This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

New Biotechnologies Suggest New Weapons: The Next Generation of Biological Weapons

by Alexander Hiam

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 14, No. 3, May-June 1982, p. 32 — 35

Alexander Hiam is a science writer and consultant to biotechnology companies. He has written on the commercial and social impacts of genetic engineering.

The U.S. Department of Defense is rapidly expanding a research program to utilize new advances in biotechnology-recombinant DNA (recDNA) and hybridoma technology–for the creation of new biological weapons (BW). Many of the problems which limit the uses of conventional BW agents, such as danger to the users, lack of specificity, unpredictable dispersal and effectiveness, can be overcome with the new biotechnologies. The new generation of BW may well be so sophisticated and deadly, and yet so simple to use, that they will be used. It is therefore imperative that research programs be challenged before a new generation of biological weapons is fully developed.

Officially, since 1969, chemical and biological warfare research has been restricted to “defensive” purposes. Yet in 1977, a series of Senate hearings revealed the continuing development and large-scale production of antipersonnel, antianimal, and anticrop agents.1 Since then a number of reports have provided additional evidence of the continuing BW activities of the U.S. military.2

The Department of Defense has stockpiled many organisms which are pathogenic in humans, such as anthrax, tularemia, salmonellosis, tuberculosis, and Valley Fever. A. Conadera, in a recent Science for the People article, observed that the organisms Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Coccidioides immitis (which cause tuberculosis and Valley Fever) have both been shown to pose greater health risks for blacks than whites.3 The fact that the army has chosen to stockpile these two organisms underlines one goal of BW research: weapons which can be targeted to specific national or racial groups.

Antipersonnel, Antianimal, Anticrop

The most sinister potential application of recDNA and other new biotechnologies is the refinement of race-specific agents. The traits which make certain BW agents slightly race-specific could be identified, amplified, and transferred to other agents using newly developed techniques. It might be possible to develop new kinds of specific agents in this way, or to engineer BW agents which would produce toxins only in combination with substances in a food item unique to a target group.

RecDNA is well suited to the development of novel pathogens; it will no longer be necessary to use naturally occurring pathogens in BW. For example, slight genetic alterations in bacteria which naturally occur in the human body (i.e., E. coli) could produce novel, deadly agents for BW. E. coli must be the best known of all bacteria, and methods for introducing foreign DNA into E. coli, and methods for mass-producing E. coli, are becoming highly refined. There are a great many viral pathogens which have not been developed for BW use to date. But molecular biology has made great advances in the understanding and manipulation of viruses in recent years, and it is likely that the new technologies will lead to the development of many new viral agents for BW. An advantage of viruses is the lack of successful vaccines and antibodies to defend against viral BW agents.

The new technologies will lend themselves to development of improved methods for dispersal of BW agents. The munitions for large-scale dispersal of antipersonnel agents which have proved most successful are bags and bomblets dropped from airplanes (for arthropod agents such as fleas), and aerosol and other liquid spray systems (for direct release of microorganisms designed to be inhaled).4 It is already possible to selectively breed new varieties of mosquitos, ticks, fleas, or other agents which are resistant to insecticides, and with the new biotechnologies it may soon be possible to engineer into such agents many other traits. RecDNA could be used to develop more hardy pathogens, designed for greater survivability in high-speed dispersal systems.

Finally, hybridoma technology could be used in the development of monoclonal antibodies to the biological and chemical weapons in the U.S. arsenal. These could be used in protection and treatment of personnel, and in improved detection kits. A reliable vaccine can make use of a pathogen possible, or be an effective weapon in itself. Such was the case in Vietnam in the mid 1960s, when an epidemic of plague was responsible for thousands of North Vietnamese deaths, but had no significant effect on U.S. troops, who received vaccines and regular boosters.5

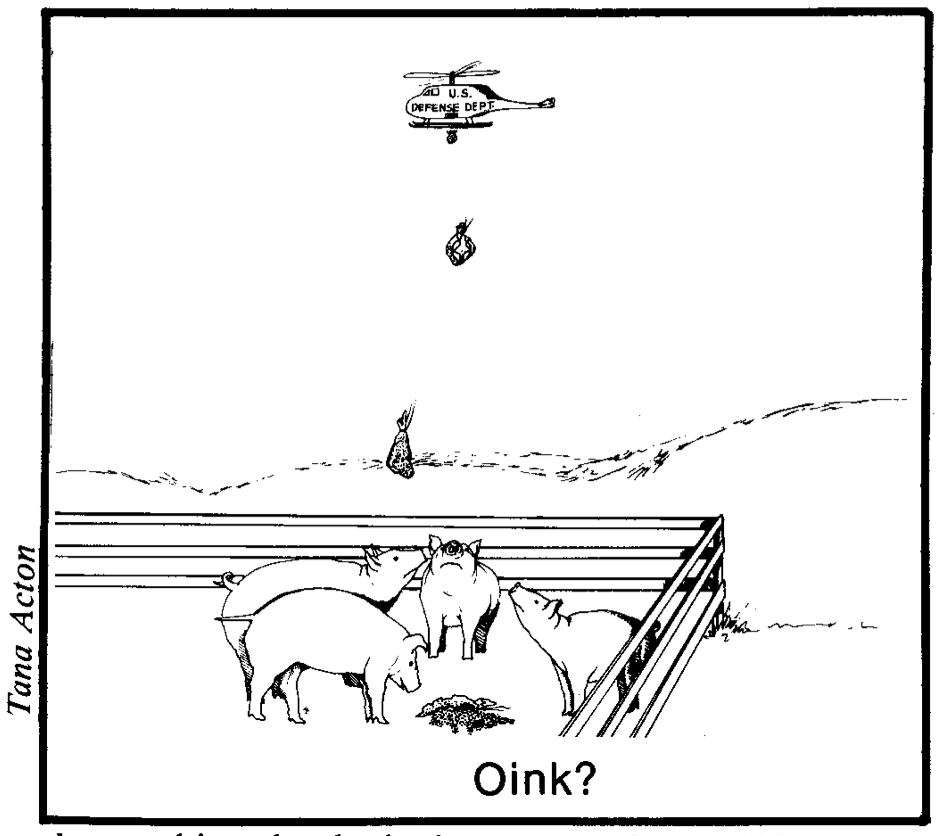

Many similar applications to antianimal agents are possible. BW directed at livestock can be especially damaging, because it can be used during “peacetime” to do damage to a country’s economy. For example, the 1979 swine virus epidemic which led to the destruction of one half million swine in Cuba was thought by many to have been started by the CIA.6 Whether these allegations can be proven or not, the epidemic could easily have been caused by BW, and illustrates the tremendous impact on a nation’s economy such antianimal agents may have. There are more than 125 known viral diseases which affect livestock, but vaccines exist for less than fifty of these. It is clear that opportunity exists for development of new viral BW agents for antianimal uses.

New anticrop agents can also be developed. Because many new varieties of crops are available to military researchers while under development at the U .S.-dominated International Agricultural Research Centers, new diseases and pests might be developed for new varieties before they are even introduced. One result of the adoption by both industrialized and Third World countries of the new “high yield varieties” of crops is a trend toward monocultures. Because of the increasing genetic uniformity in such crops, a single agent could be used to wipe out a larger proportion of the year’s harvest. RecDNA is suited to the manipulation of various pests of crops, especially the fungi. A variety of research has focused on fungi as agents for biocontrol of weed species, and this experience suggests that fungi are especially well suited for economical, large-scale destruction of a target species, whether a weed or a staple crop.7 It should be noted that crop destruction has always been a favorite tactic of the U.S. military.8

Antioil, Antimachine…

The new biotechnologies could also be used to develop completely new classes of biological agents. One such agent is suggested by a recently developed microorganism for which General Electric received a patent in a controversial Supreme Court decision.9 This new bacterium contains a combination of plasmids from several bacteria with abilities to eat different hydrocarbons, and it is purportedly capable of degrading all the important hydrocarbons in oil. Its targeted application is cleaning up oil spills, but it or similar organisms might also be used for destruction of oil reserves.

While it sounds a bit far fetched to imagine the Department of Defense developing microorganisms capable of debilitating military equipment of other countries, such agents may in fact be conceivable. For example, the Office of Naval Research has assembled a group of scientists to look into applications of recDNA in the control of slime molds which fowl the bottom of ships, reducing their speed and fuel economy.10 If recDNA can be used to protect U.S. naval ships against these microorganisms, it could also be used to increase their growth and persistence on the ships of other navies. Microorganisms could also be developed with an appetite for plastics or rubber, materials which play a central role in many kinds of military equipment.

Why Not the Best?

These examples illustrate how the new biotechnologies may, and no doubt will, be applied to BW research. It would be a strange day when the U.S. military failed to utilize new technologies as quickly as applications for them could be found. There is now reasonable evidence to indicate that a growing research program exists within the Department of Defense to apply recDNA and hybridoma technologies. Jonathan King, MIT biologist, is convinced that the military is exploring recDNA, and points to a request to the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee of the National Institutes of Health for permission to transfer the pneumococcus toxin gene to E. coli as an example of recDNA research with BW implications.11 Pneumococcus is responsible for pneumonia in humans.

THE NEW BIOTECHNOLOGIESRecombinant DNA (recDNA) technology consists of using various enzymes to insert foreign DNA into the genetic material of a living cell. It has been used to insert human genes which code for useful proteins into microorganisms such as E. coli (which lives in the human intestine). For example, human growth hormone and human insulin are now being produced by engineered E. coli for clinical use. While recDNA methods have been applied mainly to microoganisms, it is clear that genetic engineering of plants and animals will soon follow. These advances are being exploited by hundreds of new commercial laboratories in the U.S. alone, as well as many in Europe, Japan, Israel, and other countries. Commercial applications are being developed for agriculture, medicine, and the chemical and energy industries. Another important new technique is a process of fusing fast-growing, cancerous cells with antibody producing cells to make what are known as hybridoma cells. These can be grown in culture to produce monoclonal antibodies–pure highly specific antibodies–in large quantities. Advances in plant cell culture, fusion of cells to combine their DNA, and other new techniques, in combination with recDNA and hybridoma technology, have led to a revolution in biotechnology. It is now possible to manipulate the genes of many organisms in more controlled ways than ever before. It is also possible to store organisms as undifferentiated cells, then clone whole organisms as needed, or to engineer many new kinds of biological factories in which needed proteins are produced by fermentation. |

A recent advertisement which appeared in the “Positions Open” section of Science provides another clue.12 The ad starts, “The U.S. Army is seeking a Deputy Director for the Chemical Systems Laboratory, a major laboratory of the U.S Armament Research Command.” It goes on to say that, “Located on Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, approximately 20 miles east of Baltimore, Chemical Systems Laboratory conducts research and development activities for material related to chemical and biological defense and chemical deterrent. This area has recently received intense attention with the result of substantially increased programs, and support at all levels within the Department of Defense” (emphasis added).

The implication is that recDNA research already exists in the Department of Defense, as confirmed by the man who supervises all life sciences research for the Pentagon.13 According to this source, there is already a small program involving a half dozen recDNA projects and a larger number of hybridoma research projects, and this program is expected “to expand considerably in the next year or two.” Much of this expansion will take place at the Naval Biosciences Laboratory in Oakland, California (which is associated with the University of California, Berkeley). Further, beginning next year the Army, Navy, and Air Force will all “be in a position to consider proposals” for recDNA research.

While new developments in BW research have support at all levels within the Department of Defense, the State Department acts curiously naive as to the impact of recDNA on biological warfare. In 1981 a special Genetic Engineering Expert Panel was convened to advise the State Department on the strategic implications of genetic engineering. Among other topics, this panel of leading scientists discussed the “possible impact of genetic engineering in biological warfare against people,” and concluded that, “Genetic engineering will not yield pathogens that are any more lethal than some that already exist (e.g., anthrax). Essentially, genetic engineering is not required–Napoleon’s army was decimated by dysentery.”14 This view is apparently shared by those in charge of formulating guidelines for recDNA research at the National Institutes of Health as well. For example, Dr. Stanley Barban of the Office of Recombinant DNA Activities knows of only one Department of Defense recDNA project–developing a vaccine to Rift Valley Fever in collaboration with a “private concern”–and believes that recDNA will not be used in BW research. He also argues that existing pathogens are effective enough.

This attitude is dangerously misleading. The sooner it is recognized that the Department of Defense has already initiated a program to apply recDNA and other new biotechnologies to BW research and development, the sooner realistic steps can be taken to limit the development of new, more dangerous biological weapons. What can be done to increase awareness of this issue, and prevent further military research and development?

Antimilitary Agents

As a first step we must develop a better understanding of the army’s plans and current research activities. This might best be done through enlisting prominent politicians, journalists, scientists and activists in an effort to bring relevant information to the public. The second step is to examine the potential impact of new biological weapons on the future of this country and its foreign policy.

Now is the time to act, before the new biological weapons become as ubiquitous as nuclear weapons have become. Tactics used by Science for the People in the past might be a good place to start, such as demanding that these issues be debated in public, revealing military control of the research, and challenging the political-economic structure which supports it.

The next generation of biological weapons will affect everyone, but their development could easily remain secret until long after the new weapons become a permanent feature of armaments throughout the world.

>> Back to Vol. 14, No. 3 <<

References

- Hearings before the Subcommittee of Health and Scientific Research of the Committee on Human Resources of the U.S. Senate, 95th Congress, March 8 and May 23, 1977.

- Robert Gomer, John W. Powell and Bert V.A. Roling, “Japan’s Biological Weapons: 1930-1945,” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 37 no. 8, 1981.

Maj. William A. Buckingham Jr., Operation Ranch Hand, The Air Force and Herbicides in Southeast Asia 1961-1971. Office of Air Force History. (Obtained by National Veterans Task Force on Agent Orange under the Freedom of Information Act.)

Nicholas Wade, “Biological Warfare Fears May Impede Last Goal of Smallpox Eradicators,” Science, vol. 201, July 28, 1978.

- A. Conadera, “Biological Weapons and Third World Targets,” Science for the People, vol. 13, no. 4, 1981, pp. 16-20.

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, The Problem of Chemical and Biological Warfare, vol. II. Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm, 1973.

- Seymour M. Hersh, Chemical and Biological Warfare: America’s Hidden Arsenal, Bobbs-Merrill, New York, 1968 (see pp. 186-187).

- Peter Winn, “After the Exodus: is the Cuban Revolution in Trouble?” The Nation, June 7, 1980.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Biological Agents for Pest Control: Status and Prospects, February 1978 (see pp. 43-45).

- Arthur H. Westing, “Crop Destruction as a Means of War,” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 37, no. 2, February 1981, pp. 38-42.

- Sheldon Krimsky, “Patents for Life Forms Sui Generis: Some New Questions for Science, Law and Society,” Recombinant DNA Technical Bulletin, vol. 4, no. I, 1981.

- Colonel Friday, Department of Defense (The Pentagon). Personal communication, telephone interview of August 6, 1981.

- Dr. Jonathan King, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Personal communication, telephone interview of March 12, 1982.

- Science, Nov. 20, 1981, p. 949.

- Dr. Phil Winter, Department of Defense (The Pentagon). Personal communication, telephone interview of March 12, 1982.

- Summary of meeting of Feb. 20, 1981, dated May 15, 1981, by Jean Mayer, Chairman, Ad Hoc Genetic Engineering Panel, and Member, Advisory Committee to the OES Bureau.