This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

“Selling the Tree of Knowledge”: Academia Incorporated

by David Noble

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 15, No. 1 January-February 1983, p. 7-11 & 50-52

David Noble teaches in the Science, Technology, and Society Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has been writing extensively on the relationship between academic research and military/corporate funding. He is the author of America By Design.

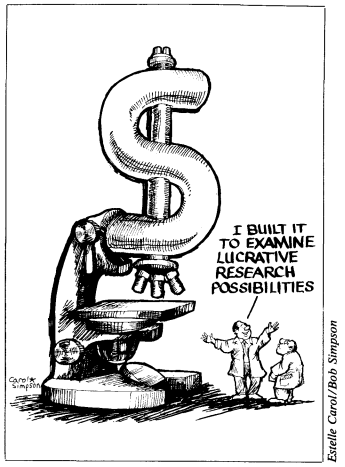

American universities, public and private alike, are invaluable resources. Supported primarily at public expense, in the interest of society as a whole, they serve as vehicles for the transmission of society’s store of knowledge and skills, dominant ideas and values. They function as an independent space within which to reflect critically on society. They are also the major agencies dedicated to the advancement of scientific knowledge in this country. Today, as never before, this vital public resource is being transformed into a private preserve. Private corporations are purchasing privileged access to universities in order to gain control over the research carried out there. Scientists and administrators within the universities are fully cooperating by selling the public birthright to the highest bidder.

Upon close inspection, it becomes clear that both the buying and selling are being done by a relatively small elite corps of academics and industrialists who rotate routinely among positions in the interrelated corporate, scientific, and university arenas. It is also clear that their actions are in violation of both the public trust and the public interest, diverting taxpayer resources for private purposes at public expense. This “selling of the tree of knowledge to Wall Street,” as Congressperson Albert Gore, Jr. has termed it, has had the consequence of blurring the distinction between two quite different institutions: the university and the private industrial corporation.1 As a result, we see the corruption of neutral competence and the restriction of the academic freedom of independent and critical thought. Most importantly, this transformation constitutes a serious threat to the traditional American values of democracy and equality. Placing public resources in a few private hands denies access to those less endowed or less powerful taxpayers who must continue to shoulder the major cost for universities—the same taxpayers who will inevitably bear the consequences of the privately-directed research done in their name.

There are many reasons why this transformation is taking place now.2 The relative decline in government funding, a reflection of the recent conservative trend in American politics, has prompted university administrators to seek support from the private sector. Government demands for greater university accountability during the last decade has also driven university administrators into an alliance with private industry, and into a campaign against government regulations. In addition, new developments in high-technology areas such as telecommunications, computers, and microelectronics have established the importance of scientific “intellectual capital” in the latest round of intensifying international competition. This competition is based upon an obsession with innovation and technology transfer and has encouraged an “industrial connection” between science-based firms and research universities.

But the transformation of our universities can not be blamed solely on recent high-technology developments. It is the natural consequence of postwar patterns of university-government relations, especially with respect to scientific research. Established nearly four decades ago, these patterns lend themselves perfectly to the commercial abuse of the nation’s scientific resources.

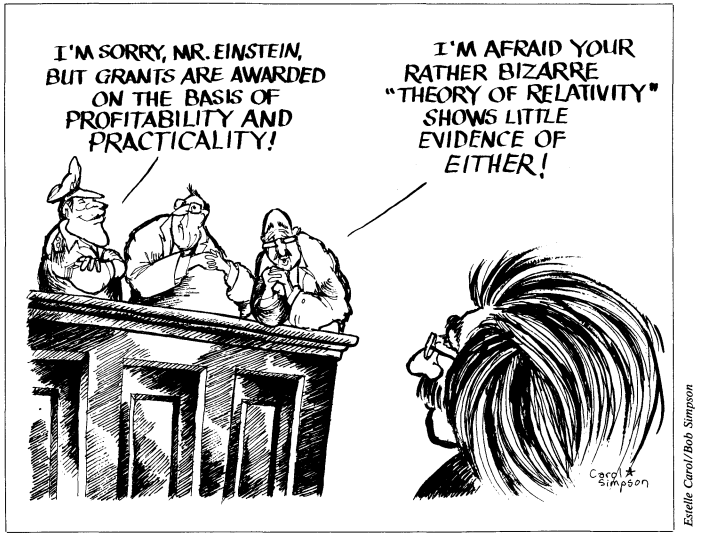

The current policies give unique license to private citizens—academic scientists in universities—to allocate and use public funds as they see fit, so long as it contributes to the interests of science as defined by scientists. This is a license to commercially exploit public resources for private gain. It is imperative to forestall the type of elite control of science which is now taking place on the nation’s campuses. To do this effectively, we must examine the history of the postwar patterns of research funding that we have come to accept as natural and routine.

The Origins of Postwar Funding Patterns

During World War II, the federal government became the major supporter of academic scientific research. Prompted by wartime expediency, the civilian-run Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) established the now-familiar pattern of government research contracting. In this relationship, private firms and universities began to perform the bulk of research and development work for the government. In return, the government financed their expanded operations. By the war’s end, there was widespread agreement among scientists and government officials alike that such federal support of university-based scientific research should continue. The academic scientific community was especially enthusiastic about the prospect of sustained public support for their work. As historian Michael Sherry has observed, the scientists “led the drive to institutionalize the war-born partnership with the military … [they] did not drift aimlessly into military research, nor were they duped into it. They espoused its virtues, lobbied hard for it, and rarely questioned it.”3

As early as 1941, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) President and OSRD leader Karl Compton noted that wartime research would “presage a new prosperity for science and engineering after the war.” Edward L. Bowles, MIT electrical engineer and science advisor to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, urged that a “continuing working partnership” be established after the war between scientists, educational institutions, and the military. This postwar integration, said Bowles, “must transcend being merely doctrine; it must become a state of mind, so firmly embedded in our souls as to become an invincible philosophy.” As Sherry comments, “Compton and other proponents of pure science saw the chance to turn a temporary windfall into permanent federal support … The more sophisticated propagandists of scientific preparedness … viewed weapons research as part of an integrated program of peacetime mobilization.”

During the war, the direction of research had been determined by military criteria. After the war, scientists had to face the problem of defining whose objectives and what criteria would set peacetime research priorities. How might scientific and technological efforts be encouraged under private auspices, at public expense, while still safeguarding the larger public interest and the standard of equity? How might the government guarantee the autonomy and integrity of science, yet uphold the principle of democratic control over and accountability for public expenditures? These challenging questions were never resolved during the early debates over postwar science policy; nor did scientists ever confront them seriously. The scientists’ characteristically contradictory positions served merely to allow them to have their cake and eat it too.

During the war, the direction of research had been determined by military criteria. After the war, scientists had to face the problem of defining whose objectives and what criteria would set peacetime research priorities.

“Trickle-Down” Science

Essentially, with regard to the public interest, scientists adhered to a “trickle-down” theory akin to the classical economics espoused by their friends in industry. They conveniently believed that if scientists remain free to pursue their calling as they see fit and to satisfy their curiosity about nature, their efforts will inevitably contribute to the general good. They believed that what is good for scientists is good for science, and what is good for science is good for society and they argued this position as a mere article of faith.

Their faith in science was almost religious. At the core of their belief lay the myth of an autonomous science, destined by Fate to be always in the public interest. It followed from this view that any undue government intervention in science, in the name of democracy, would have the same unwanted effect as would, say, undue government interference in the supposedly self-regulating market: it would upset the delicate mechanisms of progress and do irreparable damage to society. In short, scientists claimed unique privileges for themselves, their community, and their institutions-to be publicly supported in their activities but to be otherwise immune from public involvement.

Predictably, then, when the scientific statesmen sought to perpetuate the pattern of military contracting established by the OSRD during the war, they attempted to do so without legislation and without having to go through Congress.

The Academy Plan

The idea for a research board funded by the military but administered by civilian scientists was first advocated by Frank Jewett, former head of Bell Laboratories, Vice President of American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T), and president of the National Academy of Sciences. He suggested that the board be administered through the private National Academy and promoted by a War Department Committee on Postwar Research, which was headed by General Electric president Charles E. Wilson. The “Academy Plan,” as it became known, reflected the scientists’ double desire for funds and autonomy, as well as their deep distrust of the legislative processes of democracy. As historian Daniel Kevles has noted, the members of the War Department Committee on Postwar Research “believed that scientists, at least academic scientists, did not require subjection to normal democratic controls,” a belief that reflected their “politically conservative propensities” and especially “their tendency to be comfortable with the entrustment of public responsibility to private hands.”

The plan outlined by Jewett met with a certain amount of criticism in the Senate. However, since the National Academy of Sciences had already been chartered by Congress, the Academy Plan could be implemented by Executive order alone, bypassing the Senate. This would enable the scientists to avoid having to deal with the Senate’s opposition, an evasion which the promoters of the Academy Plan considered to be its chief advantage. In late 1944, a “Research Board for National Security” was established along the lines of the Academy Plan with the expectation that it would eventually be funded through military appropriations. At a gala inauguration dinner in March 1945, the elite of the scientific and military worlds, anticipating executive approval, congratulated one another on their devotion to peacetime progress through military strength. Their celebration, however, was short-lived.

Barely a month later, President Roosevelt killed the Board by forbidding any transfer of funds to it from military appropriations. The sponsor of this executive action was Budget Bureau Director Harold Smith. Smith had become concerned about the scientists’ attempt to circumvent the legislature and insulate themselves from government supervision. He viewed the entire plan as fundamentally undemocratic. Specifically, he rejected “the assumption that researchers are as temperamental as a bunch of musicians, and that consequently we must violate most of the tenets of democracy and good organization to adjust for their lack of emotional balance … The real difficulty,” Smith opined, was that the scientists “do not know even the first thing about the basic philosophy of democracy.” The New Republic agreed. Referring to the “fantastic suggestion that in the long run the National Academy of Sciences should usurp the functions of the Executive,” the journal argued that “the American people should no more acquiesce in the present scheme than to a proposal that the carpenter’s union [alone] should elect members of a board which is to plan public works.”

The demise of the Research Board for National Security meant that the National Academy of Sciences would not serve as the conduit for military funding of civilian research. This did not put an end, however, to the scientists’ dream of military support for their activities. Congress soon authorized military agencies to award research contracts directly to the universitites, providing a more significant and enduring vehicle for defense-funded research.

Military Control of Research

The Navy was the first to assume responsibility for support of academic research. Admiral Furer, Navy coordinator for research and development, had formulated elaborate plans for Navy support of science. This prepared the Navy to take advantage of the congressional authorization of funds. Shortly thereafter the Office of Naval Research (ONR) was established to contract with universities for military-related research. Within a few years the ONR had established itself as, in Kevles’ words, “the greatest peacetime cooperative undertaking in history between the academic world and the government.”

By 1949, the ONR was sponsoring 1200 research projects at 200 universities, involving 3000 scientists and nearly as many graduate students. Equally important, the ONR contract system was patterned after that established by the OSRD, which guaranteed scientists a considerable degree of autonomy. Daniel Greenberg observed that the Navy subsidized science “on terms that conceded all to the scientists’ traditional insistence upon freedom and independence—thereby institutionalizing in peacetime the concept of science run by scientists at public expense.” In 1949 the Air Force joined the Navy as a major supporter of university-based research, along similar lines. By 1948, the Department of Defense research activities accounted for 62% of all federal research and development expenditures, including 60% of federal grants to universities for research outside of agriculture. By 1960, that figure had risen to 80%. Thus, the scientific elite were successful in their effort to secure military support for postwar science, in the name of national security.

Funding Civilian Research

The scientific elite also sought to create a permanent federal agency which would foster a broader range of civilian research activities, in the name of economic innovation. A leader in this effort was Vannevar Bush, who headed the OSRD during the war and who was a former Dean of Engineering at MIT, a major military research center. Bush was a cofounder of Raytheon Co., a major defense contractor, and he pioneered development of analog computers for ballistics calculations. He was also a director of such profit-oriented science-based firms as AT&T and Merck & Co. He was thus no stranger to—nor critic of—military preemption of science. Yet, when it came to democratic scrutiny or control of science by Congress, Bush posed as a champion of so-called pure science. “The researcher,” he insisted, is “exploring the unknown,” and therefore “cannot be subject to strict controls.”

The effort of Senator Harley Kilgore of West Virginia to democratize science prompted Bush to formulate specific plans based on scientists’ interests. In short, what Vannevar Bush and his colleagues were responding to was a threat that the Academy Plan promoters had hoped they could circumvent—the threat of greater democratic control over postwar science.

The Push For Democratic Control

Senator Kilgore, chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on War Mobilization, advocated tight federal controls over government science spending and public ownership of patents resulting from publically-supported research. He also favored a policy stating that scientists must share control over science with other interested parties. Scientists, argued Kilgore, must be responsive to normal democratic controls like everyone else. Scientific research should be directed less by the mere curiosity of scientists than by an awareness of pressing social needs.

During World War II, large firms and the major private universities received the lion’s share of defense contracts, at the expense of smaller firms and less-favored universities. Of all wartime research and development contracts, two-thirds went to 68 firms, of which 40% went to only 10 firms. Of the $250 million in contracts given to 200 universities, two-thirds went to 19 favored schools; the largest portion, $56 million (or roughly one-fifth of the total budget) went to MIT. Early in the war, Kilgore had formulated a bill for a new Office of Science and Technology Mobilization. His immediate concern was to utilize more fully the nation’s scientific resources for the war effort, through a more equitable distribution of federal support than that being provided by the OSRD. Kilgore was very much concerned that public resources like science be protected from private control by the “monopolies.”

In addition to the issue of distributing funds more equitably, Kilgore was concerned with patent ownership. At the discretion of OSRD leadership, over 90% of the research contracts awarded during the war granted ownership to private contractors of patents on inventions resulting from publicly-supported research. Kilgore considered this policy to be an unwarranted giveaway of public resources. He did not consider corporate control of the fruits of research to be in the best interest of the American people. Although patents were granted to companies as an incentive, to encourage them to develop their ideas and bring new products and processes into use, Kilgore knew that such a policy sometimes had the opposite effect. Patent ownership could also lead to the restriction of innovation, in the interest of corporate gain.

Above all, Kilgore was determined to have the government insure that science be advanced according to the time-honored principles of equity and democracy. Assistant Attorney General Thurman Arnold joined Kilgore in his efforts, declaring that “only government could break the corner on research and experimentation enjoyed by private groups.”

Thus, Kilgore sought to alter the patterns of research established during the war by the OSRD. His proposed Office of Science and Technology Mobilization, which evolved into a plan for a postwar National Science Foundation, emphasized lay control over science as well as a fair measure of political accountability. It was to be headed by a presidentially-appointed director to guarantee greater accountability. The director would be advised by a board composed of cabinet heads and private citizens, insuring the representation of consumers, small business, and labor, as well as of the scientific establishment and big business. Moreover, the proposed agency would strive to grant contracts on an equitable basis to firms and universities, and would retain ownership of all patents as a safeguard of the public interest. Kilgore insisted that the agency be viewed as a means of meeting social ends, not merely as a vehicle for “building up theoretical science, just to build it up.”

The Establishment Fights Back

Vannevar Bush was alarmed by Kilgore’s proposal for a scientific organization explicitly responsive to the interests of nonscientists. He was joined in his opposition by his colleagues in the Army, the Navy, the National Association of Manufacturers, and the National Academy of Sciences. Frank Jewett viewed the Kilgore plan as a scheme for making scientists into “intellectual slaves of the state.” Harvard president and fellow OSRD leader James Conant warned of the dangers of Kilgore’s “dictatorial peacetime scientific general staff.” Such strident calls for scientific liberty appeared compelling but, as these men well knew, science had never been truly independent. Whether directed toward industrial or military ends—as in Jewett’s Bell Laboratories or Conant’s Manhattan Project—science had always followed the course set for it by political, industrial, or military priorities, either through general patterns of funding or detailed management supervision. The issue here was not control of science, but control by whom—by the people, through their democratic processes of government, or by the self-chosen elite of the military-industrial-education complex.

Bush, whose own technical career centered upon the solution of problems for the utilities and the emergent electronics industries, assailed Kilgore’s emphasis upon the practical, socially useful ends of scientific activity. Posing once again as a champion of “pure science,” he derided the Kilgore agency as a “gadgeteer’s paradise.” He also strongly opposed Kilgore’s insistence upon lay control of science, arguing that this would violate the standard of excellence which supposedly marked scientists’ control over science.

In response to Kilgore’s challenge, Bush and his colleagues formulated a counter-proposal for a National Research Foundation (later called a National Science Foundation). Bush proposed the establishment of a board-run agency, buffered from presidential accountability and most likely to serve as a tool of the academic scientific community which Bush represented. He also argued for a continuation of the OSRD patent policy. This policy gave the director of the agency discretion in awarding patent ownership to contractors. Central to the Bush plan was professional rather than lay control over science. Bush outlined his plan in the famous report “Science, the Endless Frontier.” Not everyone was convinced. According to science writer Daniel Greenberg, the plan “set forth an administrative formula that, in effect, constituted a design for support without control, for bestowing upon science a unique and privileged place in the public process-in sum, for science governed by scientists and paid for by the public.” Bush acknowledged that he was asking for unusual privileges for his constituents but insisted that good science was an essential priority for a strong and prosperous society.

James R. Newman, top staff official of the War Mobilization and Reconversion Office argued that the Bush plan “did not fulfill the broad, democratic purpose which a Federal agency should accomplish.” Oregon Senator Wayne Morse insisted that the Bush scheme was being “fostered by monopolistic interests” and was opposed by “a great many educators and scientists associated with state-supported educational institutions.” Other outspoken opponents of the Bush proposal included White House aide Donald Kingsley and Clarence Dykstra, chancellor of the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA).

The issue here was not control of science, but control by whom—by the people, through their democratic processes of government, or by the self-chosen elite of the military-industrial-education complex.

Many politicians wearied of what they viewed as the self-righteous arrogance of the scientific elite. E. Maury Maverick, Director of the Smaller War Plants Corporation, testified at a Senate hearing on the postwar science foundation legislation. “I do not wish to impugn even remotely the patriotism of the great scientists who have already appeared before you,” Maverick replied to Isaiah Bowman, well-known scientist and President of Johns Hopkins University. “But I suggest that all scientists remember that there are other patriots in the world beside themselves and it would be a good idea to develop some social consciousness … The political character of our Government guarantees democracy and freedom, in which the people, through their government, decide what they want. A scientist, because he receives $50,000 a year working for a monopoly, or a big business, must remember that this does not necessarily make him pure except that he may be a pure scientist.”

Doing Business with AcademiaSome recent major contracts between corporations and universities and their affiliate institutions

*Engenics is a joint venture of Bendix, General Foods, Koppes, Mead, Noranda Mines, and Elf Aquitaine.

Reprinted with permission from the New York Times, October 17, 1982 |

The Birth of the National Science Foundation

The two bills for a postwar science foundation—Bush’s and Kilgore’s—were debated in Congress for several years after the war. During this time a Republican majority came to dominate both houses. The Kilgore version, endorsed by the Democratic administration, encountered stiff opposition on Capitol Hill. The Bush version passed through Congress in 1947, only to be vetoed by President Truman. Truman’s veto echoed Kilgore’s concerns. Truman commented: “This bill contains provisions which represent such a marked departure from sound principles for the administration of public affairs that I cannot give it my approval.” He concluded that the proposed National Science Foundation “would be divorced from control by the people to such an extent that [it] implies a distinct lack of faith in democratic processes. I cannot agree that our traditional democratic form of government is incapable of properly administering a program for encouraging scientific research and education.”

After the veto, the National Science Foundation (NSF) bill languished in Congress while the ONR continued to grant university researchers financial support. Finally, early in 1950, a compromise bill, which was in reality a triumph for the Bush approach, was passed by Congress. It was sustained by Truman, who was by then engulfed by the Cold War and the exigencies of “national security” once more. The 1950 bill conceded to Kilgore and Truman a presidentially-appointed director-to be advised by an exclusive board of private scientists. The first director, Alan Waterman, who was to head the NSF for a decade, had been chief scientist at the ONR. He was committed to continuing the patterns established during the war—science run by the scientist at public expense. “It is clearly the view of the members of the National Science Board,” the Fourth Annual NSF Report declared, “that neither the NSF nor any other agency of the government should attempt to direct the course of scientific development and that such an attempt would fail. Cultivation, not control, is the appropriate and feasible process here.”

The ONR and the NSF institutionalized the patterns of research funding and administration that had been created during the war. Henceforth, science would be “cultivated” at the taxpayer’s expense but with little public accountability. Taxpayers now had to be content that the advancement of science by scientists would inevitably meet their interests as well. In the Department of Defense and the NSF, and later in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Institutes of Health, this quasi-religious view of science came to predominate. Academic scientists and administrators were granted unusual license to conduct their government-supported affairs with little public oversight, with little regard for the larger social purposes of science, and with little more than polite contempt for the public interest.

The interests of scientists are not all scientific. In the postwar electronics boom of the 1950s and 1960s, many academic scientists routinely became corporate consultants, directors, officers in private companies, and even “spin-off” entrepreneurs in their own right. University faculty members thus divided their time between being stewards of publicly funded research centers and agents of commercial enterprise.4 Predictably, they became the focus of renewed criticism, but this time, the criticism lacked the coherence that it had once had and the critics lacked political power.

First Time Tragedy, Second Time Farce

More recently the connection between academia and industry has been reinforced. And, once again, criticism of the commercial connections and dealings of university-based scientists has reemerged. But this time, the critics may prove to be more effective. The California Rural Legal Assistance agency (CRLA), for example, has sued the University of California for using public funds to develop farm mechanization technology. This agricultural equipment serves the interests only of large growers, at the expense of small growers and farmworkers. The CRLA charges that this research was directed not by public-spirited scientists but by collaboration between university researchers and big agribusiness firms, with which the university is intimately linked. More recently, the CRLA has compiled extensive documentation of conflict of interest throughout the University of California system and has called for the State of California to apply state conflict-of-interest regulations to university personnel.

On the national level, Congressional hearings have been held by Congressperson Albert Gore to look into the new industrial invasion of the universities. The hearings will assess the undue leverage over public resources now being acquired by private firms. Throughout the country, critics are beginning to call for government measures to safeguard the public interest, and to insure that the public gets a fair return, in terms of jobs, revenues or well-being, from the firms which are permitted to exploit them. Most importantly, critics are beginning once again to envision a democratic mechanism that would oversee university-based research activities in order to render science and technology compatible with democracy and the public interest.

Critics are beginning once again to envision a democratic mechanism that would oversee university-based research activities in order to render science and technology compatible with democracy and the public interest.

Academic scientists with corporate connections are trying to protect private prerogatives by reviving the romantic contest between the forces of freedom and progress (science and universities) against the forces of tyranny and reaction (government). Poised as champions of untrammeled inquiry, they are boldly defending university scientists from government “interference” while diverting attention from their arrangements with private firms which readily permit similar “interference.” This corporate scientific campaign has recently taken shape in a new committee of the National Academy of Science. This committee is charged with the task of promoting cooperation in science and guarding against any and all restrictions on the flow of scientific information. The committee is composed equally of university administrators and executives of multinational corporations.

Thus, as in the early postwar years, the academic scientists have joined forces with their industrial counterparts to foster private interests in the name of science. They are not unaware of the history they are trying to recreate. Before the late Philip Handler left the presidency of the National Academy of Science (NAS), he set up a committee charged with the task of drafting an updated version of Vannevar Bush’s “Science, the Endless Frontier.”

“It appears to me,” said current NAS president Frank Press recently before the House of Representatives Science and Technology Committee, ”that we must once again reaffirm the credo so aptly outlined (in Bush’s 1945 report) … That the advancement of science is inevitably in the public interest.”5 Whether they will be able to pull this off a second time remains to be seen.

>> Back to Vol. 15, No. 1 <<

NOTES & REFERENCES

- Albert Gore, Jr., speech on university-industry relations, MIT, March, 1982.

- For a fuller account of recent developments, see David F. Noble and Nancy E. Pfund, “Business Goes Back to College,” The Nation, September 21, 1980; David F. Noble, “The Selling of the University,” The Nation, February 6, 1982; and David Dickson and David F. Noble, “By Force of Reason: The Politics of Science Policy,” in The Hidden Election, edited by Thomas Ferguson and Joel Rogers. (New York: Patheon), 1982.

- This history of the postwar period, and all quotes are based upon the following:

James P. Baxter, Scientists Against Time, Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1946.

Dan Greenberg, The Politics of Pure Science. New York: New American Library, 1971.

Daniel J. Kevles, “The National Science Foundation and the Debate over Postwar Research Policy.” Isis, vol. 68, 1977.

Daniel J. Kevles, “Scientists, the Military, and the Control of Postwar Defense Research.” Technology and Culture, vol. 16, 1975.

James L. Penick, et al., eds., The Politics of American Science, 1939 to the Present. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1965.

Michael D. Reagan, Science and the Federal Patron. NY: Oxford University Press, 1969.

Michael S. Sherry, Preparing for the Next War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

- Robert Linnell, Dollars and Scholars. New York: Carnegie Foundation, 1982.

- Frank Press, Testimony before the House Science and Technology Committee, Spring, 1981.