This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Solitary Science vs. Connected Collectivism: Women, Work, & the Scientific Enterprise

by Leanna Standish

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 14, No. 5 September-October 1982, p. 12 — 18

Leanna Standish is beginning the first attempt at forming a women in science collective at Smith College. She is working on research on epilepsy and the brain.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Helen S. Brown and Judith Poole for editorial help.

For the last eleven years of my life I have been working as a physiological psychologist. During those years I have often felt a deep sense of failure, disappointment and vague anger. Until recently I believed that my personal difficulties as a scientist were unique to me—that my sense of failure to contribute to the scientific enterprise had to do with some tragic personal flaws. It never occurred to me that my experience of scientific institutions and of myself as a scientist might be gender-related. I have since learned that other women working in science have similar psychological experiences. Our common experience can be better understood through the psychological and sociological analyses of contemporary feminist thinkers such as Nancy Chodorow, Evelyn Fox Keller, Jane Flax, and Dorothy Dinnerstein. Feminist theory and my experience as a woman scientist forces me to ask: How can women scientists influence the future of our culture? Should we, or can we, alter the masculine orientation of scientific enterprise? How can women living and working in the last decades of the twentieth century think, experiment and make changes of cultural significance?

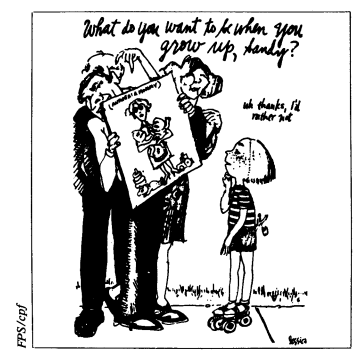

For the first time in history more than a few women are entering the sciences as students, many continuing on as scientists, professors, and physicians. Much of this change is a post-war phenomenon. At the end of the second world war, an optimism swept the nation; a national sense that anything was possible. The middle class men and women who parented my generation believed that their children could have and be anything if they simply worked hard enough. In the late 1940s and 1950s, though sex-role stereotyping was in its heyday, girls as well as boys received the powerful message of limitless individual possibility. Education seemed the means to all ends. For many of us, college was the inevitable consequence of high school graduation. Our intellectual potential was valued; occasionally we, as well as our brothers, received chemistry sets as holiday gifts. We read Nancy Drew and Landmark books about Madame Curie and Florence Nightingale. A tomboyish exploratory spirit was amusedly tolerated and sometimes even encouraged.

As young women we entered the university, some finding ourselves in small elitist colleges for women, and in this rarified environment we began to take ourselves seriously as thinkers and doers. We knew early on that college was just the beginning. There would be graduate school, medical school, law or business school afterwards. We had only vague notions of ourselves as successful women professionals, of self-actualization, power, and commitment to a purpose larger than ourselves. There were few models by which we could verify our nebulous fantasies. But as members of the new “liberated” generation, we saw ourselves as masters of our own scientific destinies. The abundance of male models seemed adequate enough. It never occurred to most of us to think that our gender, our femaleness, could or would stand in our way. This blindness, this denial of our difference, helped to save us from the immediate alienation and failure so many of our fellow women students experienced. Sex discrimination in the university seemed only to be a childish relic of the past. It seemed then that only we ourselves and our private inadequacies could prevent us from assuming important positions in the adult world of creative and deeply satisfying work.

Some of us were accepted for the small number of medical or graduate school slots allotted to women. Some of us managed four or six years ending in a degree and entrance into a professional career, but most of us did not. I have known many women who left graduate or medical school with feelings of vague alienation, in fear of facing competence exams, or in despair over the so-called writing block. I have known women, who after years of daily viscera-gnawing anxiety, mumble that they are still working on their dissertations.

A few of us stayed in school, though; we somehow received the necessary intellectual and emotional support. Perhaps there was a paternal male advisor, a rare female mentor, or other female students who formed what later came to be called support groups. Or perhaps the magic thing that happens so often to our male counterparts happened to us: we became captivated by the very subject matter before us. Our fascination with our work carried us through long periods when few around us seemed to care about what we were doing. Those of us who completed the process appended initials to our names and prepared to claim our share of grants, fellowships, faculty positions, administrative power, and journal, laboratory, and office space. It seemed that influencing the course of science and claiming our place in the policy-making hierarchy depended only on our hard work and our ill-conceived notion of self-discipline.

To strive to do valuable work as a female scientist is to strive for access to a part of society that embodies the quintessential values of patriarchal culture. The very word science implies masculinity.

Now, however, many of us face the tortuous realization that we are having little impact on the world. We fear our commitment to a higher purpose is waning, and we find it harder and harder to take ourselves seriously as thinkers. We notice that our male colleagues also fail to take us seriously. We blame ourselves and our secret tragic flaws. What has happened to our energy and sense of purpose? Our answers are often full of self-blame: things would be different if I worked harder; if I had more technical training; if I learned to program computers or design electronic circuits; if I wrote more fluently or read and thought more quickly; if I were more assertive, decisive, or articulate. We daily experience a sense of failure and alienation.

We must understand that we are struggling among men—in a centuries-old social environment created by men. As one ascends the scientific hierarchy one sees fewer women and more men. At the undergraduate women’s college where I teach, only 38 percent of the faculty are women, many of whom are untenured. At the prestigious biomedical research institute where I spent a postdoctoral year, only two of the fifty research faculty members were women, and they were married to two of the most influential male faculty members.

To strive to do valuable work as a female scientist is to strive for access to a part of society that embodies the quintessential values of patriarchal culture. The very word science implies masculinity. For many men, a central goal of creative enterprise is self-sufficiency. The male scientist tacitly accepts that to do good science one must do it alone. He favors isolation from colleagues working on problems similar to his own and from assistants working for him, not with him. Although goal-oriented male bonding sometimes makes projects work and new solutions merge, the predominant image of the scientist is as a solitary creator with a competitive spirit that pervades his feelings about his peers, both across the hall and across the country.

Recent feminists theory holds that the female psyche, as it is formed by the patriarchal social structure, is poorly suited to the solitary study of nature. Feminist writers in the fields of sociology (Chodorow), psychology (Dinnerstein), political theory (Flax), and philosophy of science (Keller) have argued persuasively that the personality structures of men and women have been fundamentally different since the beginning of organized patriarchal society.1 2 3 4Nancy Chodorow, perhaps more fully than any other writer, has outlined a theory of the origins of differences in female and male psychological development and the consequences of these differences.

Selves-in-Connection Versus Selves-in-Separation

Chodorow begins by stating that our first and primary caretaker during infancy and early childhood is, across history and across cultures, a woman. She claims that this fact alone has enormous consequences for the psychological development of female and male human beings. That our mothers were women means that for both male and female infants our first and most important social relationship is with a female member of the species. Our earliest feelings, thoughts, and actions all occur within the context of this first relationship with a female. We experience our first emotions, ranging from intense joy to terror and despair in the presence of and at the hands of a woman.

Briefly summarized, Chodorow’s thesis is that psychological development within the context of female-dominated infancy is different for male and female offspring. For males, successful emergence of an autonomous male self requires an unconscious and conscious denial of identity with this first relationship. She concludes, as does Dinnerstein, that the process of separation and individuation for the male infant and child requires a denial of dependence, intimacy, deep emotional connection with others. Males emerge as “selves-in-separation”, seeking psychological wholeness in autonomy, independence, solitary endeavor and competition. Being masculine entails denying everything that is female, including that part of himself that evolved in relation to his female primary caretaker.

Chodorow argues that the psychological development of the female infant is different from the male in both process and outcome because of her first intimate relationship is with a member of her own gender. The development of self-identity and individuation does not require a girl to disavow identity with her female caretaker. She need not deny her essential connectedness and complex inter-dependence with others. Female gender identity does not necessitate denial of the first relationship or the first self. As a result, female children emerge into maturity as “selves-in-connection” with a fundamentally different sense of self and relationship to others (and perhaps nature as well) compared to their male peers.

Jane Flax argues that the different developmental processes of men and women result in distinctly different psychological orientations. For males, as selves-in-separation, the development of deep and satisfactory intimate relationships is often difficult and painful, and in many cases simply avoided. For women, as selves-in-connection, the very meaning of life revolves around intimacy. Maintaining autonomy and independence outside of human intimacy may be a continuing and painful issue throughout adult life, more so now perhaps as social change urges her to enter into the patriarchal public sphere of work. The problem of life, simply put, is the on-going struggle to balance effectively our strivings for autonomy and self -identity and our longing for intimate, nuturing and complex connections with others.

Such feminist psychological analyses, of course, fail to consider at length important political and economic matters described in socialist feminist theory. Moreover, such analyses may further polarize men and women, say their critics, since they may be used to justify limiting the options available to women. Nevertheless, Chodorow’s theory especially provides a conceptual framework with which women can make sense of their experience as scientific workers. Besides offering a psychological explanation for sex-role differences that are common, if unspoken, knowledge, Chodorow tells us what we must do to eliminate these differences: we must insist on fully equal sharing of child-rearing responsibilities by both male and female parents.

Implications of Chodorow’s Theory for Science

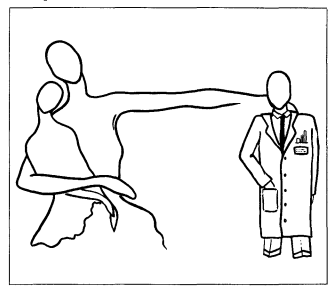

Women who devote themselves to science struggle in an environment poorly structured to meet their intellectual and emotional needs. The scientific workplace was designed for and by selves-in-separation. For women, work and human connection cannot be easily or happily separated. Chodorow’s analysis implies that men, as a general gender category, do not find working with women as intellectual and decision-making equals an easy task. Dinnerstein has even suggested that a too-close encounter with a true women peer and co-worker may undermine his sense of individuated power and autonomy. She has the seemingly magic power to know him deeply and force him to re-experience that dependent, engulfed aspect of self he knew in infancy when merged with his first and essential caretaker. Although such notions are difficult to verify, it seems clear that the male world of science and technology is not conducive to the intellectual, emotional or instrumental development of women. We must not be afraid to say that we are psychologically starving here.

Expecting ourselves to thrive while working alone, thinking alone and creating alone, we instead experience a disturbing immobilization, lack of personal power, and a fading sense of mission. Soon we lose the energy required to actualize our ideas or lift projects off the ground, and we search for an explanation for our feelings of defeat. Yet there seems to be no tangible impediment to accomplishment. The barriers are too long-standing, too deeply internalized and omnipresent to be perceived. This is why feminist theory is so important; it helps us to recognize the nameless, ubiquitous nature of the patriarchal world. As Simone de Beauvoir noted, to begin to see men and their world as “the other” is the first step in the development of a feminist consciousness. To admit that one is floundering in a work environment established long ago by and for men is not dishonorable; it is the natural outcome of our capacity for relational knowledge of ourselves, others and nature itself as well as our empathy, fluid interpersonal connectedness, contextual awareness and the blurring of the distinction between object and subject.

But I grow worried as I see more and more young women, especially feminists, reject science as a foreign and inhospitable world; as something that threatens the survival of the planet. It is true that thousands of women have found the professional world of men and their mixed-sex staffs dull and empty, lacking in vitality and creative energy that derives from true collective endeavor. However, it seems hasty and unwise to walk away from the entire scientific enterprise while pointing to the many formidable social and biological problems created by that enterprise. The science created by men has accomplished much that is powerful, transformative and, sometimes, even beautiful. Science has altered our existence irrevocably, and it will continue to do so at an ever greater pace. Science has been too successful to be stopped, even if we wished to stop it. Now more than ever, women must take active responsibility for directing the course of science and managing its deleterious consequences.

Strategies of Women Workers

Can women thrive—or even survive—within patriarchal science? Can we accomplish anything of significance in an enterprise that often seems devoid of genuine intellectual excitement and comraderie, its talk and journals filled with disconnected trivialities?

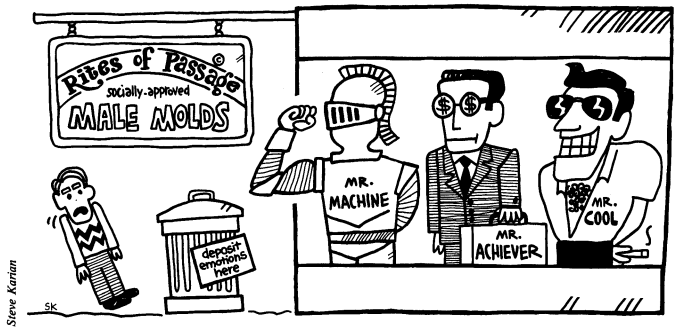

I have observed five general strategies that women in science and other professions have pursued, consciously or not, toward their goal of working productively in the public sphere. Briefly, these five strategies are: (1) becoming an invaluable support worker in a male-dominated enterprise, (2) becoming a “supermale,” (3) marrying one’s mentor, (4) choosing to work in “animate” science rather than “inanimate” science, and (5) forming a science work collective. Although I believe that the formation of women’s science collectives may provide the only suitable environment for the creative synthesis of feminisim and science, the prices paid in choosing other more conventional strategies need to be described.

The Invaluable Support Worker

The first strategy is the most common: the majority of women workers play support roles within a male-dominated enterprise. Within nearly every organization we find the irreplaceable female secretary, technician, administrative assistant, bookkeeper, or research or teaching assistant. She is the person who makes it all work, who makes certain that her male boss keeps his professional agreements, looks presentable to the public, and feels good about himself. She provides the empathy and thoughtful nurturance that, even the men will admit, makes their organization work. Such a woman often has no special academic credentials, and usually she is not well paid. She may consider her work meaningful, however, for it brings her feelings of collective accomplishment and personal worth.

Although the laboratory technician or executive secretary may feel that she plays an important role in making ideas into reality, the problem is that the ideas are nearly always men’s. Men’s ideas, of course, are affected by a female-dominated infancy and the values of the self-in-separation, which has denied and repressed the capacity to know intimately other human beings and nature. A woman doing support work rarely has genuine decision-making power. Her power, if she has any derives from her role as executor of men’s plans; she is not truly participating in history making. Knowing that much of male-dominated enterprise is ill conceived, empty of real human meaning, and sometimes even dangerous to the survival of our species, the woman who freely chooses such a role fails to take responsibility for the future. Being an invaluable support worker means relinquishing one’s power to shape the future in exchange for the satisfaction of social integration within the patriarchal work place.

The “Super-Male”

In nearly every work place there is a woman whose thinking and action is more masculine than men themselves. She is more hard-nosed, more enamored with rigor and self-discipline, and more eager to uphold the rules and regulations of the patriarchal institution in which she is usually a token. She learned early how to play and win the power game within her profession.

We can only guess what psychological history might lie behind such adult behavior. Perhaps girls, like boys, sometimes seek escape from engulfing intimacy in infancy and childhood. Their struggle for isolation and mastery over people and things may lead them to deny their essential connection to others. They may find the social environment of patriarchal institutions a place to reaffirm their autonomy and escape the discomfort of intimate relationships. Such women, productive as they may be, are only perpetuating the values and hierarchical organization of patriarchal science and preventing the emergence of a feminized science.

The Wife of Her Mentor

Many successful women scientists now in their forties, fifties, or sixties married their male mentors, who were already established in the profession and usually older. Such a woman, when asked about her husband’s role in her career, will freely admit the importance of his support and intellectual involvement in her work, which often began as his work. Despite the setbacks from pregnancy, infant and child care, and often primary responsibility for maintaining a household, marriage to her mentor may have been a necessary step to success in the scientific world.

The more a woman’s goals and methods of inquiry derive from her husband and the patriarchal institutions in which his ideas developed, the less chance she has of helping to create a new kind of science—a science not directed at conquering and sometimes destroying nature. If it is true that our traditional child-rearing practices generate in men and women very different ways of perceiving and understanding other human beings and nature, then it follows that scientific inquiry might be very different, were women the originators and executors of their own scientific questions and ideas. We have no way of knowing how science and technology might be transformed were they directed by selves-in-connection rather than selves-in-separation, but the radical feminist vision tells us that women have the potential to perceive and understand in ways that are as yet unknown. It is unlikely that the old but still powerful notion of man as conqueror of nature—as isolated, dispassionate manipulator of his mechanistic world—would be so fundamental to scientific enterprise were science in the relational hands of women.

The “Soft” Scientist

One could reasonably conclude from Chodorow’s work that for fundamental psychological reasons inanimate science, the science of things, is less likely to fascinate women and attract their intellectual commitment than animate science. It is relatively easy for a woman, scientist or not, to become fascinated with problems of the human realm. When one tries to name prominent contemporary female scientists, the names Margaret Mead, Karen Horney, Anna Freud and Jane Goodall come to mind first. It is no accident that listing prominent women in psychology, anthropology, or sociology is far easier than listing those in elementary particle physics or radioastronomy, for the psychological orientation of most women is poorly suited to the study of small, invisible objects or large, distant ones, especially when several levels of machinery and computation mediate between the scientist and the phenomenon under study. Whereas, many thoughtful scientists have begun to understand that complete control over that which is studied, as well as objective separation of subject and object is neither logically nor, in practice, possible, the scientific establishment continues to teach that scientific understanding is equivalent to control. If the scientist can control all the variables affecting a phenomenon, he/she has succeeded, it is said, in understanding the phenomenon. The climate and paradigms of the hard sciences are alien to most women, while providing a comfortable home for selves-in-separation. It may be that the paradigms which generate fast paced scientific activity within these fields, because they derive from male psychology, are unable to captivate the woman who sees in the paradigm only half-truths.

Although we should celebrate the partial feminization of the “soft” sciences, it is with alarm that I watch women limiting themselves to these, especially now, as it becomes more and more apparent that serious human problems can result from swift technological advances in the male-dominated “hard” sciences.

Although we should celebrate the partial feminization of the “soft” sciences, it is with alarm that I watch women limiting themselves to these, especially now, as it becomes more and more apparent that serious human problems can result from swift technological advances in the male-dominated “hard” sciences. These are the most dangerous sciences; it is here that we need women the most.

The Science Collective

Attracting more women into the harder sciences will require more than affirmative action in national searches, “leniency” in tenure decisions, or a greater number of scholarships for women. As long as our child-rearing practices remain unchanged, and science is defined by men who have experienced a female-dominated infancy, women will need to construct their own scientific world and define their own scientific goals. The formation of women’s scientific collectives may be a viable solution until that time when both infancy and science are freed from the constraints of psychological genderization.

The women’s movement has given birth to a variety of women’s work collectives: art collectives, legal, music and therapy collectives. These organizations have been established within a feminist framework and exist to provide more humanized services to clients as well as a special work environment for its working members. Women writers, artists and musicians are creating their own publishing houses, galleries and production studios. Women’s collectives are transforming the very nature of the enterprise and purpose for which they were formed. Women’s music, art and human services seem qualitatively different from their traditional counterparts. Health care is holistically oriented, emphasizing prevention and personal responsibility for the functioning of one’s own body. Legal services are designed to inform others of their legal rights and to teach women to use and change the legal system, without victimization.

Women’s work collectives share in common an explicit recognition, even celebration, of women as selves-in-connection. They strive to generate a work environment that women need to be creative and productive. The collective process of decision-making is viewed as important as the decisions themselves. Power, work and responsibility are shared. The power hierarchy so characteristic of male organizations is opposed and often erased. The profit and competition motives are conspicuously absent. Collectives exist to provide human services and cultural beauty to people who cannot afford the arrogant prices of traditional, and often anti-female, legal, medical or psychological help. They derive from a fundamentally different psychological orientation. Working towards a set of goals for an interconnected and relational public sphere means cooperation, equal distribution of power and responsibility, and personal empowerment, not mastery, control, reductionism and competition.

Women collaborating as peers pay special attention to the details of their decision-making and executing process. In so doing, they have discovered better ways to get things done. The goals of the collective are under constant scrutiny; revised and finely modulated by an ever-changing world and by the consequences of their own work. The effects of the psychological milieu provided by the the collective on the well-being and productivity of each member is closely monitored and in the process we have discovered new ways for people to think and act together.

Many difficulties face each collective and economic survival is often in question. However, during the next decades the formation of women’s work collectives may be the best strategy for providing for oneself and other women a social environment in which women can truly work, can accomplish goals for the public sphere and take active responsibility for the course of social evolution. There is no area of human life needing more desperately the energy and wisdom of women than science and technology—the very symbols of masculine endeavor and, increasingly, that part of the culture having the greatest impact on every level of human existence.

Male scientific organizations require enormous amounts of federal, state and private financial support for their operation. Millions of dollars are needed to provide the technical engineering and instrumentation that lies at the foundation of the physical and natural sciences. Most male laboratories are composed of more than scientists; specialists in electronics, computers and mechanical engineering are necessary. The scientific enterprise is unequalled in its dependence on coordinated individual effort. Yet cooperation and collectivism of ideas and material resources are rarely apparent. To women, especially feminists, it is an alien world which contradicts, ignores or ridicules the female self-identity and mode of being.

The electronics engineer may be vital to the sucess of a project, but rarely is he/she involved in the evolution of the ideas and theories from which the project originates. He/she may be ignorant of the scientific field or conceptual focus of the experiments for which he/she builds his/her circuits. The computer programmer may be concerned only with the writing of the most efficient program to execute a task designated by the “chief” of the laboratory. The technician may analyze tissue samples, but be ignorant or disinterested in the questions being asked of that tissue. This is seen by many well-established scientists as the way to do science. The more personnel under one, the more federal money financing the work, the more successful he/she seems. It has even been argued that the coordination of data produced by psychologically and intellectually separate individuals guarantees “blind” objectivity.

The formation of a women’s science collective might be one of the most exciting and important of social experiments. Such a strategy may give rise to new questions, new paradigms, new ways of knowing and the chance to explore the meaning of feminist science. However, even if we could conceive of collectivized science created out of a feminist vision, the technical and economic obstacles are great. Neither the creation nor the survival of other forms of women’s work collectives have been so critically linked to technology and large scale economic support. Mobilized social and economic support from feminists and the scientific community will be necessary for such a social experiment to succeed.

While some of the products and consequences of science threaten our very existence, we cannot forget that science has proven itself to be one of the finest paths to deeper human understanding, to the extension of our perceptual experience across time and space, and to the enrichment of the quality of our lives. Such a powerful tool is too useful and too powerful to be left solely in the hands of female-raised males. Neither should we, as women, deny our special relational capacities in order to do science. We must find new ways to preserve and utilize ourselves while working toward the expansion of scientific knowledge and responsible control of technology. We can no longer be satisfied with merely a support role nor a life of quiet desperation within male enterprise. During the last decades of this century we must take it upon ourselves to try to create women’s science collectives.

>> Back to Vol. 14, No. 5 <<

REFERENCES

- 1. Chodorow, Nancy The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Dinnerstein, Dorothy The Mermaid and the Minotaur: Sexual Arrangements and Human Malaise. New York: Harper and Row, 1977.

- Flax, Jane “The conflict between nurturance and autonomy in mother-daughter relationships and within feminism.” Feminist Studies, vol. 4, 1978, pp. 171-189.

- Keller, Evelyn Fox “Gender and science.” Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Science, vol. 1, 1978, pp. 409-433.