This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Making the Unthinkable Appear Routine: War of the Wards

by Marilyn Flower & Liz Jacob

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 14, No. #3 May-June 1982, p. 8-14

Marilyn Flower is a trade union activist in SEIU Local 616 in Oakland California; and she is currently fighting Reaganomics with the Alameda County Labor-Community Coalition. Liz Jacobs is a long-time health care worker, currently a nurse at the Native American Health Center in San Francisco, California.

The Department of Defense is seeking the assistance of the civilian health community to temporarily supplement its medical capability for future wartime needs.1

An integral part of U.S. war preparation is the Civilian-Military Contingency Hospital System (CMCHS). CMCHS was created under the Carter Administration in early 1980, and fits neatly into the beginnings of a shift in spending priorities from social services to the military. Specifically, it is a patriotic call to duty by the Department of Defense (DOD) to civilian hospitals nationwide (with greater than 150 beds) to reserve a minimum of 50 staffed beds to provide the medical support for a “future major conflict outside the United States.”2 The Department of Defense is asking hospital administrators to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (M.O.U.) which is a non-binding agreement ackowledging participation.

There has never been a plan like this in the history of this country. Civilian hospitals have never been asked to prepare for war before a congressional declaration. It is modeled after a similar Israeli plan to use civilian hospitals for quick expansion of military services in times of disaster or “sudden…short and violent wars.”3 According to James Doherty, an American hospital official on loan to the Pentagon, CMCHS is an attempt to prepare for a potential large scale conventional war or a confrontation involving tactical nuclear weapons in Europe or in the Middle East or both.4

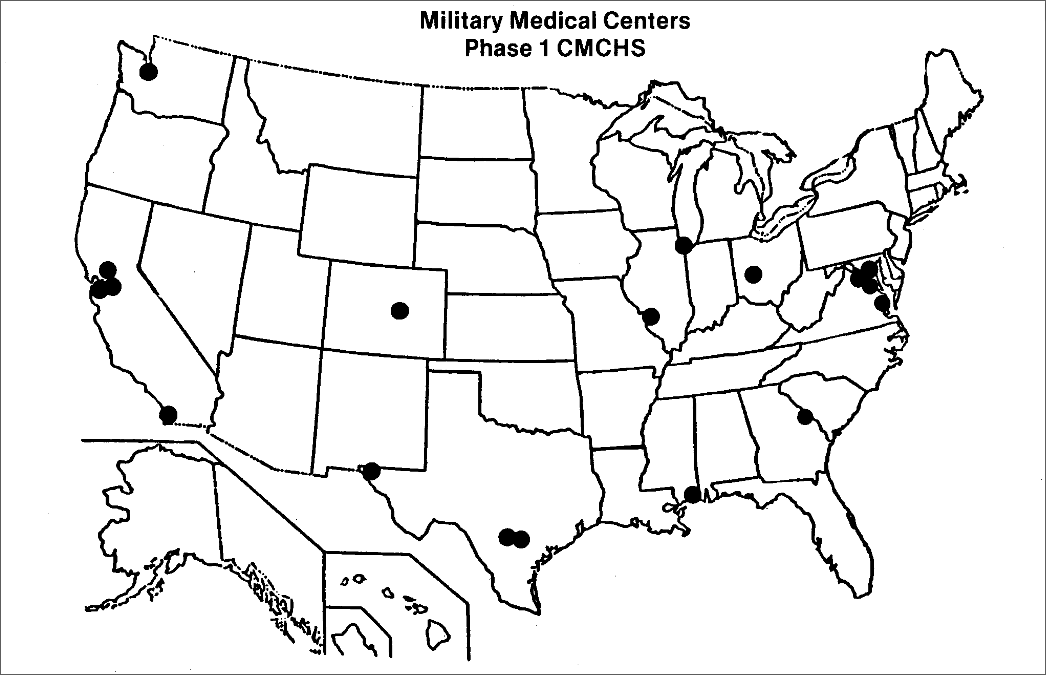

There are three phases to the unfolding of this atrocity. As part of Phase I, 17 cities nationwide have been targeted, based on their strategic importance and proximity to military medical centers (see map). The goal of Phase I is to commit 50,000 civilian beds to supplement 15,000 existing military beds. Phase II goes after hospitals near smaller military facilities and Phase III targets medium to large urban medical centers. The goal of these final phases is 100,000 additional beds. As of October 1981, 19,000 beds had already been “pledged.”

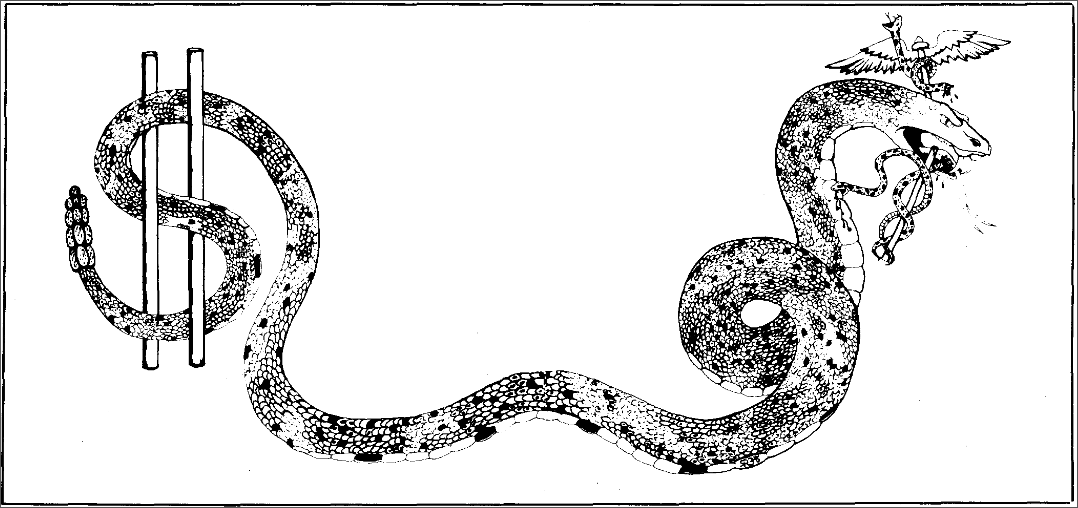

CMCHS can only be understood in the context of recent trends in U.S. foreign policy. The “Vietnam Syndrome”5 has been overshadowed by an increasingly belligerent U.S. foreign policy. The U.S. is now frantically attempting to strengthen ideological and military superiority over the Soviet Union and national liberation movements, in order to turn back the successes of struggles in Central America, Africa, and the Middle East. It is clear that U.S. foreign policy is a war policy based on imperialist intervention and nuclear threats.

Witness the many illustrations of this increasing war threat and the consequent militarization of U.S. society. Social services won through 50 years of struggle, have been sacrificed to an already crippling military budget. U.S. military and economic aggression have escalated against Cuba, Nicaragua and the liberation forces of El Salvador. Administration pronouncements support the idea that the U.S. is planning to engage in a “limited” nuclear war in Europe. U.S. military might has been displayed through provocative war games such as “Operation Bright Star” in November 1981, in which 5000 troops engaged in a mock battle in the Middle East.

CMCHS is more than a means for the military to acquire a back-up medical system. It starts with a military briefing for hospital administrators, complete with slides of Soviet tanks, tables and graphs of bed availability and casualty rates. Then, with a 50 page plan, U.S. aggression is spoonfed to hospital administrators and health workers as the challenge of “saving lives together.” The entire operation is based on the premise that “the Soviet Union’s awesome military power poses a threat to the United States” — although the report also assumes there will not be an attack on the U.S. homeland.6 This is not a defensive plan to be used in case of attack.

Grim Particulars

The minimum commitment for CMCHS is 50 “normally occupied” beds which could be commandeered in 24 to 48 hours, or with no notice at all. Beyond beds, the military will need surgery and intensive care units, blood banks, respiratory therapy equipment, x-ray machines, laboratories, emergency rooms, pharmaceuticals, physical therapy facilities, and support services such as food supplies and nursing.

Hospitals joining CMCHS must complete a questionnaire detailing age, sex, military affiliation and draft status of hospital staff; submit daily bed availability reports to local military liaison officers; and appoint two staff members — one administrative and one medical — to coordinate operations with the military. (“Plans must be developed within your institution, refined, and tested to ensure that the system could be successfully implemented on short notice.”)7

To test a hospital’s preparedness, participation in annual drills with the military is required. “You will be expected to commit sufficient resources to the exercise to ensure that key staff personnel including physicians become thoroughly familiar with the system, prepare a critique, and make necessary changes (in it).”8 This drill may also include triage (sorting) of casualties at the landing site, presumably military bases. Through CMCHS the military bypasses the usual draft of individuals to draft institutions in which individuals have no recourse for objection or appeal. There are no provisions for conscientious objectors.

Although the plan is designed to acclimate hospital staff and the community to military control over civilians and civilian institutions, there is no mention of consulting hospital workers or their unions about the dramatic changes required in administative and working conditions. According to the National Lawyers Guild, the implementation of these changes, without contract negotiations, is in clear violation of National Labor Relations Board regulations, and can be contested on those grounds.

The envisioned scale of civilian involvement in war preparations goes well beyond hospitals. Military medical commanders will be “establishing liaison with local civilian agencies which have the capacity to supplement the military health system… for example, Emergency Medical Services Systems (EMSS), fire and rescue services, mass transit services, communications centers and others.”9

The DOD has two goals with CMCHS. The first is to anticipate needs for military hospital services which match an increasingly aggressive U.S. foreign policy. It is already understood that military hospitals cannot now handle the massive casualties resulting from the various war scenarios being planned — particularly “limited tactical” nuclear wars. Further, because the President is given the power to declare a state of emergency at any time and to requisition hospital beds, CMCHS permits rapid response without the necessity of a Congressional declaration of war.

The second, possibly more significant, role of CMCHS is in the psychological preparation of the U.S. people for war. War in this mental framework becomes viewed as a realistic and acceptable possibility, so it is best to be well prepared. In turn, war preparedness legitimates and enhances the ability of the government to threaten other nations with war.

Hospitals joining CMCHS are encouraged to make their stand known publically, with the DOD doing likewise. The plan includes a substantial press release for hospitals’ use. Accordingly, one of the benefits to participating hospitals is public relations: “the public will enthusiastically support a well organized, professionally coordinated opportunity to participate directly in the national defense effort.”10 However, no hospital on the West Coast has voluntarily publicized its choice to participate, for whenever the plan has been subjected to public scrutiny, opposition has been massive and broad-based.

Another “benefit” CMCHS offers health workers is “staff challenge.” “The types and severity of injuries and illnesses which are anticipated from the combat zone will present a challenge to your hospital staff, and there would be no question about their direct involvement in the support of the national defense effort.”11 The plan even includes a “national patient profile” summary giving 100 likely injuries and diseases with which the medical staff will be challenged.

Given the premise of the CMCHS plan — that the next war will feature the latest weaponry and that casualties will be astronomical — a likely scenario is nuclear war. In fact, Dr. Moxley (DOD’s former medical chief) responded to direct inquiries by stating that, ”This does not rule out the possibility that such a war could escalate to a tactical nuclear exchange and planning must, of course, consider that possibility.” The “national patient profile” lists 11 severe burn cases which could well represent radiation victims. No doubt in an actual nuclear war the percentage would be far higher than 11, and would probably be so high that medical assistance would be virtually meaningless. There is no mention of this in the plan even though health care providers have publically criticized the assumption that they can medically treat radiation injuries in a nuclear war. Nevertheless, President Reagan operates under the assumption that a “limited” nuclear war can be waged with a minimum of risk. This assumption, which also underlies CMCHS, makes CMCHS inseparable from current U.S. foreign policy, which attempts to make war (even nuclear war) viable, if not acceptable.

Impact on Health Care

The question most asked about CMCHS is, “What happens to the patients using the 50 beds when war breaks out?” There is no civilian contingency system in the plan. The plan explicitly states that the 50 to 150 beds will be “normally occupied” beds; increased casualties may require expansion into unused beds. It is true that many hospitals are “overbedded.” This is because there is a tendency to build medical complexes in affluent communities where there is a building cash flow and municipal tax breaks. Especially in suburban areas, the number of beds are so high that the hospitals are actually in competition for the lucrative insured patients. But while there may be extra beds, they are not usually staffed or serviced. Changes would have to be made to utilize them.

In contrast to suburban areas, most urban hospitals have fewer staffed beds than are needed. The average urban hospital is likely to be filled or nearly filled with patients, with overcrowded clinics and waiting rooms. Low wages and poor working conditions, archaic administrative practices, forced overtime, professional disrespect, racism, sexism, and other such problems are factors in the chronic understaffing of these hospitals. Under CMCHS, these personnel and bed shortages will be further taxed, and facilities may even be taken out of public use. The result would be dangerous both to displaced individuals and to the community that has had its health services drastically reduced. In the case of public hospitals, which are often the only facilities that will treat Medicaid and “medically indigent” (working poor) patients, the displacement may mean no care at all.

Since most urban hospitals serve poor or minority communities, the greatest impact of CMCHS will be the removal of health services from groups historically given the least adequate care. Racist patterns of health care delivery will be exacerbated by CMCHS. As one county hospital patient put it at a recent CMCHS hearing in Oakland, California, “Instead of coming here and taking our only beds, the Federal Government should see the state of emergency we’re in. They should send doctors and nurses to come here and help meet the needs of our suffering communities instead of the other way around.”

CMCHS was introduced to West Coast hospital administrators at about the same time Reagan began his cuts in social spending which helped finance the inflated military budget. Some of these cuts have a direct impact on federal and state reimbursement for health services, such as those in Medicaid and Medicare. Others have an indirect impact by making people more vulnerable to disease, such as cuts in food stamps and the WIC (women, infants and children nutrition) program. With these cuts, infant mortality, birth defects, and children’s diseases in poor and minority communities will rise.

Hospitals, then, will be faced with greater health care needs with fewer sources of funding and reimbursement. During the last decade, public hospitals have been closing at an alarming rate. New York City, for instance, used to have 25 public hospitals, it now has only five. And as states toughen Medicaid eligibility to conform to lower federal subsidies, as high unemployment continues, and as community health centers close, there will be an ever greater demand for low cost (or totally subsidized) health services.

CMCHS may appeal to opportunistic hospital administrators looking for a way out of financial problems. No doubt the DOD would have a stake in the closure question of hospitals signed up with the plan. No doubt the possibility of full-paying military patients looks attractive at this time. For public hospitals the possibility of conversion into a military facility is increasing: San Francisco’s U.S. Public Health Hospital, for example, was recently closed only to reopen as a military hospital.

Through CMCHS, DOD has “civilianized” its responsibilities towards war veterans. While the Vietnam veterans’ struggle for recognition and treatment of long term effects of the last war continues, contingency plans unfold for the next war. The money going into the military budget at an unprecedented rate goes for weapons, war technology, defense contracts, and nuclear research. It is not going to veterans’ benefits or health programs. Nor it is going to medical weapons or nuclear radiation injuries. This responsibility to armed service people will be passed along to civilian hospitals as part of their “staff challenge.”

Mounting Opposition

CMCHS has not slipped by unnoticed as hospital administrators and the Pentagon had hoped. Initially the plan unfolded smoothly with endorsements from the power centers of the medical industry. The American Hospital Association was willing “to cooperate with the DOD in the implementation of the system with our member hospitals.” The Joint Committee on Accreditation of Hospitals supported the plan and the American Medical Association pledged to “utilize its leadership position to commend the DOD program to the consideration of other components of the U.S. health care community.” However, as news of the plan has become public opposition has steadily gained momentum and encompassed increasingly broader sectors of the San Francisco Bay Area community, where the Pentagon first introduced the plan. An overview of opposition to the plan there could serve as a model for other areas.

In February 1981 the DOD invited hospital administrators of the Bay Area to a multimedia presentation introducing CMCHS, the latest in war preparedness for the medical community. They neglected to invite those most affected by the plan — hospital workers and patient communities. Word of this meeting slipped out and resulted in the first public awareness of CMCHS.

Shortly thereafter an ad hoc committee in opposition to the plan was formed. CMCHS exacerbated tensions which already existed between the medically underserved minority communities and the hospitals which supposedly care for them. In San Francisco and Oakland, members of community groups became involved in the fight against CMCHS. They were joined by activists in health workers’ unions; several locals of Service Employees International Unon (SEIU) and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) passed resolutions opposing the plan.

The campaign at San Francisco General Hospital was won through such a broad-based coalition. Opposition involved Latino community groups, black trade unionists, the Grey Panthers, other unions such as AFSCME local 1650, the San Francisco Interns and Residents Association, and El Salvador support groups. A rally of almost 100 people outside the hospital, and rising media attention, forced the hospital administrator who was on the verge of signing the Memorandum of Understanding, to back down.

In addition to San Francisco General, the most significant opposition locally has been mounted at public hospitals. Our experience as health care workers has led us to recognize several reasons for this.

At Highland, the Alameda County public hospital, sharp opposition to CMCHS at a meeting of the community advisory board, for example, resulted in a vote against endorsing the plan. Health workers and community members successfully debunked the slide show and patriotic pep talk given by Captain Hodge, the local DOD sales rep for CMCHS. As one member of the board said, “Whatever our personal views, we are here to represent the community.”

Contra Costa County Hospital went on record in early September as the first hospital in the country to formally oppose the plan. In a letter to the Pentagon, medical staff president Dr. Kathryn Bennet stated, ”the medical staff… does not wish to participate in CMCHS. The plan encourages preparations for a war of catastrophic proportions.” The letter placed the plan in the context of current social service cutbacks and concluded that “participation in CMCHS would offer tacit approval for the planning of a nuclear war.”

Another publicly funded system is the statewide University of California, which operates three large teaching hospitals. Due to public protest, they decided not to join the plan. Stanford University, faced with opposition from its medical staff, voted not to join CMCHS.

While public hospitals were encountering vocal protests, administrators of private hospitals were eagerly signing the M.O.U., sometimes with a poll of their medical staff, sometimes in total secrecy from all employees. Yet the success of public protests has had reverberations in the more insulated private sector. One Berkeley hospital administrator stated he would not sign because he expected “trouble from the community.”

The ABCs of Fighting HMOsAs the accompanying article suggests, fighting a hospital administration on behalf of consumers of their services presents a real organizing challenge. Public hospitals can be held accountable by the public bodies which administer them; private hospitals can be threatened with a consumer boycott. But what about Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) — the cradle-to-grave health care systems run on the basis of prepaid (usually payroll deduction) fees? On the West Coast there are several such HMOs, but the giant of them all is Kaiser Foundation Hospitals. The fight against Kaiser acceptance of the CMCHS plan is continuing as this article goes to the press; what follows is a summary of what we’ve learned about organizing against HMO cooperation with the Pentagon. Questions to Ask

Actions to Consider

— Coalition Against the Pentagon-Kaiser Agreement

|

Riding on the momentum of the various actions against CMCHS, other voices began rising in protest. Among these are the Catholic Church and Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR). PSR, a national organization of doctors opposed to nuclear war, began the first attempt to regionalize opposition. The organization’s opposition to CMCHS is based on their fear that the Pentagon plans a tactical nuclear war that could lead to an all-out nuclear exchange. PSR addresses itself to doctors and makes minimal attempts to educate and organize other parts of the hospital workforce. A letter from PSR to Chiefs of Staff at eligible Bay Area hospitals urged them to bring the matter before their medical staffs. Following this, 90 physicians at Kaiser-Permanente Hospital in San Francisco signed a resolution against Kaiser’s participation (see box). One weakness of PSR’s approach is that they limit their CMCHS opposition to the premise that it envisions a nuclear war. They do not take a stand against war per se, which implies silent complicity on conventional war scenarios such as the growing danger of U.S. intervention in Central America.

Appealing to another constituency, Roman Catholic Archbishop John Quinn addressed a San Francisco congregation of 2400 in mid-October, calling for a spiritual and secular program opposing nuclear proliferation. He specifically urged the administration and staffs of Catholic Hospitals to oppose CMCHS. The church makes it clear that they view this as a moral issue. On the heels of this widely acclaimed pastoral address, at least one Catholic Hospital in this area backed-down from participation in the plan.

Challenging Militarism

CMCHS, like the rise of militarism itself, is spreading across the country. Opposition is difficult to centralize, partly due to the large number of hospitals approached, and partly due to the lack of a unified movement opposing current U.S. policy and practice.

At this writing it has been about a year since the DOD came to town with their offer of a “gentlemen’s agreement” to hospital administrators. In that time thousands of people in the Bay Area have been alerted to the plan’s existence by speeches, articles, media coverage, petition campaigns and public actions.

CMCHS is a vital issue to raise in the context of today’s political and economic crisis. Stopping CMCHS will take a nation-wide broad-based movement opposing U.S. war preparations. Fighting CMCHS is a good way to expose the link between the military budget and the human service cutbacks that result from it. It is one more insidious piece of a jigsaw puzzle that attempts to make the unthinkable appear routine.

Not to WorryWe can rest assured, declares the Department of Defense in a late-March issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, that the Civilian-Military Contingency Hospital System (CMCHS) is based solely on a conventional warfare scenario, not a nuclear attack. In the same issue of the Journal, the Physicians for Social Responsibility decry the Pentagon’s plan as a diversion from the dangerous “potential for nuclear war.” No doubt the military is finding their plans for nuclear war hard to sell, deciding instead to peddle CMCHS as that garden variety conventional war we have come to know and accept. |

The authors are interested in hearing from people concerned about CMCHS, particularly those wishing to challenge CMCHS in their community. They have packets of material available, including the DOD plan, for $4.00. Please write: CMCHS, c/o Alameda County Labor/Community Coalition. P.O. Box 27163, Oakland, CA 94602.

>> Back to Vol. 14, No. 3 <<

- Department of Defense manual on the CMCHS plan: “CMCHS — In Combat, In the Community, Saving Lives… Together,” Foreword.

- Department of Defense, p. 1.

- David Allen, Hindsight, September 1981.

- Los Angeles Times, April 10, 1981.

- The “Vietnam Syndrome” is that polite term which refers to government fears that new U.S. military interventions abroad will lead to the renewal of mass political opposition at home.

- Department of Defense, p. 1.

- Department of Defense, p. 9.

- Department of Defense, p. 9.

- Department of Defense, p. 3.

- Department of Defense, p. 7.

- Department of Defense, p. 7.