This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The False Promise: Professionalism in Nursing

by the Boston Nurses Group

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 10, No. 3, May/June 1978, p. 20–34

Part I of a Two-Part Article

The second and concluding part of this article will appear in the July-August issue of Science for the People.

INTRODUCTION

We’re a group of licensed practical nurses (LPNs) and registered nurses (RNs) who have been meeting for over two years to discuss conditions and working relationships in several hospitals in the Boston area. One thing we felt it was important to talk about was the issue of “professionalism”, which has continued to crop up in our training, in nursing journals, and at work. Although most nurses consider themselves professionals, we found that this means a lot of different things to different people. To the majority of nurses professionalism stands for qualities we all respect, such as taking responsibility for our work and caring about our patients. Many nurses think of a professional as someone who finds work rewarding and is honest and hard-working. All of these qualities are obviously important ones.

But in sharing our experiences in hospital nursing, we have found that there are other sides to professionalism. For example, many professionals start to feel that they are the only ones who possess the good qualities mentioned above. We tend to forget that the other people we work with are just as likely to be honest and hard-working or to care about the patients and take responsibility for their work. Professionalism teaches us to see ourselves as unique and better than other health care workers. And the more we talked about professionalism, the more we saw that it was used by administrators to make us work in certain ways which are not beneficial to us or to our patients. In other words, professionalism can be used to exploit nurses.

We have come to the conclusion that professionalism in nursing is being used as both a carrot and a stick. As we try to become more “professional” our eyes are glued on the “carrot” of increased respect, rewards, and supposed improvement—and we do not see that behind our backs, professionalism is providing a “stick” that is used to control and manipulate us. We would like to talk about what’s going on in nursing and health care these days, because we believe that professionalism not only does not serve our interests and those of our patients, but more often leaves us feeling unsatisfied, powerless, and isolated from other health care workers.

PROFESSIONALISM: WHAT WE ARE TAUGHT

Our nursing textbooks talked about what professionalism was in very vague terms, removed from the real work-life of the nurse on the floor. We learned that a professional is someone who has had specialized training which includes a code of ethics, through which members learn standards of behavior to which they are expected to conform. One thing that gives a professional group power is the fact that it is a legally recognized entity: a profession is self-defined, self-regulated. We are told that RNs control their work and set limits on who can perform any given task. (For example, nursing practice is supposedly governed by the Board of Nursing in any given state.) Finally, while being a professional demands a set standard of performance, the profession is supposed to protect its members and their interests.

Nursing is supposed to be a unique profession in that it’s a balance between physical work and using our heads. While giving a bedbath we’re doing more than just washing. We can evaluate range of motion and we might notice a rash or the beginning of a bedsore. Frequently we’re in the position of making judgments about patients’ meds—like holding someone’s Valium because they’re too drowsy, or their Dig1, for a slow pulse. Much of the day-to-day information about the patient is channeled through the nurse, who makes decisions about calling the doctor.

The idea that we are more than manual laborers is stressed from an early point in our education. Although we do physical work like other hospital workers, we are taught that we are more like doctors. We have specialized education, we write in patient charts, which are part of a legal record, and we make decisions that directly affect patient care. Doctors will seek us out to ask how their patient is doing. In Social Service rounds we can talk about financial worries or home problems that no one else has picked up.

Nurses are taught to identify the patient’s psychological as well as physical needs—such as helping a patient cope with an ileostomy2 or some other radical body change. We are told that these are skills that other people don’t have or are unable to develop without going to nursing school. Another big part of RN training is skill in “leadership” and management of other nursing personnel—taking charge, organizing a team assignment, checking up on other people’s work. As professionals, we are told that we are the best qualified to decide how work is done on our unit.

We are promised many rewards for being professionals—good salaries and fringe benefits, job mobility and job security. With a BS or MS we are practically guaranteed the chance to move up the ladder—become a head nurse, supervisor, clinical leader or nurse practitioner. Even if we don’t go on to school, workshops and conferences keep us increasing our knowledge. We are supposed to have some independence regarding the pace of work and the priorities we choose to set.

A lot of us went into nursing for another, different reason, that has to do with helping people. A big role we play is that of guardian of the patients’ dignity and overall well-being. We want to give them the best possible care and protect them from disappointments. Our needs to feel useful are supposed to be satisfied by the unique and special nurse-patient relationship.

All of these are rewards that we expect from being a nurse. What is the actual situation?

PROFESSIONALISM: ON THE JOB

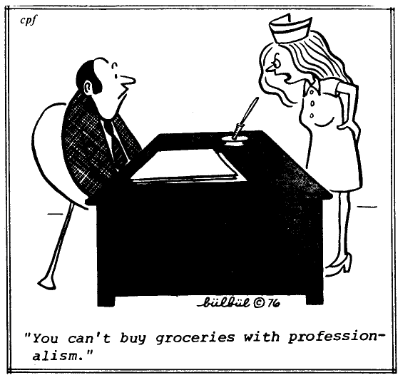

We do receive some concrete benefits for being seen as professionals. RNs get paid relatively well—almost twice as much as nurses’ aides. We have more job mobility than most workers. We can change jobs, have a family, move away, or quit to go travelling, and still be pretty sure of finding work.

There is also mobility within an institution—you can transfer to a less tiring or more challenging unit, although sometimes the promise of a transfer is used to hold you on an unpleasant floor for months. However, job mobility within nursing is decreasing. With cutbacks in the economy, nurses who leave their jobs often are not replaced. It is harder for new grads to find jobs, and layoffs, especially in public hospitals, are becoming more common. Another factor is that within the past few years there has been a flood of people into nursing. So the old myth that “you can always get a job if you’re a nurse” is becoming less true as more people are competing for the jobs. There is also upward mobility within nursing: head nurse, supervisor, and the new position of clinical specialist. Yet in most hospitals these positions are only open to nurses with BS and Master’s degrees. Many hospital-based programs are being phased out and a BS degree is becoming more and more the only acceptable nursing credential. So the drive to “upgrade” nursing serves in the end to make the jobs of nurses without BS degrees less secure. LPNs and diploma grads are being phased out at hospitals where they have worked for many years, and are being replaced by baccalaureate RNs who have little or no clinical experience. At the Cambridge Hospital, for example, the number of LPNs has been reduced from 40 to under 10 in the past few years, and RNs without bachelor’s degrees are rarely hired.

But what about the more intangible aspects of being a “professional nurse”, for example the nurse-patient relationship. We were taught that we would be the guardian of the patient, enjoying a relationship that no one else who worked in the hospital would have. We would determine the patient’s real needs, protect him/her from the errors of doctors and hospital bureaucracy, help her/him figure out and solve all problems. In nursing school we were able to focus our energy on one or two patients at a time, read their charts before or after clinical practice, spend hours at home doing lengthy care plans. We often were able to develop relationships that were significant to the patients and fulfilling to ourselves.

But even caring for only one or two patients we “guardians” run into problems sooner or later. One nurse in our group took care of a 55-year-old man who had had a stroke. “The guy was totally freaked out. His whole life was abruptly changed. I called a psych consult because he needed to be able to talk to someone about what was happening to him. The shrink came and only prescribed mood elevators. We wanted to send him home with a homemaker and physical therapy, but he had no medical insurance. We couldn’t get state money for home care, so even though a nursing home was more expensive, that’s where he ended up, and there was nothing I could do about it.” This story is just one example of the many barriers to decent patient care. Even with all the time in the world, we as individual nurses are unable to overcome the obstacles presented by the way health care in the United States is organized.

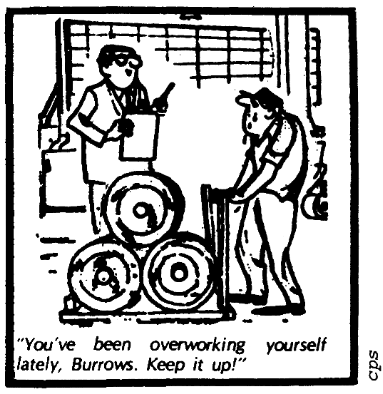

And once we get out of school most of us don’t have all the time in the world. A day on the floor is like a beat-the-clock contest: 7:30 vital signs, 8:00 meds, 8:30 feeding patients, 9:00 baths, 10:00 meds, 11:00 premeals,3 11:30 vital signs, 12:00 feeds, 1:00 putting patients to bed, 2:00 meds, 2:30 charting, 3:00 report. We’re as confined to the clock as if we worked on an assembly line instead of in a hospital. There are differences: factory work is more boring, more alienating, often more tiring. The boss is there to tell you that you can’t leave the line to go to the bathroom. We have no foreman controlling our every move. But through nursing school and the professional ideals taught there, the boss has moved inside us. We still don’t get to the bathroom until lunch (if we get lunch).

If we are lucky we are done at 3:30 but probably not, so many nurses will still be running around until 4:30 or so, usually without overtime pay. We don’t ask for overtime because we know we won’t get it unless the floor is in an unusual crisis. So why do we stay? We are made to feel guilty. We feel that it’s our own fault if we don’t get our work done even though we know that the real problem is understaffing. A little voice inside may be saying, “Well, if only you were more organized”. Or maybe we feel that it’s expected, that we can’t leave if everyone else stays, and that we don’t want to leave all that work for the next shift.

Why do nurses put up with these lousy working conditions and believe the myth that we have control over our work? Because we have an image of ourselves as professionals, we blame ourselves if we don’t finish our work, don’t develop significant relationships with patients, and don’t feel that we have control over our work day. The ideology that surrounds the nursing profession forces us to blame ourselves for situations over which we really have no control, and reinforces our passivity. This ideology keeps us from identifying the real sources of our problems. When we are fed up because of poor staffing, broken equipment, and lousy staff relations, professionalism keeps us from getting together to change our working conditions. Instead, it turns us back on ourselves to examine our own faults.

One of the hardest things about being a new graduate is getting used to the fact that working as a nurse is very different from the “profession” we learned in school. Even if we have time to try to be the patient’s guardian we run up against doctors, bureaucracy and the inadequacy of health care in this country. As professionals we are supposed to have control over our working conditions. But we have very little control over some very important aspects of our work—such as staffing (who and how many), hours, quality of care, discharge planning, treatment of patients, who becomes a patient, nursing policies—the list is endless.

Many of us start work with high expectations of our “expanded” role. Traditional nursing education taught us to be the handmaiden of the physician. But the women’s movement has left its impact on nursing. We have a greater sense of our own worth, as women and as men in a “woman’s” job, and have started to demand respect from others on the job. Many baccalaureate RNs are taught to see themselves as the physician’s colleague. We all expect to make decisions about patient care. But our attempts to exercise our judgment are often frustrated, and we become outraged when we see patients suffer because of it. We take out our hard feelings on other nurses, aides, housekeepers, even the patients. It doesn’t help, but what can we do?

The women and men in our group got together because we wanted to do something more constructive with the anger we bring home from work. Many of us had been in consciousness-raising groups, in which we had discovered that our “personal” problems were shared by others. We had learned to look beyond our individual lives for the causes of these problems, and decided to use this skill to explore our “personal” problems as nurses. We started to ask ourselves why there was such a difference between the nursing we were taught in school and nursing on the job. Why did we feel so bad at the end of a workday? Why was it so difficult to give good patient care?

As nurses, we have the goals of better patient care and better working conditions. We decided to look beyond nursing, at the rest of the hospital. Who else shared our problems, and our goals? And why are these goals so difficult to achieve?

HOSPITALS: IS HEALTH CARE THEIR GOAL?

We asked ourselves if good health care is really the goal of the hospital industry. Most of us who work in hospitals can think of many examples which tell us that other motives come first: unnecessary procedures and operations to provide learning experiences; little or no preventive health care; understaffing or poor equipment when money is being spent for some specialized medical machine already available at another hospital. We frequently find that hospitals are more concerned with profits, teaching and research than with health care. Banking, drugs, supplies, construction, real estate speculation—all are so closely tied into the health care industry that some have called it the “medical-industrial complex”.4

Most private hospitals are officially “non-profit” institutions. Usually people think this means that the hospital only takes in enough money to pay for the expenses of patient care and staff wages. In reality, “nonprofit” means only that the hospital’s excess income is not distributed to shareholders. But the profits are there—they are used to finance expansion, new equipment, fancy offices and high salaries for administrators. Two advantages of “non-profit” status are Federal assistance for expansion and exemption from taxes.5

Recipients of hospitals’ “non-profits” include drug and hospital supply firms. In the 1960s, the drug industry was consistently one of the three most profitable industries in the United States.6 Hospital supply companies have an almost unlimited future in disposable goods, as hospitals resterilize only the most expensive equipment. Aside from traditional hospital firms, drug companies (like Smith, Kline & French), paper corporations (Kimberly-Clarke) and conglomerates like 3M (makers of Scotch tape) are diversifying into hospital equipment.7

Hospital expansion is so profitable for construction companies, lawyers, architects and banks that many areas of the country have too many hospital beds: San Francisco has 1130 extra beds; Honolulu 1000; Oklahoma City, 1946 extra beds – with more expansion planned.8 Not only are expansion plans made with little regard to actual need, but the impact on the surrounding community is often ignored. In Boston, residents of the Mission Hill neighborhood have been fighting expansion of Harvard Medical School’s teaching hospitals for 15 years. Harvard is the major landlord in the area, and has been trying to tear down the housing it owns to build the Affiliated Hospital Complex (including Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Robert Breck Brigham Hospital and Boston Hospital for Women). Rather than providing health services for the community, the original plans would have destroyed one of the few remaining inner-city neighborhoods in Boston. Only constant organized resistance by the Mission Hill residents delays the takeover of their homes by Harvard Medical School.

We hear all the time that there’s not enough money for wages, staffing, or supplies. So it may be a surprise to learn that all this profiteering and expansion is going on. Why is the decision made to spend money building unnecessary hospital beds instead of hiring more nursing staff or buying more wheelchairs? Who decides where the money goes?

HOSPITAL ADMINISTRATORS: DO THEY SHARE OUR GOALS?

Most private hospitals are run by Boards of Trustees or Directors, who have the final say in policy decisions. Trustees do long-term planning and choose which banks, construction companies, etc. the hospital will use. Actual day-to-day control of the hospital’s policy is more likely to be in the hands of the hospital Director.

The people who sit on hospital Boards of Trustees are frequently the same people who sit on the Boards of companies in hospital-related industries. At Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Trustee Ernest F. Stockwell is also president of the Harvard Trust Company, which profited from holding the mortgage on the new Mt. Auburn building. Mr. Stockwell is also a trustee of University Hospital, and is a director of a gas company and an engineering corporation. In fact, of the 24 trustees listed for Mt. Auburn in 1972, no less than 14 were directors or Board members of banks or banking-related organizations; three were connected with the realty business; three with power-producing firms; and three were trustees in other hospitals besides Mt. Auburn.9

Across the river in Boston, the hospital-corporate connections are similar. Mitchell Rabkin, General Director of Beth Israel Hospital, is a member of the Board of Trustees of MASCO (Medical Area Service Corporation). MASCO proposes to provide hospitals in the Longwood area, such as Beth Israel, with everything from linen to electricity.10

With such close connections, it’s not surprising that hospital Boards make decisions that reflect their own profitmaking interests more than the interests of the patients or hospital employees. But what about the hospital Director? Could he/she share our goals?

The Director is usually a person with special training in hospital administration, whose job is to run the business efficiently and save money. It is important to control the workforce, which includes making sure that employees don’t step out of line and make costly demands on the administration. At a larger or more prestigious institution, like Beth Israel, the Director may have the same business connections as the Trustees. At all hospitals the Director is the public voice of the Board of Trustees and shares their interests, not ours.

What about doctors? Don’t they make a lot of decisions? Can they be our allies in seeking better health care? There are some individual doctors who are genuinely concerned about health care. But as a group, doctors are more concerned with their incomes or with research, or both. Their interests in hospitals are primarily as free office or laboratory space. Interns and residents are in a slightly different position – they are overworked and are more directly affected by understaffing than the private doctors, because it means even more work for them. House officers’ associations have occasionally made demands about hiring more lab and nursing workers. But their situation is only temporary—they are on their way up and out, so we cannot depend on them for long-term support in our efforts to gain better working conditions.

NURSING ADMINISTRATORS HAVE DIFFERENT PRIORITIES FROM THE STAFF NURSE

As staff nurses, we are not constantly aware of the top administrators and trustees. We never see them, though they make decisions that affect our life at work every day. Nursing administrators are a little different. Though we may seldom see the Director of Nursing, supervisors are usually around, at least for scheduling or to announce new policies. If we have a grievance, we go through “proper channels”—that is, the supervisor’s office. It seems as if they should be sympathetic to our problems. After all, they’ve been trained as nurses—they know the demands of our work. Since they visit the floors, they should have some idea of how many patients we have and what care they need. So it is doubly frustrating when we get no response from a nursing supervisor—or worse, get treated like a nuisance for mentioning problems in the first place. Why don’t they know what the floors are like? Why can’t they imagine what it’s like to have too much work and not enough help—and do something about it?

The point is that even if a nursing administrator has given direct patient care at some time in her career, the majority of them never touch a patient. Their priorities are completely different from those of a floor nurse. The nursing director is supposed to provide nurses for staff duty, but she can hire no more than the budget allows. Staying within the budget is one of the main concerns. She is also expected to manage her personnel by means of the supervisors. This is how hospital policies are put into effect, and how discipline is maintained, whether the issue be wearing caps or signing into work. The director is also expected to keep her department up to par for JCAH (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals) and public health inspections, stressing things like nursing audits, progress notes and care plans, even if there aren’t enough people to do the job properly.

Some supervisors try to listen, and argue for funds to hire more nurses or get more supplies. They may urge staff nurses to document poor patient care due to inadequate staffing. This kind of supervisor usually doesn’t last too long since administrators may feel she “can’t handle” her job, which is to maintain the status quo. Some supervisors don’t care at all about the realities of staff nurses’ problems or make even more demands. When the floor is the busiest we are asked why a bed isn’t made or why our shoes aren’t polished.

Professional Associations

Nurses who try to take their grievances through proper channels—that is, nursing supervisors or directors, are frustrated and realize they will get nowhere this way. Some RNs consider the alternative of going to their professional organization (usually a state branch of the American Nurses’ Association [ANA], like the Massachusetts Nurses’ Association [MNA]), either for individual advice or group representation. Nurses are told these groups will give the best help because “nurses need other nurses to understand their problems”. But as we can see from looking at nursing supervisors and directors, the fact that someone is a nurse doesn’t necessarily mean they care or can do anything about the problems facing a staff nurse.

Another drawback is that the ANA has a relatively large number of administrative nurses in its top positions. The disadvantage of this can be seen in the example of an operating room (OR) nurse who was worried about understaffing in her area, and asked her state association for help. Unfortunately, one of the association’s officials knew the OR nurse’s supervisor—and told her friend to “watch out for that troublemaker” on her staff. So, having managerial level RNs represent staff nurses does not guarantee impartial help or advice.

In spite of this potential conflict of interest, the ANA considers itself the voice of nursing. It has publicized the ideas of the nursing leadership since it was founded in the 1890’s, and takes credit for the improved status of nursing since that time. How did the organization become so prominent, and how much has it worked for the rank and file nurse?

The ANA and the Staff Nurse

Until the 1920’s the average nurse did private duty work, often in the patient’s home.11 Since nurses worked in this way, isolated from one another, it was difficult for them to band together to work on common problems—such as irregular work, long hours without relief, or difficulty getting paid for their work.12 Thus the ANA, run by financially secure, upper class nurses, was virtually unchallenged in its role as the major nursing organization.

The main goal of the organization has been to make nursing more respectable and prestigious, not always to the benefit of the average nurse. The ANA’s work on the issues of licensure in the 1910s and of control of nursing education in the 1920’s had some good effects. Licensure standardized qualifications somewhat and made some nurses’ jobs more secure by limiting competition. However, it also disqualified some very competent nurses who had been trained outside the hospital school system.13 The reform of nursing education begun in the ’20s eliminated some of the schools that used students’ unpaid labor without providing sufficient instruction.14

But graduate nurses continued to face difficult working situations and economic insecurity. The Report of the Grading Committee on Nursing Education (1928) mentioned their problems over and over again, but its main accomplishment was to recommend closing some nursing schools and to join the trend begun by the Goldmark Report in 1922 for more education for nurses.15 The effect was to reduce the numbers of new graduates competing in the job market and also to exclude many women who could have been skillful nurses but who did not have something the Committee called “good breeding”. The feeling seemed to be that if more women from the upper class became nurses, a lot of the on-the-job problems would disappear.16

Unemployment among nurses increased with the Depression and it became evident very few people could still employ private nurses. More people entered hospitals for medical care, and the hospitals finally decided (with some misgivings) to staff their floors with graduate nurses in place of unpaid students, as the nursing schools were getting too expensive to run.17 Many nurses were reluctant to do hospital staff work, realizing they would lose the chance to give the one-to-one care possible in private duty. Though they gained a regular paycheck, they now had more work than they could do; faced by a wardful of patients, they were forced to lower the quality of their care.18 They still worked long hours, but had lost their freelance independence—falling under hospital discipline for style of hair and uniform, relationships with doctors, use of supplies. The hospitals compensated by giving RN’s a position of minor influence in the hierarchy. Eventually RNs identified with the hospital administration. They “gained” petty control over other workers, but lost control over patient care.19

Over the next 20 years, the ANA continued to emphasize collegiate training for RNs. Once again, many people have been excluded from opportunities in nursing, since this type of education requires a lot of money and time. A prime example is that of LPNs, whose education and experience is deemed worthless in most states (by Boards of Nursing overwhelmingly controlled by RNs and MDs). It would be possible to structure LPN education so it would count towards future RN training, but RN leadership has blocked this possibility.20 RNs with diplomas are hurt by the current trend, too. One diploma RN was enraged by her interview for a BS program: “They treated me as if I’d barely graduated from high school.”

While it has been mandating more education for RNs, the ANA has mostly ignored the actual working conditions of the majority of nurses. The organization puts a lot of time and money into legal support of nurse practitioners, but its collective bargaining function is a low priority even though it involves relatively greater numbers of staff nurses. The MNA, for example, is known as a weak bargaining agent, delegating a small proportion of its resources to negotiations and grievance procedures.21 The mistaken concept of the 1920’s seems to persist—if only nurses were “better people” (from wealthier families? with only BS and MSN degrees? working as practitioners? more like MDs?), then these problems of understaffing, lack of supplies, unpaid overtime, etc. wouldn’t exist.

There is also the question of staff nurses having any power in an organization dominated by top-level supervisors and educators. From time to time, staff nurses at Boston City have documented instances of unsafe patient care (mostly due to understaffing) for their MNA unit to present as a grievance. Much of the nursing shortage was due to cuts implemented by Ann Hargreaves, Nursing Director of the Department of Health and Hospitals. At the same time, Ms. Hargreaves was state treasurer of the MNA, signing the paycheck of the staff nurses’ bargaining agent, who was in charge of pursuing the grievance. With such conflicts, can staff nurses rely on professional organizations as their advocates on the job?

WHO DOES SHARE OUR GOALS?

Patients

It seems clear that, lacking the same goals, nurses should expect little support from administrators and professional organizations. But nurses are not alone in their desire for better care and better working conditions. It may surprise us, but patients are strong potential allies. We both share one basic goal—good patient care. We lose sight of this important fact as the pressures we work under alienate us from the people we care for.

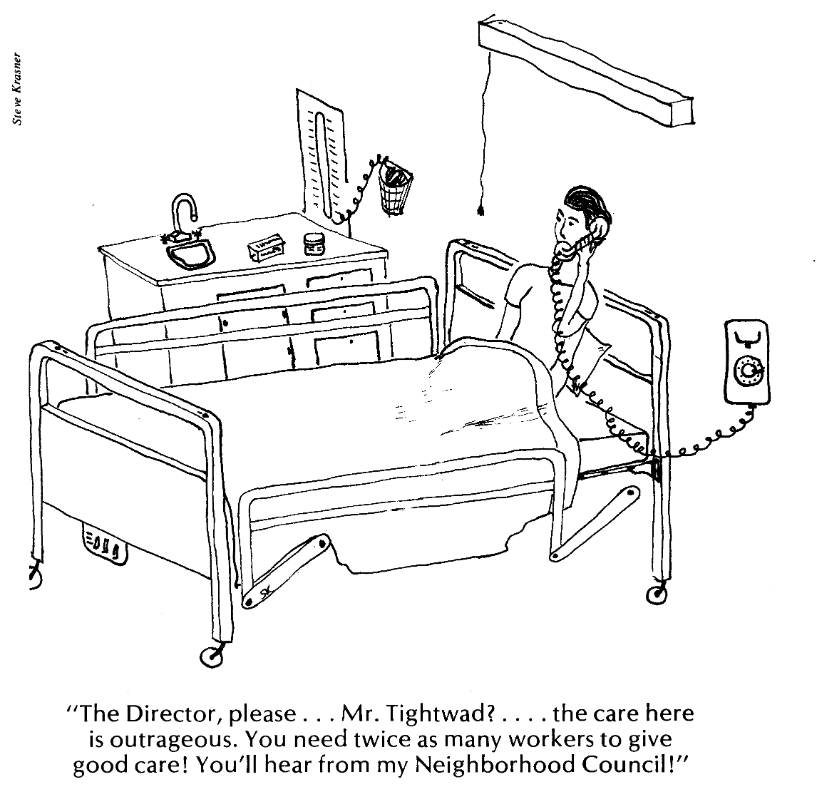

Our working conditions force us to neglect all but the most pressing medical needs of our patients. They soon learn that we give more attention to the sickest patients and to the ones who complain the most. Patients end up thinking they have to fight for the care they need and deserve. As a result, they sometimes treat us as if we were enemies, as the immediate representatives of a system that isn’t responsive to them.

When patients challenge us, it reminds us that the whole system of health care is not really set up to help people, and that they’re suffering from it along with us. We know only too well, for example, that patients are experimented on in blatant and subtle ways, and that we are expected to cover up the resulting mistakes and inconveniences. We sympathize with them. Yet when we are overworked, we see their demands as just one more obstacle to overcome before we go home.

This antagonism is neither our fault nor the patients’—it’s built into the hospital structure. Earlier in this paper we talked about the ways nurses were incorporated into hospitals in the 1930s: hospital administrators deliberately broke up the one-to-one nurse-patient relationship because it was too expensive. Today, adequate staffing is still too “expensive.” Our instincts and training lead us to expect good patient care conditions, but we usually run into trouble on the job if we insist on these conditions.

We think that the solution is not to go back to the days of private duty nursing, but to find ways to get together with our patients to demand better conditions for them and ourselves. Together we could face the real obstacle, the hospital administration.

Other Hospital Workers

The work of the hospital is to provide health care. This work involves a lot of tasks besides giving bed baths and medicines, changing dressings, and doing patient teaching. Sick people need to be in a clean, safe environment—which means constant cleaning and constant maintenance of equipment. They need to eat special foods, and the food has to be delivered to their bedside. Patients need laboratory tests, X-rays, and respiratory treatments. Drugs and supplies used in their care have to be ordered, stored and delivered to each floor. Records of patient care have to be made, updated and filed. Most of this work is unglamorous and doesn’t pay well. But all of this work is absolutely essential. Our work as nurses would be impossible to perform without dietary, maintenance, housekeeping, clerical and technical workers.

The reason we discuss other hospital jobs in such detail is that we have sometimes found in ourselves and other nurses a lack of respect for other hospital workers. One reason for this is that our society values mental labor more than manual labor—so that doctors are more respected than nurses, who are more respected than aides or housekeepers.

We have also been encouraged to think that we are the only ones who care about the patients. In nursing school we are taught about meeting all the needs of the patient and forming “therapeutic relationships.” But this schooling can make us forget that caring doesn’t come from ideas in a book, that you don’t have to be “qualified” to care about patients. Caring comes from the person, not from nursing school or professionalism. Many nurses are dedicated, compassionate individuals, and some aren’t. It works the same way for other people who are involved in hospital work. If nurses care about patients it’s not because of professionalism or training. (Look at doctors with all that training. Do they necessarily care about the patients more than we do?)

Why all this talk about respect? We think that nurses’ ignorance about other hospital workers blinds us to the fact that they are the people in health care who have the most in common with us. There are obvious differences in training and pay, but the differences are small when our salaries are compared to those of doctors and administrators. And we face the same problems on the job. Whether one is a housekeeper or a nurse, we have little or no input into hospital policy, wages, employee benefits, staffing, the way health care is delivered, etc. In other words, none of us has much control over our job. If we continue to blame our problems on our fellow workers and refuse to see them as allies, we are only hurting ourselves in the end.

HOW DO WE ACHIEVE OUR GOALS?

To many of us it seems unusual or inappropriate to think of getting together with housekeepers or maintenance workers or of taking joint action with our patients. This is partly because we’ve always been told that we achieve change by going through proper channels—which means working it out with your supervisor, or trusting some administration committee to work on the problems. The effect is to make us feel that we aren’t smart enough or don’t know enough about the situation to come up with any good solutions with our coworkers. And of course, administration would like us to think that employees below us are even less capable of solving problems.

We’ve already stated why we think the proper channels won’t get us very far. But what else can we do?

We’d like to give a few examples of situations in which patients and hospital workers joined forces to fight for a health care issue. We’d also like to talk about organizations that other hospital workers have used to defend themselves at work.

Worker-Patient-Community Efforts

In 1975, Massachusetts tried to close the Shattuck Hospital, a large rehab and chronic care facility in Jamaica Plain. The state claimed the hospital was too expensive to run and that it was only half full. Workers employed at the Shattuck felt insecure about their futures. They fought to keep the hospital open and gained a lot of strength from the efforts of former patients and families of patients. The group pressured state legislators, started a sticker campaign and pushed the issue into the media, with successful results: the hospital stayed open.

In the same year, Boston State Hospital was operating with at least 90 staff positions unfilled, and with supplies such as toilet paper and soap unavailable. There was no clothing for patients, and they had to share dinners, as the kitchen could not send enough food to each floor. Nurses at the hospital organized a demonstration at the State House to demand more funds. This demonstration was attended by 150 staff members and patients. The next day, staff was informed that each patient would receive a new outfit of clothing. But when it was clear that basic conditions were still not improving, RNs and LPNs staged a one-day sickout. That day they were notified that the 90 critically needed positions would be filled.

Unions

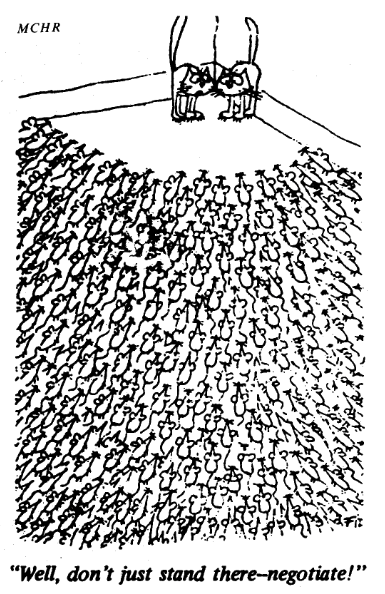

We have two examples of successful coalitions involving hospital workers and patients or community members. These coalitions were formed around a single issue and stayed together for a short period of time, so were limited in what they could do. We need to organize ourselves so that we can work on more long-range goals and deal with many issues. As a first step we need to defend our rights on the job, so that we will be protected in working for the changes we need to make. A good place to start is with unionization, specifically, unionization which includes all workers in a hospital in the same union. The more our group talked about the need for change, the more we realized that hospital unions are an important first step in achieving better conditions.

But nurses often have a lot of fears concerning what unions may do to health care. Some feel that a union is an outside organization, that will tell workers what they have to do. Others feel that unions are “unprofessional,” harmful to patients because they promote strikes, and that they will encourage laziness. There are many people who think unions are always corrupt, and that in any event they tend to take in more in dues than they deliver in the contract.22

Not all of the fears listed above come out of thin air. But many of them are misconceptions. When workers suffer from low pay, bad working conditions (such as long hours, dangerous conditions, etc.), lack of recognition for their work, or poor benefits, they need to improve their position by joining together so that their employer has to listen to what they have to say. Workers organizing unions realize that when they act only as individuals they can’t change the quality of their jobs.

What is a union?

Collective bargaining is the process of negotiation between workers and management to produce a contract that both sides will agree to. A union is an organization of employees which carries out collective bargaining with the employer in order to improve the jobs of its members.

Patient Care

Some nurses who are reluctant to unionize feel that improving their own conditions can only take place at the expense of the patients. But just the opposite is true. When people don’t like their jobs, they don’t do good work. In hospitals, it is important that people have good working conditions since their jobs affect not only them but also the patients, in a very direct way. Nurses, just like all other hospital workers, have the right to demand improvements for themselves. And patients will benefit from good working conditions for all hospital workers.

Hospital Unionization

Unions have a long history in the United States, going back into the last century. It was during the 1930s, however, that large numbers of workers started joining unions. This was the beginning of the unionization of the major American industries. We take this for granted today, but at that time there were many bitter struggles by American workers to establish their unions.

In Boston and in many other cities, most hospital workers are still not unionized. Why has the health care industry lagged so far behind other industries in this regard? For one thing, workers in voluntary23 hospitals were not protected by federal labor laws until 1974.24 (In some states, local laws were passed before 1974 which gave unions some protection from unfair practices by employers in that state.) Also, in earlier years, hospitals were still viewed as charitable institutions. Nowadays people are more likely to understand that hospitals (especially voluntary and proprietary25 hospitals) are powerful institutions that control large amounts of money. So hospital unionization has only really gotten underway in the last 10 to 15 years.

In New York City, where hospitals are heavily unionized, the minimum wage is now $181 for 40 hours.26 But in 1959, before organizing efforts began, the minimum wage in private hospitals was $30 per week for a 48-hour week.27 Many hospital workers who worked full-time – or more – where forced to apply for welfare to support a family.

“Unprofessionalism”

During the 1960s, when hospital organizing and occasional strikes were taking place in some cities, many professionals and professional associations objected to these tactics. Nurses denounced the strikes and broke picket lines. The failure to respect a strike is not surprising in view of the fact that the ANA promoted a “no-strike” policy from 1950 until as late as 1966, when it was rescinded.28

The professional associations that once said unions were “unprofessional” have now begun to recognize that they must use the same methods if they want to make progress. What these groups haven’t wanted to recognize is that their members’ wages have been pushed up largely by the organizing efforts of workers “below” them. As union contracts have improved the wages and working conditions of service, maintenance, and technical workers, administrators have raised salaries of “professional” employees to keep pace.

Inflation, the flooding of the job market and the deteriorating conditions in hospitals have affected us all. Many of us have faced understaffing, floating, inadequate supplies, and cutbacks in benefits. These are the conditions which made nurses in San Francisco, Baltimore, Seattle, Honolulu and Chicago go on strike. These nurses saw that the old appeal to professional sacrifice for the patients’ sake is baloney. Nurses have now begun to organize.

If being “unprofessional” means uniting with the majority of health care workers to bring about improvements, instead of trying to make it on our own by becoming a more elite group, then we could use a lot more “unprofessionalism”!

Union Democracy

Some people fear that a union is an outside organization that will tell them what they have to do. But the activities of a union depend on the activities of its members. When unions are young and struggling, their members are actively involved. As they get bigger and stronger, their leaders tend to lose touch with their membership. There are many stories in the press about corrupt union leaders and the lack of democracy in unions. In addition, union leaders are reluctant to challenge the status quo, and often end up justifying management’s positions to their membership. These are the possible results of a situation where the union leadership no longer identifies with the workers but spends most of its time talking with managers. (In a professional association such as the MNA, the leaders actually are the managers, which is far worse!)

Union members are often encouraged to be passive, and to trust in the leadership to “get things” for them. But unions are only democratic when their membership stays actively involved, and insists that the leaders serve their needs.

| BREAD AND BUTTER ISSUES—UNIONS DO MAKE A DIFFERENCE

Boston San Francisco (largely non-union) (largely union) Non-government hospitals: General duty nurse $184/wk $211/wk LPN 148 165 Aide (female) 108.50 145 Non-federal government hospitals: General duty nurse $188 $218 LPN 153 164 Aide (female) 123.50 150 Source: Cannings and Lazonick, “The Development of the Nursing Labor Force in the United States: A Basic Analysis”, International Journal of Health Services, vol. 5, no. 2, 1975, p. 190 (table 3). |

Protection on the Job

Hospital administrators tell us “a union will take all control away from you.” But any hospital worker who thinks she already has control over her job is not looking at reality. Even RNs, as we talked about earlier, are not really given any control—just the right to tell other workers what to do. While hospital unions are not going to give us complete control over our work, they are crucial in gaining basic improvements. For example, unionized workers have more protection from unfair practices by supervisors. They have a grievance procedure, which can provide a more equitable way of dealing with problems. Because they have some protection against arbitrary firing, they are less afraid to speak up, to suggest changes, and to get in touch with each other about various issues.

Of course, there are also more concrete benefits to be gained from a union, such as improved health insurance coverage, pension and compensation plans. And most workers feel that the wage increases and other improvements make it very worthwhile to pay dues, which usually run about 1-2% of wages. Dues paid to a union go to help pay salaries for neogtiators, organizers, and lawyers, and to pay for the costs of everything from leaflets to contracts.

Hospital Costs

Another argument commonly used against unions is that they are supposedly responsible for driving up hospital costs. There’s more here than meets the eye, however. For example, although total salary expenses for some unionized hospitals have more than doubled, part of this is due to the fact that hospitals are hiring more workers per patient than previously. Secondly, it is necessary to look at which employees’ raises take up the greatest part of the increased costs. For instance, in a four-year period in New York City, “while orderlies’ wages went from sixty or seventy dollars a week to $100 a week [ = $5200/yr.] in New York…the average net income of full-time hospital radiologists were jumping from $26,000 to $34,000.”29 Probably most important is the fact that nonlabor costs have risen as rapidly as labor costs. Because Blue Cross and Medicaid accept the hospitals’ estimates on the cost of care, hospitals have been able to buy large amounts of complex equipment and expand their research according to their own priorities. They then include all this in their calculation of costs, so that the cost-per-day of treatment has risen dramatically. Through their insurance premiums, the consumers, instead of the hospitals, actually end up paying for both necessary and unnecessary “improvements.”30 Thus there are many reasons for increased hospital costs, and better wages are only a part. It is time that hospital workers stopped subsidizing hospital costs by sacrificing their living standards through poor wages.

| A UNION CONTRACT VERSUS A PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATION CONTRACT

The chart below contrasts the benefits of two 1975 contracts for nurses at Babcock Artificial Kidney Hospital in Brookline, Mass. One contract was negotiated for LPNs by the National Union of Hospital and Health Care Employees, District 1199 Mass., and the other, for RNs by the Mass. Nurses’ Association. They were negotiated at the same time. Both types of nurses pay dues to their organizations. Union benefits for LPNs Mass. Nurses Assoc. benefits for RNs Pay raises 30% incremental raises from March 1975 through Jan. 1976; $47 increase 9% incremental raise for same period; $20 increase Medical benefits 100% of all medical and hospital costs for all LPNs and families 80o/o family medical costs and all hospitalization; for full-time RNs only Dental benefits 80% of family costs None Prescription drug benefits All family prescriptions paid None Maternity leave 13 weeks leave at 2/3 pay (untaxed) Unpaid leave Staffing Formal bimonthly meetings with management to deal with staffing RNs have no say Management rights Management may not do anything arbitrary, capricious, or in bad faith No controls on management authority Other benefits such a holidays, vacations, liability insurance are identical for RNs and LPNs. Finally, whereas members of the union have the legal right to strike (if they so choose) for a new contract, the MNA has agreed in writing never to strike under any condition (even if their members choose to do so). |

Laziness

Do unions encourage workers to be lazy? There is no guarantee that anyone will work more or less hard in a unionized hospital. But it is possible to see where laziness comes from. When people don’t see their jobs as leading anywhere, when they have supervisors over them who don’t work or who are disrespectful, when they get low pay for long hours: this produces the feelings of “alienation” that make us feel like “it’s not worth it” to try hard to do a good job. Hopefully, by increasing the benefits available from a job, and the amount of input a worker can contribute to the workplace, we will all feel more positive about the quality of our jobs.

| FROM THE HORSE’S MOUTH

Notice how we always hear that higher hospital costs are due to wage increases? But, according to the Council on Wage and Price Stability, half the increase in health care costs comes from the increase in new services and purchases. The other half is taken up by increases in both wages and materials. This means that considerably less than 50% of the rise in hospital bills can actually be attributed to wage increases. (Staff Report, Council on Wage and Price Stability, Problems of Rising Health Care Costs, Executive Office of the President, April1976, p. 12, table 6.) |

Strikes

But what about strikes? If nurses join unions, won’t we be forced into strikes, and isn’t that bad for patient care? These are important questions to answer, because this is the tactic that nurses object to most frequently. Strikes are given a lot of attention in the press, and administrators always try to use them to scare workers away from unions.

For one thing, unions do not automatically lead to strikes. Once in a union, workers have more ways available to solve conflicts than they had previously. Workers cannot be forced to strike by their union. A strike takes place only when the workers in the hospital vote for it.

People do not enjoy going on strike. When issues are being negotiated, a strike is usually the last resort, after all other methods have failed. Management does not give in to our demands because they want to. They give in because they are forced to. They control the conditions of our work; the only control we have is whether or not we work. A strike is a statement by workers that unless management recognizes their right to what they’re asking for, they will refuse to work. Nurses make this statement all the time, whenever we quit to look for a “better job.” But acting as individuals, we have no power.

It is certainly true that strikes cause hardships for patients. What can be done about this? There is a federal requirement that the union must warn the hospital in advance that it is planning to strike, so plans are made by the hospital before the strike to provide for essential patient care. (This law was made primarily to benefit the hospital’s economic interests, not to help the patients.) However, strikers have often taken the responsibility to ensure patient safety during the dispute. In Connecticut, for example, striking nurses sent a team into the hospital each morning to check on critical patients and to see if any extra measures needed to be taken.

Hospitals are often willing to run their floors with poor staffing, creating conditions every day which are dangerous for patients, Yet when we refuse to work under these conditions, we are the ones who are accused of endangering patients. A strike is a short-term hardship, but it is one which management forces into being, one which becomes necessary in order to make long-term improvements. When workers improve their job conditions they are creating a better hospital for themselves and for their patients. The same thing happens on an individual basis when a nurse refuses to take an assignment she feels she is not trained for, or refuses to put up with conditions that are unfair. In the short run, it might or might not have been better for the patient had the nurse done what she was told. But in the long run, conditions would definitely deteriorate if no action were taken.

Lastly, administrators say that strikes show that unions have destructive effects on patient care. But we’ve seen that it is administrators’ lack of concern for patient care, and their business priorities, that usually make for poor conditions. How can unions be responsible for deteriorating patient care when it is the hospital that has had control over such issues as staffing, bed space and supplies? It is in the unions’ interest, as well as in the interest of their members as health-care consumers, to improve patient care as much as possible.

>> Back to Vol. 10, No. 3 <<

REFERENCES

- Digoxin, a widely used cardiac medication

- radical bowel sugery

- Testing a diabetic patient’s urine for sugar before a meal.

- Ehrenreich, Barbara and John, The American Health Empire: Power, Profits, and Politics. New York: Random House, 1970, p. 29.

- Feshbach, Dan, “The Dynamics of Hospital Expansion,” Health-PAC Bulletin, No. 64 (May-June 1975), p. 17.

- Ehrenreich, op. cit., p. 99.

- Ibid., p. 102.

- Nichols, Bob, “Oklahoma Crude”, Health-PAC Bulletin, No. 57, (March-April 1974), pp. 1-2.

- Research by the Mount Auburn Workers’ Committee.

- Articles of Organization for the Medical Area Service Corporation, Chapter 180, May, 1972.

- Burgess, M.A., Nurses, Patients and Pocketbooks, A Report of a Study of the Economics of Nursing, New York: Commission on the Grading of Nursing Schools, 1928, p. 249. Cannings, Kathleen and William Lazonick, “The Development of the Nursing Labor Force in the United States: A Basic Analysis”, International Journal of Health Services, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1975, pp. 192-201. Reverby, Susan, “The Emergence of Hospital Nursing”, Health-PAC Bulletin, No. 66 (Sept.- Oct. 1975), p. 10.

- Burgess, op. cit., p. 332. Reverby, op. cit., p. 10.

- Cannings and Lazonick, op. cit., pp. 192-201. Reverby, op. cit., pp. 9,14.

- Cannings and Lazonick, op. cit., pp. 192-201. Reverby, op. cit., pp. 9,14.

- Ibid., p. 14.

- Burgess, op. cit., p. 442.

- Cannings and Lazonick, op. cit., pp. 192-201. Reverby, op. cit., p. 14.

- Burgess, op. cit., p. 353. From 1928: “Floor duty in hospitals is too hard and often with not enough help, and one has no time to do the little things for patients that often mean much to add to their comfort and health.”

- Reverby, op. cit., p. 15.

- Cannings and Lazonick, op. cit. Reverby, Susan, “Health: Women’s Work”, Health-PAC Bulletin, No. 40 (April 1972), p. 17. Ehrenreich, Barbara and John, “Hospital Workers: A Case Study in the New Working Class”, Monthly Review, Jan. 1973, p. 18.

- According to the February 1977 Massachusetts Nurse, pp. 3 and 6, the 1977 MNA budget allocated less than 1/3 of its non-salary expenses to the Department of Economic and General Welfare. There is no strike fund.

- Godfrey, Marjorie, “Someone Should Represent Nurses”, Nursing 76, June 1976, pp. 73ff.

- voluntary = private nonprofit.

- “Health Workers Unionize”, Dollars and Sense, No. 15, March 1976, p. 13.

- proprietary = private, profit-making.

- Information from 1199 office, New York hospital workers, etc.

- Ehrenreich, American Health Empire, p. 138. “Health Workers Unionize”, op. cit., p. 13.

- Epstein, Richard and K. Bruce Stickler, “The Nurse as Professional and as a Unionist”, Hospitals, Vol. 50, January 1976, p. 48 (footnote #10).

- Ehrenreich, American Health Empire, p. 139.

- Ibid., pp. 140-144.