This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The Lilly Connection: Drug Abuse and the Medical Profession

by Michael Smith

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 10, No. 1, January/February 1978, p. 8–15

Physicians play a crucial role in modern American society. No power of the physician has been more far-reaching than the power to determine which drugs can be “safely” given to the American public. A relatively small number of doctors have almost absolute control over the safety and effectiveness standards used in marketing drugs. In the field of drug abuse treatment, a handful of physicians control most of the important decisions in funding narcotic treatment programs, such as the multi-billion dollar “war on drugs” sponsored by the Nixon White House. Criticism of medical decisions is rarely given by non-physicians, because in some cases expertise is lacking but in many more cases because of the intimidating methods of the medical profession. To make matters worse, one of the basic lessons I was taught in medical school was that even a doctor shouldn’t criticize another doctor in public. What happens in a country where powerful figures cannot be criticized and questioned about their actions? This article is part of an inquiry into the actions and intentions of some of those medical professionals who have shaped U.S. drug abuse policy.

Physicians Facilitate Illegal Drug Sales

If we search behind the scenes of the popularized histories of drug abuse, a frightening and dangerous story emerges. In 1898 Bayer Pharmaceutical Products, the aspirin people, invented heroin, a “non-addictive” treatment for coughs, minor aches and pains. Millions of bottles of heroin elixirs and tonics were sold. Heroin was also touted as a miraculous cure for morphine addiction. Heroin was substituted for morphine in thousands of clinics. Heroin maintenance would have been an appropriate name for the treatment. A massive advertising campaign led to AMA approval of heroin in 1906. By 1910 most scientists admitted that heroin is addictive and undesirable as a common home remedy. In 1914 Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Act which outlawed most narcotics use but left loopholes just as today’ slaws often do. Up to this point we might conclude that it is tragic but perhaps excusable that the medical profession itself sold the country on one of the most devastating drugs in history. But the story continues.

In 1919, 5 years after the Harrison Act, Eli Lilly & Co. published a catalogue listing 4 kinds of heroin cough medicine- mixed with wild cherry syrup, white pine, etc. The catalogue did not mention how addicting and deadly their cough medicine was. The extra-strength brand was so powerful that 8 oz. would kill an average person. Lilly’s Glycerole Heroin Compound, for instance, was supplied in pint and gallon bottles.

How could the doctors and pharmacists at Lilly have made such a decision? Was the need for cough medicine so great that they chose to take the risk of accidental overdose and the associated bad publicity? It makes one very suspicious that their real intention was to supply the booming illegal market in heroin at that time. We now know that Lilly has repeated these suspicious marketing techniques with a series of dangerous, addictive drugs—Seconal, Tuinal, and Methadone.

Immediately at the end of World War II in Europe, a Lilly research chemist named Dr. Ervin C. Kleiderer joined the Technical Industrial Intelligence Committee of the State Department which was investigating Nazi drug companies.1 Kleiderer’s team brought methadone to this country. Two years later Lilly marketed Dolophine cough medicine, retaining the Nazi brand name for methadone which had been chosen to honor Adolph Hitler. Kleiderer soon became Executive Director of Development at Lilly. Lilly sold methadone cough syrup and tablets for 25 years, until the 1970s. It was supplied in pint and gallon bottles. Four ounces or four tablets would kill an average person. Does that sound familiar? Why would Dr. Ivan Bennett, the director of clinical research, and other medical professionals at Lilly take such a risk of malpractice? Methadone was never heavily advertised as a cough medicine. Federal researchers at Lexington, Kentucky had given it a bad reputation in 1947 by demonstrating how addictive and potentially fatal methadone is.2 Despite this, methadone was slowly seeping out into the lucrative illegal drug market. It would only be a matter of time before some miracle-seeking doctor would “discover” that methadone could be used to treat heroin just as heroin had been used to treat morphine. In 1972 Lilly produced 90% of the methadone used by the tens of thousands of maintenance clients and the equal number of illicit users.3

Propoxyphene, known as Darvon, is the latest addition to Lilly’s narcotic family. Chemically very similar to methadone, Darvon was marketed since 1958 as a treatment for headaches and minor aches and pains. It has been phenomenally successful, accounting for $100million in yearly sales for Lilly. Darvon was tested by narcotic researchers at Lexington in 1960 and found to be addictive and potentially fatal, yet paradoxically no more effective than a sugar pill for relieving pain.4 Darvon has always been used on the streets to get high and to maintain a narcotic habit. Medium-sized cities like Ft. Worth or Oakland have consistently reported 30-40 Darvon-related deaths each year.5 Most cities do not keep such statistics. Darvon death reports have been printed in the Wall Street Journal, because Darvon profits have been the keystone of Lilly’s 20% yearly increase in profits; but these reports have been kept out of mass circulation papers, because the public might learn what is really going on.

As the 17 -year patent on Darvon was running out in 1971, Lilly “invented” propoxyphene napsylate, or Darvon-N, a nearly identical compound that could be exclusively patented for another 17 years. In 1973 Lilly’s Dr. Bennett called a private conference on Darvon-N with top drug abuse officials in Washington. He proposed that Darvon-N maintenance might be able to replace methadone maintenance. Dr. Forest Tennant, who has run several drug clinics in poor communities in Los Angeles, stated that Black drug victims in Watts and young white victims in San Francisco have heard so many bad reports about methadone that they are refusing it for treatment. He explained that Darvon-N “helps us treat the thousands of addicts who don’t find methadone acceptable.” A free-clinic doctor in San Francisco called Darvon-N “the hottest drug of the century.” Regular side effects from Darvon maintenance include headache, rapid pulse, feeling spaced out, hyperactivity, weight gain and persistent insomnia. Darvon maintenance has been used widely in California, but fortunately this latest narcotic bonanza has failed to spread.

In each of the last 20 years Lilly has produced billions of its barbiturates, Seconal and Tuinal, which have found their way into the illegal drug market. Lilly officials have been called before a number of House and Senate committee hearings to explain why they overproduce these “sleeping pills” which bring in $5 billion in street sales yearly.6 The answer is almost inescapable. Eli Lilly & Co. systematically markets addictive drugs. Under the direction of physicians such as Dr. Ivan Bennett, Lilly has developed a variety of legal and illegal tactics to sell the maximum number of addictive drugs and gain the maximum profits in the process.

Cover-Up of Methadone’s Dangerous Effects

Methadone maintenance has been the most expensive and far-reaching medical treatment program ever financed by the federal government. The physicians entrusted to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of this program have been for the most part the very doctors who run the maintenance programs and who thus have a vested interest in keeping things quiet. For instance, Dr. Mary Jeanne Kreek of Rockefeller University, where methadone maintenance began, has reported in many articles that methadone maintenance is “medically safe, with minimal side effects and no toxicity.”7 She reports 14% impotence, but as one methadone program physician stated recently, “that’s one of the side effects people have to learn to live with.” Since insomnia cannot be measured by laboratory tests, Kreek minimizes this common effect of methadone maintenance. She never mentions the fact that pronounced edema and tissue swelling causing 20 pounds and more of weight gain occur in 5% of maintenance patients (by our estimates). Countless other complaints are passed off as “subjective” and unverifiable scientifically.

Methadone is five times as deadly as morphine in equivalent doses when tested on rats.8 Methadone related overdose deaths outnumbered heroin-related overdose deaths in Washington, D.C. as early as 1971.9 Heroin overdose is treated by 1-2 injections of Narcan, the narcotic antagonist. Methadone overdose victims may require up to 20 injections of Narcan, given at 2-hour intervals. One patient at Lincoln Hospital died because he did not receive his 17th injection of Narcan. In 1974 I was a lecturer to emergency room staffs in New York City for the State Health Department, and in my experience, almost none of the physicians and nurses were aware of how to treat methadone overdose victims. Based on my experiences in New York City, I would estimate that at least 50 young people have died of methadone overdose in that city solely because medical personnel had not been informed about the proper treatment protocol. Since methadone has been on the U.S. market for nearly 30 years, how could such an oversight occur? Evidently, the government health agencies and Lilly Co. have made very little effort to teach medical personnel how to treat methadone overdoses.

For example, in 1972 the New York City medical examiner Halperin suppressed any further announcements of methadone-related deaths “because the publicity is damaging to city-sponsored programs.”10 The consistent record of issuing falsely positive information about methadone in both the public and the private sector leads one to assume that the information regarding treatment of methadone overdoses was probably deliberately withheld. Had medical personnel known how deadly methadone is, it would have been a blow to methadone sales.

The doctors who created the theory of methadone maintenance at Rockefeller University, Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander, still claim that it is “relatively easy” to withdraw from methadone.11 During the first public discussions of methadone maintenance in 1967, the New York Times in· its daily dispatches never once mentioned that this new “heroin cure” was itself highly addictive.12 Rockefeller University methadone supporters were able to blanket the media with favorable reports. Today almost all medical observers who are not biased by working in methadone programs agree with the complaint that methadone patient-addicts have made for years: methadone is much harder to kick than heroin. The research division of the New York State Office of Drug Abuse Services told us that their primary goal for 1976 is to develop effective means of detoxifying methadone maintenance clients.

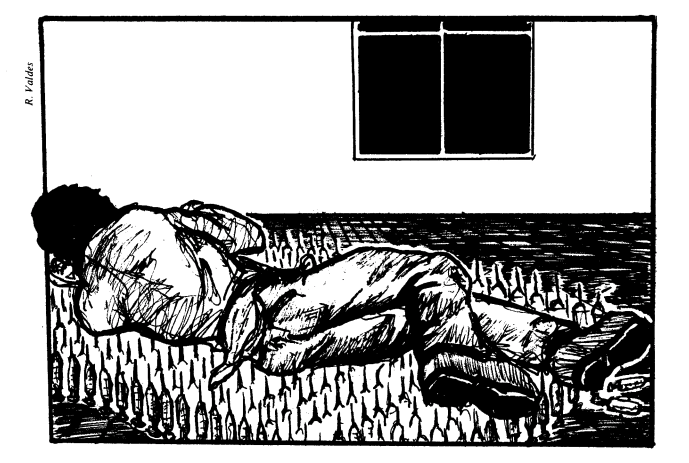

Withdrawal from methadone addiction is a long, drawn out, brutal experience. There is no two-to-five-day crisis of vomiting and tremors as with heroin. During withdrawal from methadone the following problems occur: insomnia, depression, “bone pains,” sweating, hot and cold flashes, intestinal disturbances, and the sensation of being unable to move your limbs. These symptoms occur for weeks and usually months on end. We have observed many well motivated people be unable to detoxify due to the prolonged anguish of gradual withdrawal from methadone.

The most bizarre and horrible effects of methadone withdrawal occur in infants born to mothers who are addicted to methadone. Dr. Rajegowda and Dr. Stephen Kendall reported the following study at the National Drug Abuse Conference in New Orleans in April 1975. Out of 187 methadone babies born at Jacobi and Lincoln Hospitals in the Bronx (in 1973-74), eight babies died of crib-death between two and six months of age. These methadone babies died of crib-death at 17 times the normal rate. Their mothers had no chance to help them survive. The babies died in their sleep with no warning. Medical examinations prior to death showed no changes in symptoms or other signs that might have predicted which of the 187 babies were going to die. No cause of death was found on autopsy.

A previous study w·as done at the Yale University School of Medicine and was reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association on June 26, 1972. At Yale three out of the 15 babies died of crib-death before three months of age. Heroin-addicted babies do not have as many withdrawal symptoms as methadone babies, and heroin is not associated with a higher rate of crib-deaths. With the exception of Thalidomide, none of the hundreds of drugs which have been outlawed by the Food & Drug Administration has caused such a frightening level of human infant mortality as that reported for methadone in these two studies.

Both the Bronx and the Yale study were sponsored by agencies which run large methadone maintenance programs. Their statistical methods were able to be very straightforward and thus inherently more reliable than most medical surveys for adverse reactions. Methadone clients report to their program, and these babies were followed by the pediatrics departments of the same hospital as the methadone program. It would be very easy for any city health department to verify whether methadone babies have an unusually high death rate, since information on all methadone clients and all birth and death records are kept in those agencies. As fantastic as it might seem, this kind of statistical analysis has not been published. Most studies we have seen about methadone and infants evaluate withdrawal symptoms only while the child remains in the hospital. Comments are rarely made about the crib-death phenomenon in most of the studies.

We have spoken with a number of methadone maintenance clients whose babies died mysteriously in the first year of life. None of them were aware that their child’s death might have been caused by methadone. They had not complained or sought further information when the doctors told them the children died “of unknown causes.” Most of these mothers were afraid they had neglected their children in some unspecified way and hence they preferred to act as though the tragedy had never happened.

What fears do the doctors who run methadone maintenance programs have? For what reasons has information regarding methadone and crib-deaths been actively suppressed? Dr. Joyce Lowinson runs the 2,400-patient Albert Einstein College of Medicine methadone maintenance program in the Bronx. Yet she has not refuted or acted upon the study that her own institution sponsored which shows disastrous infant mortality. This is a glaring example of the double standard that exists in U.S. health care. Middle-class women are encouraged to avoid any medications that even might cause birth defects. In contrast, women who are seeking treatment for drug addiction are encouraged to take large amounts of methadone which has been closely associated with alarming infant mortality. Most of these women on methadone are not even told about the risk they are taking. This situation is also a glaring example of the bankruptcy of professional ethics on the part of those physicians who direct methadone maintenance programs.

I have described a widespread medical cover-up of the risks of methadone treatment. In spite of methadone directors’ complaints that federal agencies harass their programs,13 exactly the opposite is the case. The federal government has supported and protected methadone more than any other health treatment- of any kind- in U.S. history. More funds have gone to methadone than to any other medical treatment. In 1972, when the FDA gave its final approval for massive use of methadone maintenance, methadone overdose deaths already outnumbered heroin overdose deaths in the nation’s capital. Of 560 drug abuse grants listed in the federal Research Grants Index for 1974, only 19 mention methadone in their title. Most of these studies concern what will happen to rats and guinea pigs. Very few of the research studies explore what has already happened to the hundreds of thousands of human methadone addicts. These research policies of the National Institute of Drug Abuse certainly suggest that official ignorance about the effects of methadone will continue.

Physicians’ Greed

Two reasons can be suggested for certain doctors’ unquestioning loyalty to methadone: 1) greed, and 2) the desire for social power. Greed has been a traditional cause of medical malpractice throughout history. From 1970 to 1974, 24 private methadone maintenance clinics sprang up in New York City. According to investigations by City Councilman Carter Burden and the Village Voice,14 these programs net a total of $2-3.5 million in profits each year. The private methadone clinics all have a doctor as a front man, as required by law. The real owners often include construction contractors, wholesale jewelers, and real estate agents- classes of people who often have strong underworld connections. This coincidence might explain the remarkable safety record that all methadone clinics that we know about have maintained. If any person tries to undersell the established heroin dealers in a neighborhood, his or her life could be forfeited. Yet this is exactly what public and private methadone clinics do: they offer a cheaper narcotic than heroin. What has been the reaction of large heroin sellers to this apparently huge loss in business? Nothing. No methadone clinics have been firebombed or terrorized out of business. How could these organized crime czars be so calm about methadone and yet be so willing to murder people in penny-ante extortion rackets? Only one answer seems possible: payoffs, either directly as protection money to underworld bosses, or indirectly, through “legal” returns on business investments, to these same bosses. Of course, such legal returns on business investments also accrue to wealthy and respected leaders of the country through, say, real estate holdings, but that’s another story.

There is a script doctor in most neighborhoods who will prescribe harmful and addicting drugs for a price. And there is along tradition of payoffs from the pharmaceutical companies to the medical profession. In fact, Eli Lilly & Co., the leading producer of methadone and barbiturates, is also the leading provider of gifts and travel expenses to young doctors and pharmacists.15 However, the possible relationship between organized crime and the methadone business- both maintenance programs and the corporations that leak drugs on the street—suggests a new and more devastating level of corruption that physicians may be involved in. By using the medical profession and the pharmaceutical industry, organized crime could be gaining a further stranglehold on our lives.

The Use of Drugs by Physicians for Social Control

In my opinion the most dangerous aspect of physicians’ involvement in the U.S. drug abuse policy is promoting the use of drugs to control people against their will. First of all, individual daily records on all methadone maintenance clients are registered in several computer systems. Methadone clients in New York City are registered in city computers and also in the computers of a private organization, the Community Treatment Foundation, which is a subsidiary of Rockefeller University. One justification of the computerization is research. Yet high officials in the city Health Services Administration methadone section told us recently that they are aware of no research studies that have been published using Rockefeller’s computer data. Another justification of the computerization is protection against clients signing up for more than one program. The necessary precautions in this regard could be accomplished by just using the city computer systems. It is hard to conceive of any valid justification which would require multiple computer systems or the use of private computer systems. One of the basic principles of medical ethics is total confidentiality between doctor and patient. Yet Dr. Vincent Dole, who was the co-founder of methadone maintenance at Rockefeller, has always been a foremost supporter of the computer systems.

Few of us have to be reminded how computer intelligence has been misused in recent times. The following report in the Atlanta Constitution (6/24/71) tells the story: “Carter met with Dr. Robert DuPont … who heads the District of Columbia’s 16 month old methadone program . . . DuPont showed Carter the District’s computer center . . . A treatment aide pressed a few buttons linked to a system in Boston and retrieved the name of a Washington addict named Jimmy Carter, who began the use of heroin at the age of 15.” How can that Jimmy Carter of Washington be sure that credit bureaus, law enforcement agencies, potential employers and the like do not have access to that computer in Boston? Dr. Robert Newman of New York City was asked to search his files by the District Attorney. Newman refused and his decision was finally upheld by the Supreme Court. Nevertheless, it is difficult to imagine a system of record keeping that is more prone to abuse than the methadone computer system. Richard Nixon’s Special Action Office funded the system. Would he have tolerated any hesitation about leaking this information for the White House benefit?

Most methadone maintenance programs offer counseling and some kinds of therapy. In some instances we know that this counselling has been constructive and that a number of people on maintenance have been stabilized and improved their lives despite the obstacles involved. However, in the majority of instances the main ingredient in this kind of “therapy” is the open or veiled threat: obey the staff or get off the program. The threat of sudden methadone withdrawal or having to hustle drug money on the street again is very powerful. At first the victim is usually suspended for 3 days, just long enough for methadone withdrawal to begin to be felt. In addition, the clients’ welfare and parole status often depend on continued good standing in the maintenance program. Furthermore, the computer link-ups and agreements between the programs make it easy for expulsion from one program to mean expulsion from all programs if the program director wants it that way. As every street addict knows, you don’t dare cross the pusherman, even if he happens to be kindly old Uncle Sam.

I worked as a part-time psychiatrist in the Bronx County Jail for several years. A large number of inmates were offered the opportunity of parole to a methadone maintenance program as an alternative to a prison sentence. Sometimes it meant the chance to avoid up to 5 years in jail. In spite of my views on methadone, I never discouraged these men from taking what seemed to me at the time to be clearly the better of two evils, parole onto methadone. I was startled to learn that many of these prisoners chose to remain in jail for several years rather than take their chances on methadone maintenance. Need I say that these men hated being in prison and missed contact with their families very deeply. The prisoners I am referring to did not know most of the details about methadone that we are discussing today. They did not consider refusing methadone as a particular moral or political commitment. But they knew from street experience what methadone maintenance was all about and chose to do their time in a four-walled jail instead.

One doctor in Chicago is trying to perfect the manipulative aspect of methadone maintenance. He is Dr. Jordan Scher, the executive director of the National Council on Drug Abuse, director of the Methadone Maintenance Institute (MMI), and a visiting professor at the University of Miami. MMI has advertised that it could set up methadone maintenance clinics in any community that wanted one on a package basis. In a recent article Scher states the “conditioning nature of methadone … is insufficiently exploited. The patients are getting something they want in exchange for something we want.”16 For example, MMI requires complete obedience to rules about dress and length and style of hair. In many parts of the country programs have harassed methadone clients who wear Black liberation buttons and demonstrate political beliefs in other (legal) ways. Women with a developing feminist consciousness and gay people have also been frequently harassed.

The most powerful encouragement for this type of coercive “therapy” has come from Dr. Peter Bourne. Bourne has repeatedly praised the addictiveness of methadone, saying that this quality of addictiveness “helps trust develop between the patient and the doctor.” Examine the instructions he gives on page 5 of the Methadone Maintenance Treatment Manual prepared by the Department of Justice and the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration:

At the center, the patient is exposed to all of its rehabilitation services, including his relation with his counselor … which can evolve into one of trust and intimacy with considerable therapeutic potential. The fact that methadone is addictive is essential to allow this to occur. Many addicts have difficulty establishing close relationships and were it not for the fact that they were addicted, they would find it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to return reliably on a daily basis and establish an ongoing relationship with the personnel of the clinic.

The addicting nature of methadone, in short, “provides the critical element in allowing the establishment of a relationship with the addict with all of its therapeutic, rehabilitative potential.” A non-addicting substitute for methadone would lack this essential characteristic. As director of Drug Abuse Services in Georgia, Bourne established what he proudly admits was the most rigid computerized system of methadone maintenance in the country. He was chosen to be the only doctor in the state to have the power to prescribe methadone. Shortly after Bourne wrote a medical journal article praising the addictiveness of methadone, he was promoted to be second-in-charge of Nixon’s Special Action Office on drugs. Dr. Bourne is now head of Carter’s office on drug abuse.

The overall picture of methadone maintenance is frightening in its potential for social control. Using the methadone computer system, one can locate any of the hundred thousand methadone clients in a moment’s notice. The dose of methadone that a certain client is taking, the name of the program director, and important background information is provided. In the name of “therapy” that program director could be asked to encourage the client to cooperate with police authorities, to provide information about certain community activities, or to perform whatever task might be deemed in the “public interest.” It is not important that we cannot document a case where this has happened; it is doubtful that we would know if it had. It is extremely important that a system so rife with potential for abuse exists, with no controls on its originators and operators.

Schemes for social control are not described in the laws authorizing methadone maintenance which Congress passed. The critical aspects of the program—(1) massive computerization and (2) “therapeutic” use of the addictiveness of methadone- were developed by physicians who claim to be acting in the interests of their patients. I know of no safeguards or watchdog agencies which could protect against the coercion of methadone maintenance clients for purposes of social control. This expanded role for physicians, that of hit man for the forces of law and order, is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of methadone maintenance, since there are no institutional restraints on them whatsoever.

Physician, Heal Thyself!

My remarks here are a considerable indictment of physicians’ actions in the area of drug abuse. Let me conclude by mentioning the positive actions that a few physicians have taken and must continue to take in our fight against drug abuse in America. First of all, there must be a primary concern for the drug abusing patients’ welfare. Drug addicts are victims of the drug that they abuse, and in many ways they are victims of society as well. The people most likely to turn to drugs are the people at the bottom of the ladder- who live in the worst housing, go to the worst schools, and get the worst jobs, if they get any at all. They seek some pleasure, a kick, a high, anything that will make them oblivious in a world of too much pain. Victims of drugs who are trying to seek help are harassed in numerous ways by medical institutions and other sectors of society. At Lincoln Detox we have been advocates for drug victims in thousands of situations where we were seeking just the bare minimum of health care and found endless roadblocks in our path. How many drug abuse programs take an active concern in improving their clients’ health care? We have found that community-run programs almost always have this priority, but in our experience programs run by physicians—by and large methadone programs—have a very poor record in this regard. It takes considerable patience and energy to cope with drug victims’ health needs, but if we are helping people to rehabilitate themselves, there is no other way to proceed.

Secondly, physicians must discard chemical and psychoanalytic approaches to drug abuse. It is simply absurd to compare methadone with insulin. It is equally absurd to say that individual “character disorders” caused drug abuse among 700,000 GIs, for instance. These issues have been discussed many times, and I do not have space here to go into detail in these matters. Drug abuse is primarily a social problem and can only be alleviated by socially-oriented solutions. In these areas the physician does not have any expertise. Therefore he or she must function as a student· or an assistant to other more knowledgeable people in order to have any positive effect on the drug abuse epidemic. When doctors in drug abuse programs have not taken criticism and advice from community people, including ex-addicts, the results have been consistently disastrous. The fact that this humble and rational response has rarely occurred among physicians is one of the main reasons for the failure of U.S. drug abuse policy.

At Lincoln Detox we have sought alternatives to the seemingly endless cycle of chemical “solutions” to drug abuse. We have used acupuncture for four years and have now used herbology for one year as well. When I first saw people sitting around the room with acupuncture needles in their ears, I couldn’t help thinking that it was all some kind of hoax. It isn’t. Acupuncture has proven to be a very valuable tool in eliminating the physical problems of drug withdrawal and rehabilitation.

The final qualities I will refer to which are essential in combatting drug abuse are courage and a will to win. Drug abuse certainly does mean warfare. In addition to the casualties among actual victims of the drugs, there must be thousands of deaths each year due to the cutthroat competition between various dope dealers. Anyone seriously opposing these ruthless dealers should expect the same kind of treatment.

In every poor neighborhood in America certain individuals or small groups of people have stood up to the drug bosses in their area. We would do well to honor these people on a memorial day. One of these honored dead is Dr. Richard Taft, who worked for the Lincoln Detox program. On October 29, 1974 Richard was found stuffed in a closet, shot up with heroin on the morning he was to meet with a powerful Washington official about funding our acupuncture program. As an alternative to methadone and as part of a people’s program against drug abuse, the Lincoln Detox acupuncture program has been very threatening to those who want to expand the drug-pushing business. Richard’s death has never been seriously investigated by the police or by any of the drug abuse agencies we are involved with. Further harassment and incidents have occurred after his death.

But the Lincoln Detox Program has continued. Our approach can be outlined as follows:

(1) Supportive assistance to the victims of drug abuse, who include the drug users, their families and neighbors, and the people who have suffered as a result of drug-related crimes. Build the physical body with nutrition, exercise, and natural-healing techniques such as acupuncture and herbology so that the life energies can become strong again. Helping the body become strong enough to excrete toxic substances is very different from substituting one drug for another. Psychologically and socially, we need education, spiritual encouragement, supportive counselling, and group-centered work which focuses on coping with day-to-day anxiety-producing reality and working to change that reality. This approach contrasts with analytic, individualized and often negativistic therapy aimed at “adjustment” to bad conditions, and it is opposed to mindless welfare-oriented methods.

(2) Seriously attack the corruption and apathy which protect major heroin dealers. If you want to find the people who control heroin traffic, look only among the ranks of millionaires. In truth, heroin traffic has never been outlawed in the United States. Those at the top who plan and direct heroin traffic have never been injured by the law. The criminal justice system has only punished the victims of the heroin plague. Drug users should be dealt with supportively. Major drug importers and sellers should be dealt with harshly.

(3) Sweeping changes in society are necessary in order to destroy the soil which nurtures drug addiction. There are enough problems in our society and enough work that needs to be done so that meaningful jobs should be available to everyone. Dignity with regard to racial, sexual, and cultural identity must be respected. Senseless wars such as the Vietnam conflict must be opposed. These issues are direct major causes of drug addiction; they cannot be shoved aside as peripheral social issues. Most of us have been taught to separate protest about social issues from individual treatment. These habits have crippled our efforts. To be effective at any level of drug abuse prevention or treatment, a person must maintain integrity- a difficult task in a complex society. To criticize weaknesses in a drug user and not criticize the weaknesses in society that cause drug abuse only worsens the situation. Drug abuse is more a disease of society than of the individual. The task before us is to cure society.

Michael Smith is the medical director of the Lincoln Detox Program, which is a community-based drug program in the South Bronx, New York City. The program is the largest ambulatory (walk-in) detoxification program in the country and has the largest acupuncture drug abuse treatment component in the country. This article is adapted from testimony he presented at the National Hearings on the Heroin Epidemic, Washington, D.C., in June 1976.

>> Back to Vol. 10, No. 1 <<

REFERENCES

- Cited in Methadone Maintenance Treatment Manual by LEAA (Dept. of Justice).

- Cited in Jerome Jaffe’s section on narcotics in Goodman and Gilman, ed., Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 3rd edition, MacMillan, 1966.

- Cited by Rep. Charles Rangel in his statement before the Methadone Use and Abuse Hearings before the Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency of the Committee on the Judiciary of the U.S. Senate, 92nd and 93rd Congress.

- Most information concerning Darvon taken from “Another Methadone Thing?” Connection. volume II, numbers 4-6, Institute for Social Concerns, Oakland, Calif. Feb-April 1974. Project funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- Same as above.

- Pekkanen, American Connection. Follet Publ. 1973.

- Kreek, Mary Jeanne, “Medical Safety and Side Effects of Methadone in Tolerant Individuals,” Journal of the American Medical Association. 223:6, Feb. 5, 1973.

- Merck Manual, a standard medical reference work.

- Markham, James, “The Heroin Epidemic,” New York Times, p. 28, Oct. 21, 1972.

- Announced at a press conference on Nov. 10, 1972, given by Health Services Administration Commissioner, Gordon Chase.

- Dole, Vincent and Marie Nyswander, “Methadone Maintenance Treatment: A Ten-Year Perspective,” Journal of the American Medical Association. Vol. 235: 19, May 10, 1976.

- Cited in Rep. Charles Rangel, op. cit.

- Dole & Nyswander, op. cit.

- Village Voice. April 18, 1974.

- Testimony by Martin Shangel and others in Examination of the Pharmaceutical Industry. Hearings before the Kennedy Senate Health Sub-committee, 1973:74, pp. 732,754, 1293, 1419-23.

- Scher, Jordan, “Methadone Maintenance: Two Cities’ Experience,” Drug Forum. Vol. 3, Fall 1973, pp. 75-76.