This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Lesbian Health Care: Issues and Literature

by Mary O’ Donnell

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 10, No. 3, May/June 1978, p. 8–19

Lesbians face great discrimination when seeking health care. Although this discrimination can be found in all health-related areas, it is probably most predominant in the areas of gynecology, reproduction and mental health. Most doctors view women in terms of reproduction and assume that all of us either use or need contraceptives. In most parts of the country, the only place a woman can get free gynecological care is in a birth control clinic. At the same time, the health profession does not recognize that lesbians can, and do, choose to have children. Consequently, artificial insemination is geared towards heterosexual women; to have access to sperm banks, a lesbian will often have to lie about her sexuality.

Hospital guidelines and health-insurance plans do not recognize a lesbian’s lover and friends as her chosen family. For example, if a lesbian was in a health-emergency situation, her lover/partner would not be able to sign legal consent forms like a heterosexual spouse could. Of course, unmarried heterosexual couples also lack these rights, but at least they have the option of marriage.

These examples portray the heterosexual bias and nuclear-family orientation of the present U.S. health-care system. Because of the health professions’ heterosexism, and because almost all of the medical and mental health professions are indoctrinated with male sexism and stereotypes, lesbian health care has been largely ignored. The medical profession is extremely lacking in knowledge of health issues that affect lesbians and that do not affect heterosexual women, and vice versa. This ignorance promotes and perpetuates myths about lesbians. Heterosexism is the assumption of the superiority and exclusiveness of heterosexual relationships and is one of the cornerstones of male supremacy and sexism. Heterosexual relationships are seen as the norm and homosexuality is either ignored or is seen as deviant. Heterosexism is inextricably tied with homophobia which is defined as the fear of same-sex intimacy. Homophobia also involves the extreme rage, as well as the fear, that many people feel towards homosexuals. The Gay Public Health Workers, a Philadelphia-based group, wrote in 1975:

Homophobia expresses itself in the health field in many ways. The delivery of good health care is adversely affected because homophobia encourages or justifies such practices as: verbal and nonverbal language which alienates gay people and thus interferes with their giving complete histories, their cooperating fully in treatment plans and their accepting preventive services; omission of necessary diagnostic tests for some forms of sexually transmitted diseases; use of electroconvulsive and aversion “therapy” to “cure” homosexuality; denying critically ill patients in intensive care units the emotional support of visits from gay lovers and close friends; overlooking maintenance and outreach methods appropriate to gay people; trying to “treat” homosexuality instead of alcoholism or drug addiction in a gay person with a chemical dependency problem; basing diagnosis or therapy on the assumption of opposite-sex sexual relations; [and] provoking emotional stress and anguish.1

These examples indicate how a woman’s overt or suspected lesbianism is often an interfering factor in receiving adequate health care.

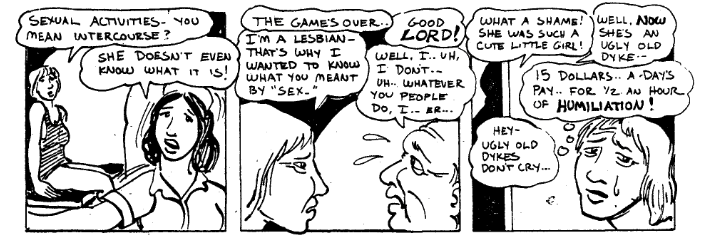

Under these conditions a lesbian is forced to decide whether to come out (identify herself as a lesbian) to her health worker or therapist. This decision presents a double-bind. If she chooses to come out to a doctor, she is often subjected to attempts to humiliate her, to accusations of perversion, or to suggestions that she should see a psychiatrist. Doctors and therapists will often indulge in asking voyeuristic questions about the nature of a lesbian’s sexual activities.

Heterosexism is the assumption of the superiority and exclusiveness of heterosexual relationships and is one of the cornerstones of male supremacy and sexism.

If a lesbian chooses not to come out, the assumption is that she is heterosexual. This assumption may, at times, contribute to the misdiagnosis of her condition based on a lack of information. For example, a lesbian rushed to the emergency room with acute abdominal pain may be diagnosed as either having appendicitis or as having a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, which is pregnancy implanted in the fallopian tube. Knowledge of her lesbianism could, in most cases, disqualify the latter option and could speed up treatment on the appendicitis.

A lesbian who is not out to her doctor is usually asked about her birth-control method and is cornered into lying about her personal life. In this situation, she will not be able to ask questions leading to a better understanding of her specific health needs.

Information and answers to questions about lesbian health needs are scarce due to our society’s historic bias against homosexuality and women. Health care in this country is based on a profit motive. In such a system, it is no wonder that there is inadequate health care for lesbians as well as for women in general, working class people, ethnic and minority groups, and older people.

The myth that the women’s health movement is for heterosexual women must be destroyed…

Health professionals and consumers alike have begun to give more attention to sociopolitical perspectives on health and health-care services; however, the perspective that is now being developed is heterosexual in nature. The medical and mental-health professions have little understanding of the societal pressures that affect lesbians. Stress from living in a heterosexist society can be a cause of health problems, especially emotional ones. In most cases, a lesbian’s visit to a doctor or therapist will exaggerate, rather than allevaite the stress that she experiences as part of her daily life. Lesbians have begun to write about what it is like to be a lesbian in this society, but, as yet, the link between these perspectives and the health care that lesbians receive is only very tentative.

The result of heterosexist and inadequate health care is that often lesbians decide to not seek preventive or even primary health care. Women’s health centers provide a positive alternative for lesbians although only a small percentage of lesbians, and an even smaller percentage of their health needs, can be met by these centers. There are many lesbians involved in working with the women’s health movement. Frances Hornstein, a lesbian feminist working at the Los Angeles Feminist Women’s Health Center, wrote in her pamphlet, Lesbian Health Care:2

The myth that the women’s health movement is for heterosexual women must be destroyed… The idea [for a women’s health movement] was in both the heads of straight women as well as in the heads of lesbians. There was the same exclusion of the needs of lesbians in the early women’s health movement as there was in the women’s movement in general… [Lesbian involvement in the women’s health movement] is important both in an immediate, practical sense as well as in a wider political sense. It was true that the early women’s movement dealt with abortion and contraception. It is naive to think that those issues are irrelevant to us, as lesbians. They are vital to all of us who are feminists in light of the use of women’s bodies by men for their purposes — from rape to population control, two issues that affect every one of us, regardless of our sexuality… The assumption that all lesbians are young, unmarried, childless and healthy is simply incorrect. We have vaginal infections, we have painful menstruation; we have symptoms of menopause… Some of us choose to have children and some of us are still forced to marry and have children. We need women’s medicine as much as any other woman.

Process of Reviewing the Literature

I facilitated a Lesbian Health Issues discussion section for the Female Physiology and Gynecology class at the University of California at Santa Cruz in Spring of 1977. The women in the group compiled and annotated a twenty-two piece bibliography on lesbian health-related articles, books and pamphlets obtained by writing to numerous women’s health centers and lesbian groups in the U.S. Each group or center that responded to our letters knew of only a small fraction of the available literature. The bibliography3 was printed and distributed by the Santa Cruz Women’s Health Collective, of which I am a member.

The literature that we found discussed health issues that affect lesbians gynecologically, emotionally and in regard to reproduction. When reviewing each piece of literature, the Lesbian Health Issues group took into consideration who it was written by and for, and the extent to which, if at all, the author discussed the health situation in a sociopolitical context.

I will discuss the literature we found, more recent literature and other issues in gynecology, reproduction and mental health.

In doing this research, I was assisted by several lesbians, some of whom are health workers or therapists. Also, this article would not exist without the assistance and support of the women in the Santa Cruz Women’s Health Collective.

Gynecology

Considerably more is known about lesbian gynecological health than is available in written form. This knowledge is shared by lesbians involved in the women’s health movement and probably by a few feminist health practitioners. This by no means implies that what is known is complete, nor that the literature that is available is unimportant. However, much more in-depth information and research is necessary on this topic.

The literature which is available to us now has been, for the most part, written by lesbians working in the women’s health movement. This literature provides a good starting point and is often written within a feminist framework. However, the sources are often repetitive in that they draw from each other. There is a necessity for funding to be allocated to lesbian researchers to pursue this area further.

There is also some information on lesbian gynecology in the traditional gynecological medical textbooks; however, it takes quite a lot of searching and reading between the heterosexism to find accurate information.

Three sources on specific lesbian gynecological health that we found are: Lesbian Health Care4 by Frances Hornstein, a nine page booklet; “Information on V.D. for Gay Women and Men” by Julian Bamford in After You’re Out 5; and Health Care for Lesbians 6 by the Chico (California) Feminist Women’s Health Center, a five page fact sheet. These sources state that there are some gynecological health issues that lesbians share with heterosexual women, and some that seem to affect lesbians rarely, if at all. Hornstein7expands on this last category by saying that:

In general, women who do not have sexual relations with men have far fewer problems with maintaining the good health of our genitals, uterus, fallopian tubes and, for that matter, our whole bodies… V.D. in lesbians is very rare. Also, in general, we will find that we [lesbians] are less often bothered with vaginal infections than women who have sexual intercourse with men… Heterosexuality is a serious health hazard for women at this point in time. Because we don’t have to use contraceptives (most of which are experimental and have many dangerous side effects) we are taking a lot fewer risks with our health than women who must be content with inadequate contraception.

Most of the literature includes, to a varying extent, information on vaginal infections (yeast, bacteria, and trichomonas), gonorrhea, syphilis, venereal warts, herpes, crabs (pubic lice) and scabies. Symptoms, treatments, transmission and some prevention are discussed. Most of the information comes from the sharing of experiences in lesbian self-help groups and observations at women’s health centers. There is no mention of the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or urinary tract infections in lesbians. Nor is there any discussion of infections transmitted through the bowel, such as hepatitus, all parasites including amoeba, and bacterial and viral diarrheas which can be a problem for anyone who has oral sex. More in-depth and lesbian-specific information on genital herpes is also necessary. In future presentations on the prevention and treatment of gynecological problems, more information on home remedies and self-health care as an alternative to doctor-dependent diagnosis and chemical treatment would be valuable.

Concerning V.D., the sources state that syphilis and gonorrhea seem to be almost nonexistent in communities of exclusively lesbian women 8. The gonorrhea bacteria can thrive in the cervix, rectum or throat. In theory, if an infected woman has an exceptionally heavy discharge from her vagina (which would provide an environment capable of keeping the bacteria alive outside of the body for a longer period of time than is normal), the bacteria might be passed in sufficient quantity from a finger or tongue to her partner’s cervix or throat. In actuality, however, this seems to be very rare.

Lesbians do get vaginal infections, though perhaps less frequently than heterosexual women. Hornstein suggests that this lowered probability may be due to the way in which certain birth-control methods may increase a woman’s susceptibility to vaginal infections. She adds that the higher incidence in heterosexual women may also be due to the lack of “male hygiene” which could introduce harmful bacteria during coitus. Trichomonas, bacterial infections and yeast can be passed from woman to woman on fingers that are moist with vaginal secretions (2,5). Lesbians, like any other women, can develop a yeast or bacterial infection without any contact with another person. The reasons for this may be related to stress, poor general health or poor hygiene habits.

If the heterosexism of most doctors makes it a personal risk for a lesbian to come out, or, if out, to talk frankly about her lovemaking styles, then knowledge of how vaginal infections, V.D., or other illnesses are passed from woman to woman will not become known.

Certain aspects of lesbian sexuality may relate to gynecological health care. If the heterosexism of most doctors makes it a personal risk for a lesbian to come out, or, if out, to talk frankly about her lovemaking styles, then knowledge of how vaginal infections, V.D., or other illnesses are passed from woman to woman will not become known.

Hornstein9 discusses cervical cancer in relation to lesbians:

There is growing evidence that women who do not have sexual contact with men have less chance of developing cervical cancer than women who have sexual intercourse with men. There are studies that show that certain women have less incidence of cervical cancer than others. Cervical cancer in nuns is almost nonexistent and Jewish women have had a much lower rate of cervical cancer (supposedly due to the fact that Jewish men are circumcized and carry fewer bacteria under the foreskin of the penis). Women who are more likely to develop cervical cancer are women who have had sexual intercourse from an early age and the risk seems to increase for a woman who has had many [male] sexual partners.

Hornstein did not reference the above information; however, references 6-8 mention or discuss the lower incidence of cervical cancer in nuns and reference 8 discusses the incidence in Jewish women.10 Kessler11 discusses the evidence on the possible role of male coital partners in cervical cancer. Rutledge et al.12 state that some categories of women with a higher incidence of cervical cancer are those who married at an early age, those who had coitus at an early age, those who have had a higher number of births, and those who are prostitutes. An extrapolation of these studies may imply that lesbians would have a lower incidence of cervical cancer. However, direct studies of lesbians are needed to verify this implication.

Breast cancer may be a health concern for lesbians and any woman who chooses not to have children. Studies have shown that there is a higher incidence of breast cancer in women who have not had children and in women who have had their first birth after age 30.13

Medical Research and Books on Lesbians and Gynecology

Gynecological medical books are the primary resources of information for the physician and teaching tools for medical students. What these books have to say about lesbians reflect the treatment lesbians are likely to receive. For example, the authors of A New Look at Vulvo-vaginitis,14 put forth a negative view of lesbians. They partially ascribe the increase in V.D. to “the great number of demonstrations and protests for acceptance of male and female homosexuality.” I have yet to see any documentation of how demonstrations can spread V.D., while it is a fact that the incidence of V.D. is lower among lesbians than among the general population.15 The authors’ statement reflects their prejudice as well as their inaccurate assumption that health issues that affect gay men also affect lesbians. Here, as in most medical texts, one must go through this heterosexist and inaccurate information to glean out tidbits of information relevant to lesbians. For instance, in A New Look at Vulvo-vaginitis it is mentioned that trichomonas can be passed vulva to vulva. Unfortunately, when, as in this case, inaccurate and accurate information are mixed together, the differentiation between them can be made only by people who already know the facts. In other words, such books will often not be useful to many doctors or lesbians.

There are a few relatively liberal medical texts such as Gynecology and Obstetrics: Health Care of Women16which essentially describes lesbians as healthy well-adjusted human beings. This book deals with women as whole human beings whose health is integrally related to their social roles and to the pressures on them in a changing society. The text stresses the need for the physician to perceive, accept, and relate to the variety of roles which modern women choose, rather than continuously reinforcing the traditional wife-mother, dependent person role. Even with this attitude, lesbians are mentioned in only about 0.1% of the book which contrasts with the estimate that lesbians comprise 10–12% of the female population. In the remaining percentage of the text, the patient is assumed to be heterosexual. There is no mention of how likely lesbians are to transmit various communicable diseases

The medical profession has conducted a small number of studies on lesbians and health care. These studies have been reported by Lois West, a lesbian involved in the women’s movement, in her article “Lesbian Related Medical Research”.17

West used the Index Medicus, a subject list of published articles in medical literature, to find the research. She notes that “the way lesbians are viewed by the medical establishment is reflected in the difficulty of finding lesbian-related literature in the Index Medicus.” Previous to 1968, the Index Medicus had no mention of lesbians in the subject headings at all. Now the subject heading of “lesbianism” is followed by “see under homosexuality.” West found that most of the articles cited under homosexuality were either about the causes of and cures for homosexuality or about venereal diseases related to male homosexuality.

The articles she found written between 1965 and 1975 that are specifically concerned with lesbians are titled: “Physique and physical health of female homosexuals;” “Homosexual women: an endocrine and psychological study;” “Endocrine functions in male and female homosexuals;” and “Hormonal induction and prevention of female homosexuality” (a study of rat behavior). West states that these articles are problem-oriented and do not discuss gynecological problems that affect heterosexual women and do not affect lesbians, and vice versa.

The larger amount of medical research about male homosexuals as compared with that about lesbians reflects this society’s attitude that women and their activities are less important than those of men…

The larger amount of medical research about male homosexuals as compared with that about lesbians reflects this society’s attitude that women and their activities are less important than those of men and are, thus, less worthy of research by men. Extrapolating the results of studies on male homosexuals to lesbians has created erroneous information in both the medical and mental health professions.

Prejudiced attitudes against lesbians have resulted in a scarcity of information on lesbian gynecological health. Not wanting to deal with the heterosexism of most gynecologists, some lesbians do not seek out health services, and those who do, often do not identify themselves as lesbians. This enforced invisibility creates a downward spiral in which the negative attitudes towards lesbians promote further lack of knowledge, which then creates inadequate health care.

Reproduction

Related to gynecology, yet distinct from it, is the issue of reproduction, on which very little has been written. There is a prevalent assumption that lesbians do not have children or that lesbians who do have children had them before they came out. Actually, a significant number of lesbians have children, possibly as many as one-third.18

Lesbians who want to have children can either artificially inseminate themselves or can engage in coitus with a man. Access to sperm banks requires the assistance of a medical doctor, and usually a lesbian will

have to lie about her sexuality and lifestyle to obtain this service. Some lesbians have begun experimenting with “home methods” of artificial insemination using the sperm of a willing donor collected in a condom and transferred to the vagina. The transferring process may involve the use of a diaphragm or any pipette-like object.

If you want to experiment with artificial insemination, remember that daylight irreparably damages the sperm and that it must be used very soon after collecting unless you are able to store it via a sophisticated method of freezing.19

There is very little information available on artificial insemination other than that which I have mentioned above. Nor is there literature that deals with the harrassment lesbian mothers and their children receive from the medical profession, such as during visits to pediatricians.

In “Radical Reproduction: X without Y”,20 Laurel Galana discusses a method of sex determination previous to conception and potential future methods of female reproduction without men, such as parthenogenesis and cloning. Cloning is the transplantation of the genetic material from one body cell into an egg cell which has had its genetic material removed. This process in frogs has produced a frog “offspring” genetically identical to the frog that donated one of its body cells. Parthenogenesis is female asexual reproduction, that is, the development of the egg without the sperm, which will always result in a female offspring. However hypothetical parthenogenesis is for humans, it is a natural form of reproduction in a worm-like animal called a rotifer.21 Galana cites the work of two researchers who in 1940 succeeded in bringing one rabbit (out of 200 tested) to fullterm by means of parthenogenesis. Appended to Galana’s article is a list of sources that will be valuable to others pursuing this field.

Robert Francoeur in Utopian Motherhood New Trends in Human Reproduction22also discusses many of these potential reproductive methods. However, because of his nonfeminist and apolitical consciousness, this book is relevant to lesbians only as a reference source.

In view of the fact that most of the research on reproduction is being done by men, some of whom are blatant about their motives to produce only male children, Galana says to all women:

Whatever our feelings, whether we are morally repelled by this kind of tampering with nature or sure we never want children anyway, or are content to have them by the usual method, none of us can afford to ignore the potential (for good and/or evil) which is developing in the scientific laboratories. We can only hope that women will see that this is a new but crucial political battleground — one we can’t afford to walk away from.23

Mental Health

The close relation of mental and physical health is a concept that is rapidly becoming more accepted in our society, although the actual widespread use of this concept in the medical or psychological health professions is still quite a ways off.

The search for literature on lesbians and therapy was not a primary focus of the Lesbian Health Issues group, though we did review some of the available literature. There are several varying degrees to which the mental health profession manifests its heterosexism and homophobia towards lesbians (and gay men):

Persecution: Lesbianism is viewed as repulsive and as a sickness in itself; to be cured means to become heterosexual. Treatments to change homosexual behavior have included, and to some extent still include, lobotomies, electroshock, aversion and hormonal “therapy,” and behavior modification. Many therapists still assume that a woman’s lesbianism is the root cause, or the result of, her emotional problems. Since mental health professionals are often the spokespeople who determine “one’s fitness” in society, judgment of lesbians by therapists can lead to discrimination, especially in employment and child custody.

Tolerance: Tolerance is the gift of the superior to the inferior. Lesbianism is viewed as infantile and as a stage that will be grown out of. Heterosexuality is considered more mature. Another aspect of tolerance is that lesbians are pitied because they are not “normal.”

Acceptance: Lesbian struggles and identity are made invisible. “To me you’re not a lesbian, you’re just a person.” “It’s your business who you sleep with.” This is the attitude of the so-called liberal therapists who do not see the political significance of lesbianism nor do they understand the cultural importance of a lesbian lifestyle.

It has not been a priority for the mental health profession to recognize and understand the stresses that lesbians experience…

Stress

It has not been a priority for the mental health profession to recognize and understand the stresses that lesbians experience which are related to living in a society that condemns and misunderstands homosexuality. It is even questionable, at this time, if nonlesbian therapists, no matter how sincere and informed, can fully support and understand lesbian clients, and validate their strength in surviving.

One source of stress that affects lesbians is the internalization of heterosexism and homophobia. To identify oneself as homosexual is to immediately identify with a group that is hated and despised by all racial, religious, and ethnic groups — even one’s own. Any internalization of this hatred affects a lesbian’s self-image and can often result in feelings of guilt. Daily social ostracism also occurs. Visible lesbians are treated as outcasts or queers. They are ignored, fantasized about, and played with. Lesbians are subject to verbal and physical harassment. Closeted lesbians live in fear of being found out. A lesbian’s family may be a source of stress for her as coming out to one’s family can often mean risking anger, pain, or exile. Drifting apart from one’s family may be the result of not coming out. The process of redefining relationships and roles with one’s lover is often a stressful as well as a liberating process. Having seen the inadequacy of the male-female (butch-femme) role models, many lesbians are struggling to create new, intimate, role models for relationships.

Lesbians may encounter discrimination in employment. A woman can be legally fired from her job in some cases for being a lesbian, and in others she may be harassed so intensely that she will be forced to quit. A handbook published by the U.S. Department of Labor in 1971 states that in 42 states, homosexuals cannot legally pursue the following licensed professions (this is a partial listing): accountant, attorney, beautician, chiropractor, electrician, firefighter, insurance agent, lawyer, pharmacist, plumber, registered nurse, state trooper, taxicab driver, and veterinarian.

For most lesbians their job is their only source of income. In our society it is assumed that all women are married or are otherwise dependent on a man for financial support. This assumption is used to justify the secondary position of the working woman and to justify women’s lower pay and last-to-hire, first-to-fire status. Furthermore, this assumption puts lesbians and single women in a stressful, tenuous financial and career situation.

The issue of lesbian motherhood and lesbianism among adolescents also represents sources of stress. As mentioned earlier a significant number of lesbians have children, possibly as many as one-third. Many custody cases have ruled against lesbians as being “unfit” mothers, or the authorities have made lesbians choose between their lovers and their children. An adolescent’s lesbianism is often dismissed by therapists, parents, and educators as a “stage” which will be grown out of. Not only is this attitude unsupportive of the adolescent’s present feelings but it can cause her much stress when she reaches adulthood and has not “outgrown that stage.” Also, therapy for adolescents is usually contingent on parental consent; most parents won’t let their teenager see a lesbian therapist.

To summarize on the stresses that lesbians experience in this society:

Can you understand that the pain a woman experiences is not inherent in her lesbian relationship; the relationship itself is seen as beautiful and supportive. The sham, having to lie, the constant fear of disclosure followed by rejection, the alienation and feeling that no one understands comprise the source of pain.24

And in spite of this pain, for lesbians and gay men:

It is a phenomenal act of courage and self assertion to accept and own a part of oneself that society says is “sick” — and you know inside it is not, and you are not, and you are the only authority for that decision.25

Gay Health Workers

The health field, and society in general, suffer a loss when heterosexism and homophobia restricts or eliminates opportunities of gay people to make their optimal contributions as health workers. Escamilla-Mondanaro26 says the following about lesbian therapists, but her passage can be applied equally as powerfully to lesbian doctors or health practitioners:

Lesbian therapists must come out! “Every time you keep your mouth shut you make life that much harder for every lesbian in this country. Our freedom is worth your losing your jobs and your friends”27… There is only one way for mental health centers and schools to demonstrate their good faith to the lesbian community, and that is to hire lesbian therapists and faculty… Lesbians can facilitate the hiring of lesbian therapists by sitting on the advisory boards to community mental health centers. The lesbian community must evaluate all services offered to lesbians, and advise women as to the sincerity and efficacy of these programs.

Solutions for the Future

Working towards solutions to the lack of adequate health care for lesbians can be focused in at least two directions:

- Pressuring the health professions to educate themselves on the validity of lesbianism as a lifestyle. It is important for every doctor or psychologist to know the facts about lesbianism that are relevant to her or his specialization. As mentioned earlier, there is a necessity for funding to be allocated to lesbian researchers so that more current and in-depth statistics can be compiled on lesbian health. It is also necessary for pressure to be put on professional medical, public health, and mental health schools to admit open lesbians into their training programs.

- Developing and participating in alternative lesbian, feminist, or socialist/feminist health centers and counseling centers. This is important for creating environments where lesbians will feel comfortable and validated. Such centers are also important in their employment of lesbian health workers or therapists.

Both of these directions require self-education about lesbians’ specific health needs. Both also require a political analysis and framework in which to see that changes in the medical profession’s heterosexism will come about only with changes in our society as a whole. With such an analysis, lesbians can see that their experiences with the health care system are not isolated and can organize for change.

Education is one of our most valuable tools. Myths about lesbians thrive on ignorance, and prejudice has its basis in the misinterpretation of facts. In the realm of health care, it is important for lesbians to re-direct the interpretation and teaching of science, medicine, and psychology. Biased interpretation of research continues to perpetuate notions of female inferiority and of homosexual perversion. Even progressive university classes on female health care continue to teach about V.D. and reproduction only in terms of heterosexuality. Science can be a tool for us to better understand our selves and the universe. As it is used now, it is a tool to perpetuate the power imbalances and oppressive ideologies of our culture.

Lesbian-related research and constructive health care will increase with the growing number of lesbians who are proud of their sexuality and lesbian feminists who see lesbianism as a political as well as sexual Identification.

ANNOTATED LITERATURE LIST ON LESBIAN HEALTH

Lesbians and Therapy: Experiences and Critiques

Josette Escamilla-Mondanaro’s “Lesbians and Therapy” and Barbara Sang’s “Psychotherapy with Lesbians: Some Observations and Tentative Generalizations,” both in Psychotherapy for Women: Treatment Toward Equality28 provide excellent consciousness-raising material on the needs of lesbian women who seek therapy. Both authors are therapists and lesbians. The articles are valuable and readable for professionals and non-professionals alike.

“Lesbians and the Health Care System”29 by the Radicalesbians Health Collective is a very strong statement about the mistreatment of lesbians by therapists. The article relates the personal experiences of seven lesbians in therapy.

“The Psychoanalysis of Edward the Dyke”30 by Judy Grahn — a humorous and bitingly sarcastic short story.

“The-Rapist: Lesbians and Psychiatry” — a short passage in the widely available Our Bodies, Ourselves.31

Karin Wandrei, a lesbian feminist, conducted a constructive study, “Lesbians in Therapy”32 in which she reports on how lesbians perceive their experiences in therapy.

In “Oppression is Big Business: Scrutinizing Gay Therapy” 33, Karla Jay discusses the relationship between lesbian therapist and their clients. She points out that although lesbians are rightfully wary of the traditional therapists, they cannot assume that all gay therapists will be acceptable. She offers a list of criteria for choosing a therapist and encourages clients to go into therapy with an informed and critical attitude.

Don Clark, in Loving Someone Gay34, discusses the role of psychotherapists and counselors in “helping someone gay.” His twelve therapeutic guidelines for mental health professionals working with gay clients are very valuable.

Psychology of Lesbianism

Love Between Women35by Charlotte Wolff offers a historical presentation of the early psychoanalytic theories on lesbianism. Wolff partially aligns herself with the belief that the essence of lesbianism is emotional incest with the mother. Although she has some understanding of social pressures confronting lesbians, much of her theory is misinformed and outdated.

Although the bulk of Phyllis Chesler’s book, Women and Madness36, is highly valued by feminists and therapists, her chapter on lesbians is shallow and disappointing. A constructive aspect of this chapter is that Chesler discusses how many clinician-researchers have confused lesbianism with male homosexuality.

“Psychological Test Data on Female Homosexuals: A Review of the Literature”37 by B. Riess et al. is a critical and comparative academic review of the studies before 1974 on lesbians. Much of the data is contradictory but the evidence indicates that lesbians “seem to differ… in psychodynamics” from male homosexuals and that lesbians have no more psychopathology than heterosexual female controls.

One important sub-category of lesbian psychology is that of third world lesbians and their relationship to their cultures. An insightful article on this topic is “The Puerto Rican Lesbian and Puerto Rican Community”38 by N. Hildalgo and E. Christensen.

Psychology of Homosexuality

The literature mentioned in this section does not specifically deal with lesbians, but rather with gay people in general, sometimes with an emphasis on gay men. For this reason, lesbians, and therapists working with lesbians, will find that the literature varies in value and relevancy.

“Far From Illness: Homosexuals may be Healthier than Straights”39 was written by Mark Friedman, a gay psychologist. Friedman discusses the changes taking place in the traditional views held by psychologists towards homosexuality. He includes studies that help show that homosexuality is not only normal, but that in some ways, gays may actually function better than nongays. Friedman also wrote a valuable article on “Homophobia”40, and a book, Homosexuality and Psychological Functioning.41

In Society and the Healthy Homosexual42, George Weinberg discusses, among other topics, gay people and therapy, coming out to parents, and what his idea of a healthy homosexual is. Weinberg presents aspects of the heterosexism in the mental health system. However, he believes that lesbians do not have as much difficulty in surviving as gay men and he deals very little with the problems of traditional sex roles which are inherent in heterosexism.

The Journal of Homosexuality43 is written for mental health and behavioral science professionals. It is very academic and has the most recent research. The Homosexual Counseling Journal44 is geared to counseling and therapy issues.

In Etiological and Treatment Literature on Homosexuality45, Ralph Blair points out that no one knows the causes of homosexuality, though obviously, many people have tried to find reasons and causes. To fairly question the cause of homosexuality, the cause of heterosexuality must equally be questioned.

Lesbian Adolescents

Growing Up Gay46 by Youth Liberation presents a dozen articles about the experience of being young and gay, including accepting one’s own gayness, and coming out and talking with parents. Extensive resources are appended.

High School Women’s Liberation47 by Youth Liberation includes articles on lesbianism.

Learning About Sex48 by Gary Kelly is a standard, school textbook that takes a positive view of homosexuality.

Mondanaro49 briefly summarizes some of the issues involved for lesbian adolescents from a therapist’s viewpoint.

Parents of Gays by Betty Fairchild50 and “A Psychiatrist Answers Teen Questions About Homosexuality”51, by Robert Gould in Seventeen magazine also relate to this topic.

Lesbian Mothers

By Her Own Admission: A Lesbian Mother’s Fight to Keep her Son52, by Gifford Gibson.

“Lesbian Mother” by Jeanne Perreault in After You’re Out53.

The bibliographic information for the following articles is listed in A Gay Bibliography54:

R.A. Basile, “Lesbian Mothers I and II.”

Carole Klein, “Homosexual Parents.”

“The Avowed Lesbian Mother and Her Right to Child Custody: A Constitutional Challenge That can no Longer be Denied,” in the San Diego Law Review.

Nan Hunter and Nancy Polikoff, “Custody Rights of Lesbian Mothers: Legal Theory and Litigation Strategy.”

Dolores Klaich, “Parents Who Are Gay.”

Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, “Lesbian Mothers.”

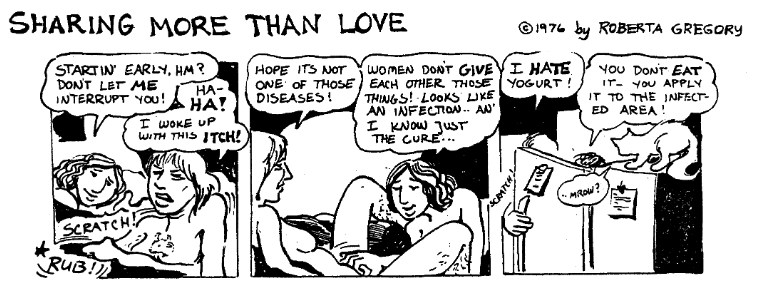

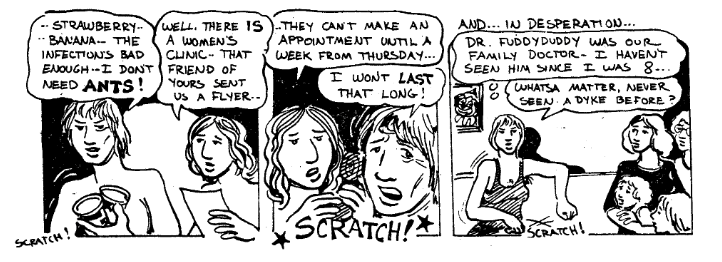

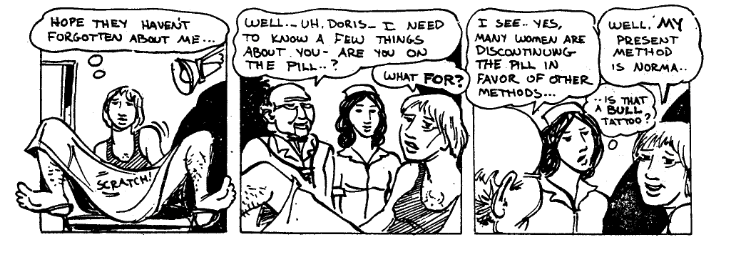

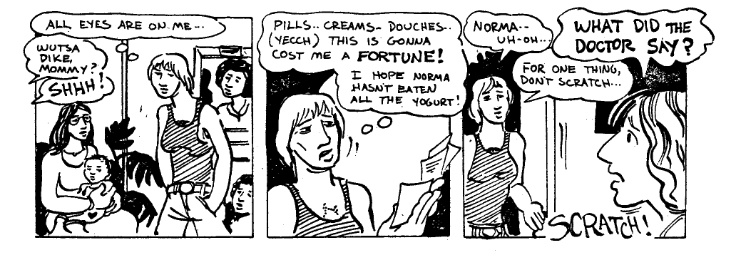

We’d like to thank Roberta Gregory for the use of the strip “Sharing More Than Love.” The strip is an excerpt from Dynamite Damsels. a women’s comic book published by the artist and available for $1 from Roberta Gregory, PO Box 4192, Long Beach, CA 90804.

Editorial Note: Mary O’Donnell wants to mention that the use of flavored yogurt, as described in this comic strip is only a literary liberty and definitely not recommended in actual practice. Use only plain, unflavored, unsweetened yogurt, please.

>> Back to Vol. 10, No. 3 <<

REFERENCES

- Gay Public Health Workers (1975). “Heterosexuality: Can It Be Cured?” Available from Gay Public Health Workers, 206 N. 35th St., Philadelphia, PA, 19104.

- Hornstein, Frances (1973). Lesbian Health Care. Available from Feminist Women’s Health Center, 1112 Crenshaw, Los Angeles, CA, 90019.

- Santa Cruz Women’s Health Collective (1977). Lesbian Health Issues (annotated and unannotated forms available). Available from Santa Cruz Women’s Health Center, 250 Locust St., Santa Cruz, CA, 95060.

- Hornstein, Frances (1973). Lesbian Health Care. Available from Feminist Women’s Health Center, 1112 Crenshaw, Los Angeles, CA, 90019.

- Bamford, Julian (1975). “Information on VD for Gay Women and Men.” In: After You’re Out: Personal Experiences of Gay Men and Lesbian Women (1975), ed. by Karla Jay and Allen Young, Links (Quick Fox). Also available in pamphlet from the Gay Community Services Center, 1614 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA, 90017.

- Lesbian Self-Help Group. Health Care for Lesbians. Available from the Chico Feminist Women’s Health Center, 330 Flume St., Chico, CA, 95926.

- Hornstein, Frances (1973). Lesbian Health Care. Available from Feminist Women’s Health Center, 1112 Crenshaw, Los Angeles, CA, 90019.

- Hornstein, Frances (1973). Lesbian Health Care. Available from Feminist Women’s Health Center, 1112 Crenshaw, Los Angeles, CA, 90019;Bamford, Julian (1975). “Information on VD for Gay Women and Men.” In: After You’re Out: Personal Experiences of Gay Men and Lesbian Women (1975), ed. by Karla Jay and Allen Young, Links (Quick Fox). Also available in pamphlet from the Gay Community Services Center, 1614 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA, 90017;Lesbian Self-Help Group. Health Care for Lesbians. Available from the Chico Feminist Women’s Health Center, 330 Flume St., Chico, CA, 95926.

- Hornstein, Frances (1973). Lesbian Health Care. Available from Feminist Women’s Health Center, 1112 Crenshaw, Los Angeles, CA, 90019.

- Fraumeni, J.F. et al. (1969). “Cancer Mortality Among Nuns.” Journal of National Cancer Institute. Vol. 42, p. 455; Towne, J.E. (1955). “Carcinoma of the Cervix in Nulliparous and Celibate Women.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 68, p. 606; Kessler, Irving I. (1976). “Human Cancer as a Venereal Disease.” Cancer Research. Vol. 36, p. 783.

- Kessler, Irving I. (1976). “Human Cancer as a Venereal Disease.” Cancer Research. Vol. 36, p. 783.

- 9

- Baker, R. Robinson, ed. (1977). Current Trends in the Management of Breast Cancer. Johns Hopkins University Press; MacMahon, Brian et al. (1970). “Age at First Birth and Breast Cancer Risk.” Bulletin of World Health Organization. Vol. 43, p. 209.

- Cisley, L.J. and S.C. Kasdon (1971). A New Look at Vulvovaginitis. Searle & Co., Medical Dept., Box 5110, Chicago, Ill., 60680.

- Hornstein, Frances (1973). Lesbian Health Care. Available from Feminist Women’s Health Center, 1112 Crenshaw, Los Angeles, CA, 90019.

- Romney, S. et al (1975). Gynecology and Obstetrics: The Health Care of Women. McGraw-Hill.

- West, Lois. Lesbian-Related Medical Research. Available from Women’s Community Health, 137 Hampshire St., Cambridge, MA 02139.

- Escamilla-Mondanaro, Josette (1977). “Lesbians and Therapy,” In: Psychotherapy for Women, ed. by Edna Rawlings and Dianne Carter. Charles C. Thomas, Publisher. Also found in Issues in Radical Therapy, Vol. 3, No.3, Summer 1975.

- Galana, Laurel (1975). “Radical Reproduction: X without Y,” in: The Lesbian Reader, ed. by L. Galana and G. Covina. Amazon Press, 395 60th St., Oakland, CA, 94618.

- Galana, Laurel (1975). “Radical Reproduction: X without Y,” in: The Lesbian Reader, ed. by L. Galana and G. Covina. Amazon Press, 395 60th St., Oakland, CA, 94618.

- Communications Research Machine, Inc. (1972). Biology Today. J.H. Painter, Jr., Publisher, page 771.

- Francoeur, Robert (1970). Utopian Motherhood — New Trends in Human Reproduction. Doubleday.

- Galana, Laurel (1975). “Radical Reproduction: X without Y,” in: The Lesbian Reader, ed. by L. Galana and G. Covina. Amazon Press, 395 60th St., Oakland, CA, 94618.

- Escamilla-Mondanaro, Josette (1977). “Lesbians and Therapy,” In: Psychotherapy for Women, ed. by Edna Rawlings and Dianne Carter. Charles C. Thomas, Publisher. Also found in Issues in Radical Therapy, Vol. 3, No.3, Summer 1975.

- Meyer, Sybil (1977), Creative Arts Therapist. Personal communication, Santa Cruz, California.

- Escamilla-Mondanaro, Josette (1977). “Lesbians and Therapy,” In: Psychotherapy for Women, ed. by Edna Rawlings and Dianne Carter. Charles C. Thomas, Publisher. Also found in Issues in Radical Therapy, Vol. 3, No.3, Summer 1975.

- Brown, Rita M. (1972). “Take a Lesbian to Lunch,” In: Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation. Douglas-Links (Quick Fox).

- Galana, Laurel (1975). “Radical Reproduction: X without Y,” in: The Lesbian Reader, ed. by L. Galana and G. Covina. Amazon Press, 395 60th St., Oakland, CA, 94618.

- Communications Research Machine, Inc. (1972). Biology Today. J.H. Painter, Jr., Publisher, page 771.

- Francoeur, Robert (1970). Utopian Motherhood — New Trends in Human Reproduction. Doubleday.

- Abbott, Sidney and Barbara Love (1972). Sappho Was a Right-On Woman: A Liberated View of Lesbianism. Stein & Day.

- Altman, Dennis (1971). Homosexuality: Oppression and Liberation. Avon Books.

- Jay, Karla and Allen Young, eds. (1975). After You’re Out: Personal Experiences of Gay Men and Lesbian Women. Links (Quick Fox).

- Clark, Don (1977). Loving Someone Gay. Celestial Arts, 231 Adrian Rd., Millbrae, CA, 94030.

- Wolff, Charlotte (1971). Love Between Women. Harper & Row.

- Chesler, Phyllis (1972). Women and Madness. Avon Books.

- Riess, B. et al. (1974). “Psychological Test Data on Female Homosexuals: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Homosexuality, Vol. 1, No. 1. Haworth Press, 174 Fifth Ave., New York, NY, 10010.

- Hildalgo, H. and E. Christensen (1976). “The Puerto Rican Lesbian and the Puerto Rican Community.” Journal of Homosexuality, Vol. 2, No. 2, Winter 1976-77. Haworth Press, 174 Fifth Ave., New York, NY, 10010.

- Freedman, Mark (1975). “Far From Illness: Homosexuals May be Healthier Than Straights.” Psychology Today, March 1975.

- Freedman, Mark (1976). “Homophobia.” 8/ueboy, Vol. V, April 1976. Also available from National Gay Task Force, Rm. 506, 80 Fifth Ave., New York, NY, 10011.

- Freedman, Mark (1971). Homosexuality and Psychological Functioning. Brooks-Cole.

- Weinberg, George (1972). Society and the Healthy Homosexual. St. Martin’s.

- Journal of Homosexuality. Haworth Press, 174 Fifth Ave., New York, NY, 10010.

- Homosexual Counseling Journal. 30 E. 60th., New York, NY, 10022.

- Blair, Ralph (1972). Etiological and Treatment Literature on Homosexuality. The Otherwise Monograph Service. The Homosexual Community Counseling Center, Inc., 30 East 60th St., New York, NY, 10022.

- Youth Liberation. Growing Up Gay and High School Women’s Liberation. Youth Liberation, 2007 Washtenaw Ave., Ann Arbor, Michigan, 48104.

- Youth Liberation. Growing Up Gay and High School Women’s Liberation. Youth Liberation, 2007 Washtenaw Ave., Ann Arbor, Michigan, 48104.

- Kelly, Gary F. (1977). Learning About Sex (revised edition). Barron’s Educational Service, 113 Crossways Park Dr., Woodbury, NY, 11797.

- Escamilla-Mondanaro, Josette (1977). “Lesbians and Therapy,” In: Psychotherapy for Women, ed. by Edna Rawlings and Dianne Carter. Charles C. Thomas, Publisher. Also found in Issues in Radical Therapy, Vol. 3, No.3, Summer 1975.

- Fairchild, Betty (1975). Parents of Gays. Lambda Rising, 1724 20th NW, Washington, DC, 20009.

- Gould, Robert (1977). “A Psychiatrist Answers Teen Questions About Homosexuality.” Seventeen, September 1977.

- Gibson, Gifford Guy (1977). By Her Own Admission: A Lesbian Mother’s Fight to Keep Her Son. Doubleday.

- Perreault, Jeanne (1975). “Lesbian Mother,” In: After You’re Out: Personal Experiences of Gay Men and Lesbian Women, ed. By Karla Jay and Allen Young, Links (Quick Fox).

- Task Force on Gay Liberation (1975). A Gay Bibliography. Task Force on Gay Liberation, American Library Association, Box 2383, Philadelphia, PA, 19103.