This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Book Review—Jungle Law: Stealing the Double Helix

by Judy Strasser

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 8, No. 5, September/October 1976, p. 29–31

A review of Anne Sayre’s Rosalind Franklin and DNA, (W.W. Norton, 1975).

Judy Strasser does free-lance writing and is particularly interested in the land-reform struggles now going on in the San Joaquin Valley, California. She participated in the campaign against the Stanford Research Institute during the Vietnam War and is now living in Madison, Wisconsin with her one-year-old son and her husband.

What motivates scientists to do tedious experiments, chemical dishwashing, mathematical manipulations that often lead nowhere? An aura of intellectual romance shrouds the scientific world. It hides scientists’ daily routines from public view, and mystifies the reasons they choose the work they do. For most people, the politics and economics of science-the decisions about who gets funded and who does not-simply do not exist. Nonscientists think that scientists tackle certain intellectual puzzles simply because they (like mountains) are there; or that scientists, guided by humanitarian impulses, turn their talents to pressing social problems.

A few years ago, I attended a conference as a nonscientist observer. A comer of the mystifying veil lifted and taught me a lesson about scientific motivation. The conferees represented many disciplines, though they all worked on related problems. They seemed to divide themselves into two groups. The larger consisted of older men from rather ordinary applied sciences. The applications were agricultural, and I found that I could usually follow the gist of their arguments despite my scientific ignorance. The smaller group included the young hotshots: a select batch of new-and almost-Ph.D.s, perhaps two dozen men and two women from a few top institutions. They all worked in a “pure” and glamorous field. Their papers impressed me with their unintelligibility, and I was apparently not alone. The moderator of their panel apologized profusely-but, I thought, with considerable pride-for the obscure vocabulary required to discuss or understand his rarified discipline.

Outside the conference sessions, these young scientists stuck pretty much to themselves, talking shop with vehemence. They obviously felt their particular branch of science superior to the others represented at the conference. Obviously too, they were engaged in intense competition among themselves. I heard tales of intrigue, of institutional infighting, of personal antagonisms. I heard about concealed data and spy-like visits to laboratories. I heard half-serious schemes of sabotage. I also heard, from more than one person, that the object of their scientific attentions was a Nobel Prize.

I began to feel that I was reliving James Watson’s scientific potboiler, The Double Helix (Atheneum, 1968; Mentor paperback, 1969), a book I had read with enthusiastic interest several years earlier. Apparently Watson told it not only as it was, I thought, but as it is. I was in the middle of one of those breathless neck-and neck races for scientific glory. It seemed as thrilling as Watson makes it sound.

Anne Sayre’s book, Rosalind Franklin & DNA, revived my memories of that conference. Sayre wrote her book to refute Watson’s cruelly distorted picture of Franklin’s role in determining the structure of DNA, the stunning scientific accomplishment for which Watson, his coworker Francis Crick, and Franklin’s co-worker Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize. (The Prize is not awarded posthumously, and it is never divided more than three ways. Rosalind Franklin’s premature death relieved the Nobel committee of the decision whether she merited the award.)

Using materials gathered during extensive interviews of people who knew both Franklin and James Watson in the early 1950s, and evidence from Watson’s own book, Sayre shows how the Nobel laureate transformed a superb, dedicated woman scientist into an ugly caricature. The fictional Rosy of The Double Helix, Sayre writes, is “the perfect, unadulterated stereotype of the unattractive, dowdy, rigid, aggressive, overbearing, steely, ‘unfeminine’ bluestocking, the female grotesque we have all been taught either to fear or to despise.”1

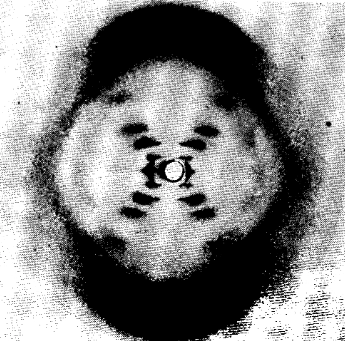

Sayre sets the record straight in a convincing, compelling biography. Rosalind Franklin was a brilliant scientist, passionate about her work, motivated, according to Sayre, by a fierce love of truth and dedication to the methods of scientific inquiry. Her crystallographic work provided basic data used by Francis Crick and James Watson in building their famous DNA molecule in February, 1953. Franklin had suggested in late 1951 that the molecule probably had a “helical structure” containing 2, 3, or 4 chains and “having the phosphate groups near the outside.”2 A year later, Watson and Crick obtained (without Franklin’s knowledge) crucial experimental data she had developed: her X-ray photograph of the hydrated B form of DNA, which provided clear evidence of the helix and its diameter; her density data indicating the possibility of a two-chain molecule, and other information that convinced Watson that the nucleotide bases are in the center of the molecule with the sugar-phosphate groups forming a backbone outside.3 These data immeasurably aided Watson and Crick’s efforts at model-building.

Sayre notes that since Franklin’s death, a “gentle robbery” has stripped her of credit for these important contributions. The British Museum exhibit of the DNA molecule, for example, omitted her from the list of people who contributed to discovering the structure, until her friends complained. Several encyclopedia and journal articles about DNA barely mention her accomplishments. Rosalind Franklin & DNA would be an important book even if Sayre did no more than bring to the public’s attention the work of this neglected scientist.

But Anne Sayre does much more. Her biography explores the inherent sexism in the rigidly hierarchical scientific world of post-World War II England, a sexism which made Rosalind Franklin, who merely demanded professional equality with her male colleagues, seem to many an outraged feminist. The book documents James Watson’s sexist attitudes. (His own book corroborates and expands Sayre’s claims on this point.) Sayre also builds a good case for Watson as a scientific thief. She convincingly argues that the laureate built his molecular model and his reputation on Rosalind Franklin’s data without crediting the source.

Finally, Sayre suggests that Watson, when writing The Double Helix, invented Rosy to “rationalize, justify, excuse, and even to ‘sell”‘ a new brand of scientific ethics.4 Sayre argues that Watson was forced to create an impossible woman who stood as an obnoxious impediment to scientific progress, in order to explain away behavior which violated the accepted standards of the scientific community.

Sayre, it seems to me, strains to make this final point. The strain is evident in her writing throughout the book, and it weakens the entire work. At first I thought that her hammering insistence on certain points, and her sometimes strident pleas for the reader’s belief came from her worry that, as a nonscientist and a friend of Franklin’s, she would be accused both of misunderstanding scientific facts and of outright bias. She feared, perhaps with good reason, that no one would accept her refutation of a best-selling book by a Nobel Prize winner. But when, in her Afterword, I read her accusation that Watson reduces the “ethics of science” to “roughly the same as those of used-car dealers,” I realized that the strain comes from Sayre’s confused understanding of how and why science is done.5

Life in the Science Jungle

Sayre describes the highly competitive world of Western science in glowing terms. This, it seems to me, is a major error and the-source of the book’s weakness. “Ideally, all problems should be available to all comers on an open, competitive market,” she writes.6 “Rivalry is stimulating and useful, and this is the way in which science works,” she adds a few lines later.7 Sometimes, she explains, when time is short, problems are many and pressing, or funds are limited, scientists agree to restrict themselves to specific problems. But she concludes that the “free-market approach to science” is the best, “for research is too creative a business to profit from being narrowly channeled. “8

Scientific progress, she notes, demands continual communication of hunches, hypotheses, methods, and results. Sayre suggests that the tension that results from the need for communication in a highly competitive atmosphere can be relaxed only if scientists accept the highest standards of honesty, decency, and devotion to truth. Certain accepted traditions therefore rule western science; for example, a moral imperative that researchers credit the sources of their ideas. Sayre says that “a body of practice, etiquette, manners, which is generally subscribed to” allows scientists to trust each other-to communicate their most recent results to their most intense competitors, safe in the conviction that they will not be scooped.9

Sayre accuses Watson not only of violating this unwritten civilizing code of the scientific jungle, but of encouraging others to imitate his unethical behavior. She reports that in an informal poll at the State University of New York’s Stony Brook campus, one graduate student told her that the way to “get on” in science is “to keep your mouth and your desk drawers locked, your eyes and ears open, and ‘then beat the other guy to the gun.’ … Another graduate student said that it was all down in The Double Helix, how to get ahead, and nobody thought the worse of Watson, did they?”10

These students-and also some of the ambitious young hotshots at the conference I observed-share with the young Watson a hunger for glory motivated neither by love of truth nor love of humanity. They too spurn (at least in their bragging banter) the traditional rules of scientific competition and fair play which Anne Sayre desribes. But neither they nor Watson should be blamed for the “crumbling” of the “rules which for years have worked fairly well to keep the competition civilized.”11

The competitive structure of western scientists to strive for the glory, the power, the research money which accompany success. James Watson apparently felt the rewards well worth breaking a few unwritten rules. He acknowledges self-interest as his own motivation in The Double Helix. He had dreams of fame when he first approached the DNA problem.12 Later, he explained to an acquaintance that he “was racing [Linus Pauling] for the Nobel Prize.”13 When he and Crick thought they had solved the problem, Watson reports, Crick was eager to build the model and report the solution to other scientists so that they could redirect their work to incorporate the newly discovered, exciting DNA structure. Watson confesses that he was “equally anxious to build the complete model,” but “thought more about Linus and the possibility that he might stumble upon the base pairs before we told him the answer” than about other scientists’ work, or the progress of science in general.14

Watson’s self-portrayal is disgusting; more so when contrasted with Sayre’s portrayal of Rosalind Franklin’s character and apparently selfless motivation. It does seem wrong that he should play dirty and win; that she, playing fair, would lose. But Sayre herself calls science· a jungle. Watson and his young admirers play by the jungle’s law. Moralizing will not prevent such things. Sayre would do better to attack the problem at its root: the competitive, hierarchical structure of western science which rewards arrogance, sexism, and cheating.

Judy Strasser