Relations Board has ruled that the New England Medical Center Hospital must rehire an active union organizer who was fired in the midst of a campaign there. They have also found St. Elizabeth’s and Otis Hospital guilty of unfair labor practices in connection with their union campaigns and ordered new elections. Hospitals know when they are engaging in illegal activities, but also know that fighting in the courts is a drain on union drives and interrupts the momentum of organizing. And that’s more important to them than obeying the law.

Divisions by Department

In their attempts to keep unions out, management tries to undermine people’s shared interests and to stress divisions in the workforce. Divisions start with the way hospital work is so compartmentalized, with housekeeping and dietary and maintenance and transport and nursing and lab. The list could go on and on. Yet how often do we feel that we are working together with other departments? More often housekeeping is angry at nursing for running over their newly washed floors, while nursing is angry at dietary for not bringing the trays up quickly enough, while X-ray is angry at transport for not getting patients down on time while transport is angry at everyone who wants them to be in 20 places at once. Too often nurses think that we are the only ones who are understaffed and overworked. But because this is true for everyone, we have little time to get to know and understand the jobs and working conditions of others in the hospital. Nor is there any priority put on this understanding, beyond knowing whom to call if you want to get something done, or to complain because it hasn’t been.

However, it is not just our jobs that keep us apart. We live in a society where people are divided by race, class, sex, ethnic background. Just as it’s a myth that America is a melting pot where everyone is equal, it is a myth that we in the hospital are just one big happy family.

COMPARING NUMBERS OF WHITE & MINORITY WORKERS IN DIFFERENT LEVELS OF HOSPITAL JOBS

| Peter Bent Brigham | Peter Bent Brigham | Beth Israel | Beth Israel | University | University | Mass. General | Mass. General | |

| % White | % Minority | % White | % Minority | % White | % Minority | % White | % Minority | |

| White Collar Professional | 93.3 | 6.7 | 91.8 | 8.2 | 90.5 | 9.5 | 96.3 | 3.7 |

| Service Workers | 42.9 | 57.1 | 35.3 | 64.7 | 17.6 | 82.4 | 48.8 | 51.2 |

Source: 1974 Equal Enployment Office Report—1 (available the public at every hospital receiving federal funds).

Divisions by Race

The myth is particularly clear when we look at racial divisions in hospitals. The distrust between black people and white people which is such a familiar part of our society takes its toll within the hospital, just as it does everywhere else. In the hospital, blacks and whites work alongside each other—but most frequently in different departments or different level positions so that there is little chance-to really get to know one another.

In Boston, most RNs are white. There are more black nurses in LPN positions than in RN positions, and still more blacks in aide positions. This means that blacks and whites do not deal with each other on an equal footing, and it encourages the “let’s keep separate” attitude of professionalism.

Black workers are consistently concentrated in the lower-paying jobs in the service and labor sector where there is little chance for advancement. (See box.) This reflects the general position of black people in this society.

As white working class people know very well, there are plenty of white workers in the lower-paying jobs at every hospital. By and large, whites don’t have much chance to advance from these jobs either. In reality, they put up with similar working conditions and have the same interest in change as do their fellow black workers.

But many white people still want to believe that they—or maybe their children—can move up to the middle class. For black people, it is easier to see that they aren’t moving anywhere, and this has often led to increased determination on the part of black workers to fight for improved job conditions.

In New York City, for example, where the service and labor departments of hospitals are overwhelmingly black, there was a massive union drive throughout the city during the 1960’s, at the same time that black people everywhere were struggling for equal rights through the civil rights movement. Today New York hospitals are union hospitals, with a dramatic increase in benefits.

This trend is also apparent in Boston, where University Hospital and Jewish Memorial Hospital, which both have predominantly black service departments, have been unionized by Local 1199, while union drives in several other Boston hospitals have failed.

These examples point to the influence black workers have had in improving working conditions through unionization. When the strengths of black and white workers are combined, the workforce will benefit even more.

In talking about racial divisions, another point is important. In Boston, there are various non-English speaking ethnic groups. Language and cultural barriers a_re ~ form of dividing line which can also be very effective m separating one group of workers from another. At O~is Hospital in Cambridge, one of the major problems Ill the union drive was the lack of communication between English-speaking workers and those from Portuguese and other ethnic backgrounds. The different groups tended to keep to themselves and this made it more difficult to get out information about the union. The administration used the threat of deportation to intimidate foreign-born workers at the time of the union election, and in fact, actual immigration raids were carried out which made workers even more afraid to exercise their right to vote.

Racial divisions work to the advantage of management, and against the best interests of hospital workers. They keep the workforce divided among itself, and hold back the struggle for change. Much of the time, administrators don’t have to do anything in particular to create racial divisions: the tensions produced outside the hospital (by people’s experiences in housing, jobs, or education) run their course to reproduce the same tensions inside the hospital. At other times, management actively promotes racism by means of policies which increase racial and ethnic tensions (such as deliberately assigning workers to different departments on the basis of ethnic background, or by making promotions based on race).

Administrators are not likely to do anything to improve cooperation and communication among various racial groups. It is up to us to achieve this, and every step we take in this direction will work to our advantage.

Divisions by Sex

Another way that workers are divided is by sex. Many women hospital workers, including nurses, are aware of how sexist attitudes at work affect us as individuals. Sexism towards female hospital workers is no longer as blatant as it once was, but it is just as strong in subtle ways. A nurse is no longer forced to show respect for doctors by giving her chair to any doctor who enters the room. Instead, doctors show their lack of respect for us by hugs, squeezes, and fake come-ons, thus maintaining the unequal relationship. Doctors on rounds make us feel like we’re completely invisible (just as nurses often treat other hospital workers as if they didn’t exist). And, although women make up 80% of health care workers2, we are often made to feel stupid or unimportant; men (especially doctors) usually have little respect for our judgment. Whenever we make a wrong decision, we are reprimanded by doctors; when it is right, someone else gets the credit. After a while, even we don’t believe in our own abilities—and this includes our ability to organize for better working conditions.

Sexism affects us every day as individuals. It also acts in a variety of ways to divide the workforce along male/female lines. For example, although there are few male nurses, they are often promoted to higher positions much faster than a female nurse would be. This creates a division between men and women because female nurses resent men’s special treatment. Hospital departments, such as building service and housekeeping, are often mostly male or mostly female. Even when men and women are in the same department, they perform different jobs. This reflects the traditional attitude that some work is women’s work and some is men’s. Our employers take advantage of this attitude to create another division in the workforce.

Where men and women do have similar jobs, they often see each other as competitors for the small number of available positions. Women are frequently paid less than men for doing the same job. When this happens, male workers suffer too, because the employer will try to pay everyone the lowest wage he can get away with. If he can pay a woman less, why should he hire a man? Male workers thus end up thinking that female workers are a threat to their jobs and to the level of their wages, instead of seeing. that the real threat is the administration’s unfair wage or promotion policies which make one group of workers compete with another group.

Obviously, divisions such as these weaken us by splitting the workforce into smaller groups. However, we can overcome these divisions. For example, male workers can support bringing women’s wages up to the level of men’s. Then management will not be able to use lower wages for women as a way of keeping everyone’s pay down. In order to overcome divisions by sex, men and women will have to support each other’s demands in order to increase our unity and improve the conditions of the workforce as a whole.

Divisions by Class

It is easy to see differences within the workforce besides sexual and racial ones. Varying levels of education and income, varying lifestyles, along with doing different kinds of work, are all factors that influence how we see ourselves and others. These factors make us feel that there are more differences than common interests between people who work in the same institution. There is so much hierarchy—so many job categories, so many levels of pay, respect, and seeming importance—that it is hard to see whom we have what in common with.

But one very basic thing we all have in common is that we all depend on the hospital administration for our jobs. It is the administration and the more powerful doctors that control our work conditions and livelihood. They depend on us to get the work done; we depend on them to provide our jobs.

This relationship between hospital administrators and hospital workers is no different from the situation in any other industry in the country. It is an economic relationship between two classes of people. One class owns and controls all the factories, hospitals, corporations, banks, mines, etc. The owners depend on members of another class, the working class, for doing the work that creates their profits (in health care, as we talked about before, the profits may be indirect, or might be seen as high salaries or as power within an institution). Since the workers don’t own the banks, hospitals, etc., they have to depend on the owners for the jobs and wages needed to live.

It is important to look at this economic class relationship when we are deciding who in the hospital shares our interests. Otherwise, the smaller differences among us in terms of education or lifestyle will seem more significant than they really are. Not that these differences aren’t real; we need to be aware of them so that we can solve problems that various parts of the workforce might have in organizing together. But it is when we compare the hospital administration to the workforce as a whole, that we can see a difference that is really significant. This is because it is a class difference between those who do the work and those who benefit economically from our doing it. In comparison with this dividing line, rhe differences within the workforce are far less important.

It is true that people in lower management positions do not really own or control the hospital, and yet they do not share our interests. Supervisors, for example, are not necessarily in the same economic class as administrators. The same is true of head nurses: many come from the same class as their staff. But the important thing is that they carry out the policies of the administration and identify with the management’s interests: budgeting, controlling workers, prestige, profits—rather than with the interests of the workforce: better pay and working conditions, better patient care, more control over our jobs.

What about staff nurses? Nurses today come from many different backgrounds and many different levels of education. A nurse may or may not come from the same economic background as a housekeeper or transport worker—but again, the important thing is that we have the same interests. We can identify with them because we are all part of the hospital workforce.

Racism, sexism, and “class” differences, can all work hand in hand. We need to be aware of the effects of them all together. For example, what happens when nurses are aware of discrimination against women, but don’t think about where our class interests lie? We end up trying to improve our position as women by moving up. We forget that there is only space for a few at the top, and that in any case it will not improve the conditions of male or female workers if women are the administrators instead of men. If a few women move up the hierarchy, it will not really change the overall picture. Yet this is the kind of thinking that professionalism encourages: one group of people trying to pull themselves up at the expense of another group. We won’t make any long-term progress this way.

Professionalism goes along with class attitudes, too. For example, some RNs are starting to move up the ladder by becoming practitioners or specialists. Obviously, not everyone can move up. Nevertheless, professionalism would like us to think of ourselves as “upwardly mobile”. In this way, it encourages us to identify with a different class of people, trying to make us feel more like doctors and less like all the people we work with. Another way to say this is that professionalism encourages nurses to take on the attitudes of a class to which we do not belong.

* We realize that while some head nurses are mainly sympathetic to the administration, others are interested in improving patient care and improving the jobs of their staff nurses. But, unfortunately, when administration policies are to be carried out, the head nurse must be an administrator or else she won’t be head nurse. And for many head nurses, identifying with the administration is the most important factor in getting the job in the first place.

Professionalism Keeps Us Apart, Too

Looking at all the unnecessary divisions that are set up in the hospital workforce, it shouldn’t be surprising that management can tell nurses, and that we can really feel, that we don’t belong in a union or organization with other workers in the hospital. We are constantly encouraged to think about the unique position of nursing—to think of ourselves as professionals.

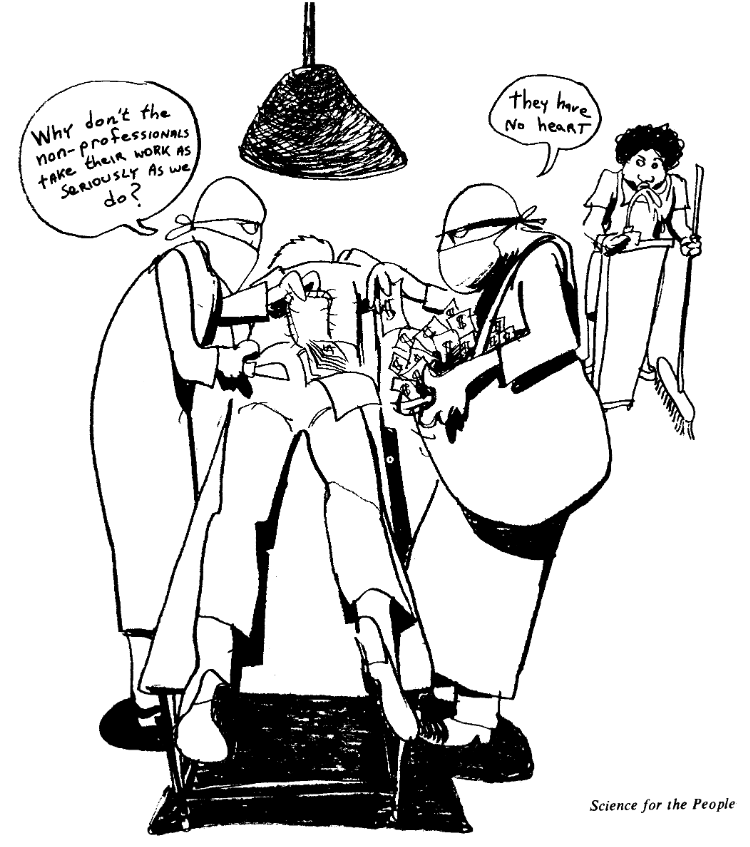

Why do hospitals want us to see ourselves as separate from other hospital workers? Again, it is a case of divide and conquer. Professionalism divides the workforce in the hospitals, just as do differences in sex, class, and race. This allows hospital administrators. to have free reign in determining the conditions under which we all work. One group of workers (nurses) is played off against another group (service and technical).

Professionalism teaches us to look down on other workers, especially service and technical workers who are “below” us in the hospital hierarchy. These feelings most often come into play in our relationships with nursing assistants, dietary workers, housekeepers and transportation workers, that is, the people with whom we work most directly.

Many nurses feel that nursing school makes us qualitatively different from, or better than, other workers. We receive formal training (though most of us agree that it could be a lot better), and we are highly skilled. But knowledge and skills are not only learned in school. Just ask any new grad. We have to recognize that many people, particularly aides, have worked in the hospital for years, and have learned many things through experience and practical application. Although not learned in a classroom, this knowledge is as valid as ours.

There is another false distinction found in many, work situations. That is the separation between people who earn a living with their heads and those who do it with their hands. Nurses feel superior, as do almost all workers who consider themselves professionals, to other workers whose jobs involve manual labor. For nurses this makes no sense at all, since much of the work we do is manual labor. Some of our work does require planning, analysis, and thought, but that doesn’t make us better than other workers.

So these are some of the attitudes that nurses have about other hospital workers. Do we benefit from these attitudes? What do we gain from this superiority towards and separation from other hospital workers? The people who run the hospital—as opposed to the people who do the work—would like us to think that we do benefit. We do receive better material benefits than do many hospital employees, but the rhetoric of professionalism should not make us lose sight of the fact that we have no real control over our job situation. The fact is that we are workers—skilled workers—and we should be proud of it.

Hospital administrators and the nursing office would like us to believe that bad patient care is caused by those “below” us, rather than be inefficient and wasteful hospital bureaucracy. They want us to think that dietary workers are stupid, housekeepers are lazy and aides don’t care. All this is to divert our attention from what is really going on: a health care system that benefits neither the patients nor the workers, the goals. of which are to increase profits and prestige for a select few. The blame for bad health care is put everywhere but where it belongs.

WHAT IS WRONG WITH OUR SYSTEM?

We have shown that the health care industry in this country is for profit and not for people. There is a multimillion dollar business that surrounds hospitals—drugs, equipment, high salaries for doctors and administrators, real estate for hospital expansion and more.

Although there wouldn’t be such an industry without patients, consumers are not allowed to have much say in decisions that affect their health care. Given the choice, for instance, most people would place a higher priority on preventive health care, including screening programs, more accessible local clinics and so on. However, even with more preventive care, we would still be faced with serious health hazards due to working conditions in our industries and pollution in our environment. We have to ask the question: why do people get sick?

Violence is done to people every day in factories, hospitals, mines, fields, on construction sites—in the form of dangerous working conditions. The best doctors, nurses and hospitals will not prevent a miner in West Virginia from getting black lung disease, nor a worker in a cotton mill from getting brown lung disease (byssinosis). The most available health care will not prevent asbestosis or paralysis from insecticides or severed limbs from unsafe machinery. Even the health care institutions themselves are hazardous to their workers: back injuries, increased x-ray exposure, stress from rotating shifts, increased incidence of spontaneous abortions and liver tumors from exposure to anesthetics.3 A more insidious violence is waged against all of us every day in the form of poor nutrition: some people lack the bare necessities, while the food available to others contains chemical additives and poisons. Society as a whole is endangered by oil spills in our oceans and potential disasters at nuclear power plants. The most caring, competent specialist or surgeon cannot prevent cancer caused by the poisons we breathe and ingest every day.

Many of these diseases are preventable and it is important to ask why such known hazards are allowed to continue. Part of the answer is that workers and consumers are not given a choice about safer workplaces or good food. Even though a worker may be directly affected by a high level of toxic fumes, or a consumer by food full of hormones, preservatives and insecticides—the person who decides to let these dangers persist is the owner of the factory or the large agricultural producer. In these people’s eyes, removing the peril to our health is too expensive. It’s expensive only in the short run, because it obviously costs less and is better for people to avoid developing emphysema or cancer. But those who control factories, mines and hospitals have very narrow, short-range goals—increasing profits. From this point of view, it would cost too much to install an adequate filtration system in a cotton factory. Such a system would decrease the amount of deadly cotton dust breathed in by workers and would decrease the rate of lung disease and cancer in these workers ten to twrenty years from now. But the final decision about the system is made by management, although they do not suffer the consequences.

Anything that interferes with profit and control over how things are produced and marketed is seen as threatening and dangerous by the owners. This is the basis for the conflict between workers and management—they have opposing goals. Workers want safer working conditions, better wages, job security and more say about what goes on at the workplace. Owners are committed to keeping wages as low as they can get away with, not investing in safer equipment and not listening to workers’ problems. To achieve this, they will pay corporations like Melnick to prevent workers from forming unions, and they will lobby against tight occupational health standards. They have many legal maneuvers on their side because our social/economic system, which is capitalist, favors the owners and leaves workers always on the defensive. All of these tactics are seen as management’s right because they own the industry or hospital, although they are not the ones who make the goods or produce the services or take the risks. But should management have the right, in effect, to “own” someone’s health, their lungs—to use workers for 30 years and then discard them?

Our health care system and its shortcomings reflect these conflicts and antagonisms of capitalism. We are always urged to give the best health care we can, but when it comes down to hospital management giving us the means to do our best we are reminded of the budget, of efficiency. When we try to organize to improve our working conditions and patient care, we are told we are being selfish and hurting the patients. Once again the short range view—ensuring the medical industries’ profits—determines the kind of care people get.

We are so used to thinking that management can do what they want with “their” factory or hospital, and that we shouldn’t have a voice because we “just work there,” that we can’t imagine any other way of doing things. There are alternatives—some socialist societies have developed more rational health care systems designed to provide a service to keep people well through preventive care, and to take care of them when they become sick no matter who they are or how much they can pay. Socialist economies are organized to produce goods and services that people need and to plan what is needed in a spirit of cooperation, rather than competition and individual profit. Workers are regarded as essential to the society and have a stronger voice in the owning and operating of factories and services. Thus, health care in these countries is not trying to squeeze a profit out of illness—instead the short-range goal is to care for people and the long-range goal is to keep people from getting sick.

Although we often think of our medical care as the most advanced in the world, our statistics on job-related injuries and illnesses, and our infant mortality rate are not good. We know the treatment for venereal disease, yet it is epidemic in the US—in China VD has been virtually eliminated by educating people and by having health care available both in rural areas and in cities.4 In Chinese hospitals, when patient rounds take place, everyone who works on the floor attends—housekeepers, doctors, nurses and patients. If someone has a better idea about a treatment, it is instituted.

In studying these alternatives, we have seen that there are better ways to deliver health care. However, it is not possible to change one institution like a hospital without changing an entire society. We have shown that the priorities of a profit-making system determine how health care is delivered. We believe we need to reorganize not only our health care system but also our society as a whole, so that we have a socialist economy, in which the people who do the work of maintaining the society determine the priorities. This is a long and difficult process, but it is one we can begin by fighting in our workplaces for control over our working conditions and decent care for our patients.

CONCLUSION

We started this pamphlet by talking about professionalism, but ended up talking about everything from drug company profits to supervisors to racism to unions. Why?

All nurses are dissatisfied for one reason or another. We all would like to see things improve. But how we go about changing things depends on how we analyze our situation. We have to look at the work we do, and the setting in which we do it. We have to understand who is in control and why they think the way they do. We have to discover what influences the priorities and practice of health care. And then we have to use this information to establish who our friends and enemies are and how we should proceed.

Without an accurate analysis, our attempts at change will go around in circles. This pamphlet starts out with professionalism because it is one of the first things we notice when we look at nursing today. But we move on to so many other subjects because we go through all the steps listed above. We wanted to show that:

—professionalism is not what we have been told it is. It teaches us to deny our own needs, to work individually, and to look down on other workers.

—fighting for changes which benefit ourselves and caring for patients are not conflicting goals. Better working conditions equals better patient care.

—the problems of our health care system are due to the fact that it is centered around profits, and administrators have a stake in keeping it that way.

—nursing administrators and their organization, the ANA, are part of management, and they use professionalism as one way of controlling nurses and keeping us separate.

—our most important allies at this time are other hospital workers.

—we must start trying to overcome the things that keep us apart from other workers. We must bring about the unionization of nurses together with all hospital workers as the first step in achieving change.

WHERE DO WE BEGIN?

Small Groups Are One Way to Start

When nurses get intolerably frustrated, we usually quit. If we could make our demands for change through a hospital-wide union, we would have the support necessary to stick it out and fight for what we want. If quitting is our main means of protest, hospitals everywhere will stay just the way they are now.

But most of us do not have any such organization at this point—so where should we start? The nurses that wrote this paper got together in small group meetings outside our various workplaces. We helped each other through the endless individual hassles of being new nurses, as well as challenging one another to think of more general solutions. For us, the first step was to move beyond the frustration most nurses experience on the job. We discovered in one another our support, and our agreement over what makes our working conditions so bad. We realized how destructive the divisions between workers are.

Each person in the group gave a detailed discussion of her or his hospital, which raised issues important to all of us. Our meetings gave us the opportunity to learn about conditions in different hospitals, and what people had done to change them. We educated one another and we urge others to do the same. The self-education of nurses in how to function in labor organizing is just as important as the study of cardiac function, trauma management, or drug side effects. How can we be proud of our medical expertise and yet remain ignorant of the skills necessary to protect ourselves as workers?

The next step for several of our members was to form or join groups with other people at the hospitals where they worked; some of these groups have included all types of hospital workers.

Obviously, meeting in small groups off the job is not the ultimate solution to our problems. We must eventually move into types of organization which include large numbers of workers and which can deal directly with management.

Moving Toward Hospital-Wide Organizations

We look forward to a time when all nurses are active. Though there are some problems with unions, they do improve our economic situation and job security. We encourage nurses to organize into unions for these reasons. We will then be in a better position from which to work for even more important changes in our country’s health care and economic structures. And in unionizing, we will be gaining the experience we need in order to understand that it is possible for us to work together to bring about change.

We hope this pamphlet has shown that the only solution is an organization of all hospital workers united to confront the common problems we face. Professionalism has fostered the image of the model nurse as someone who functions well alone. We would like to see everybody working together more. If everyone is seeking to secure something better for him or herself, with no thought of other workers, change will be difficult and only a few will gain.

State nurses’ associations have taken on the collective bargaining functions of unions to keep RNs loyal to professionalism, and not out of a real interest in giving nurses a stronger voice in the hospital. The MNA, an organization whose active members are predominantly educators, supervisors, directors of nursing and nursing adminstration of all sorts, has a history of neglect of the problems of staff nurses. We cannot allow standards on hospital floors to be determined by people who do not experience these working conditions on a routine basis, or by an organization which excludes all other workers, even LPNs. The management sector of nursing does not have our best interests in mind.

Unionization of nurses will be a gradual process. The nurses’ associations are there. Those of us who are already represented by the MNA may find it necessary to work with the Association for the present. But organizations so top-heavy with management cannot be reformed. We should understand that the nurses’ associations are not the only choice: we can vote to replace the MNA with a union, whose membership includes the whole hospital workforce.

Membership for nurses in the strongest kind of union will only come when we have abandoned professionalism. We must recognize and respect other hospital workers. It is in our common interest to unite with each other. We must recognize and respect ourselves as workers.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Cannings, Kathleen and William Lazonick. “The Development of the Nursing Labor Force in the United States: A Basic Analysis” International Journal of Health Sciences. VoL 5, No.2, 1975, pp. 185—216.

Cummings, Steve, Elizabeth Harding and Tom Bodenheimer, Billions for Band-Aids, MCHR, San Francisco Bay Area Chapter, P.O. Box 7677, San Francisco, CA 94119. (A basic survey of problems in American health care).

Ehrenreich, Barbara and John, The American Health Empire: Power, Profit & Politics, New York: Vintage, 1970. Ehrenreich, Barbara and Deirdre English, Witches. Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers. Old Westbury, N.Y.: Feminist Press, 1973.

Health-PAC Bulletin. 17 Murray Street, New York, N.Y. 10007. (A monthly bulletin covering a variety of health care issues. Packets of reprints available on such topics as nursing, hospital unions, etc.)

Horn, Joshua S. A way With All Pests, New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969. (An English surgeon’s first-hand account of health care in the People’s Republic of China.)

Law, Sylvia, Blue Cross: What Went Wrong, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974.

Medical Committee for Human Rights, Your Rights as a Hospital Patient, Boston MCHR, P.O. Box 382, Prudential Station, Boston, MA 02199.

Rosenberg, Ken and Gordon Schiff, The Politics of Health Care: A Bibliography, Somerville: New England Free Press, 60 Union Square, Somerville, MA 02143.

Women’s Work Project, Women in Health. Union for Radical Political Economics, cjo Julie Boddy, Rm. 807, 2200 19th St., Washington, D.C. 20009.

>> Back to Vol. 10, No. 4 <<

REFERENCES

- Information from Gerald Shea, Staff Director, Mass. Hospital Workers’ Union, Local880, SEIU.

- The Women’s Work Project, Women in Health, Washington, D.C.: Union for Radical Political Economics, pp. 1-4.

- Brodeur, Paul, “Annals of Chemistry: A Compelling lntuition,” The New Yorker, Nov. 24, 1975, pp. 139, 140, 142, 143. Lehman, Phyllis and Larry Persily, “The Hospital: Hazardous Haven”, Job Safety & Health. VoL 2, No.2. February 1974, p. 9.

- Horn, Joshua S., Away With All Pests, New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969, pp. 81-87.