This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The Safety Factor: Tampons — Looking Beyond Toxic Shock

by Judith Beck & Charlotte Oram

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 5, September-October 1981, p. 12 — 18

Judith Beck and Charlotte Oram are researchers for Woman Health International.

She had been little more than a child—she had been healthy—now she was a statistic—one of many who died within days after the onset of an illness that could have been avoided. That’s the ultimate consequence. Then there are those who have lost fingers and toes. There are others whose vital organs have been affected, who will require years of medical treatment. They all had one thing in common: the onset of the syndrome was during a menstrual period.

If they had known the warning symptoms of toxic shock syndrome; if they had known that tampons were somehow involved, could all this have been avoided? Yes—according to the Center for Disease Control of the Public Health Service. By not using tampons, women can almost entirely eliminate their risk of contracting toxic-shock syndrome.

On October 20, 1980, the Food and Drug Administration proposed a regulation requiring warning labels on all tampon packages, and notices on shelves in the market place where tampons are sold. Unfortunately they have not made it mandatory. The voluntary efforts of the manufacturers in warning the public on the hazards of tampon use have proved to be haphazard at best. Some packages contain warnings—others do not. Their advertising continues as though the question of tampon safety had never been raised. It is business as usual.

Woman Health International (WHI) submit that the FDA’s regulatory power should be exercised beyond mere recommendation of warnings when there is a threat to life and limb, and should bypass protracted hearings when time is a vital factor.

Tampons Before Toxic Shock

In the late 1970’s, long before toxic-shock became an issue, WHI was troubled that so little was known about the ingredients of a product placed inside the body and used universally. We sought from the tampon manufacturers specific information on the fiber and chemical content of their product. Bland and reassuring replies devoid of specifics were received, along with the assertion of their “proprietary right” to withhold trade secrets. We asked the Food and Drug Administration to supply the basic information—but they cited their inability to breach the manufacturers’ proprietary rights.

We turned to the medical research community, requesting of medical schools in the United States and Canada the status of any research done on tampons. The negative response only confirmed that the tampon as a possible traumatizing agent for half the population had not been envisioned.

We contacted women’s organizations, nursing schools and nurse-midwifery schools all over the country to alert them to the sweeping significance of what had become by then the tampon problem—and urged them to highlight it in their publications and to pressure the Food and Drug Administration and House Subcommittee on Health and the Environment to take action requiring complete labeling of contents.

Our coverage of the extant medical literature on the subject resulted in a June 1980 report distributed and presented to the Food and Drug Administration OBGYN Advisory Panel meeting on October 10, 1980. The report was titled “Forty-seven Years Later—Are Tampons Really Safe?”

What our research revealed—and what is never referred to in industry advertising—were warnings about possible adverse reactions. In 1938, doctors conducting the first absorbency test warned of possible damage due to irritation by a foreign body in the vagina.1 In 1942, Dr. Barton, in the British Medical Journal, cautioned that cervicitis and vaginitis might occur as a result of local irritation from impurities or chemicals, and that infection of the genital passage could be caused by bacteria carried into the vulva on the applicator.2

In 1943, Singleton and Vanorden objected that tampons had been put on the market without the usual laboratory and animal experimentation.3 In the same journal, Dr. A.A. Taft pointed out that vaginal tampons provide warmth and moisture, which are the necessary factors for germination of spores and fungi. Dr. Taft had learned from manufacturers that tampons were not sterilized, since that would impede absorption, but depend on chemical treatment to eliminate the organisms present in raw cotton.4

The Chemical Factor

It’s been taken for granted much too long that the vaginal tract is relatively impervious to chemicals. Spermacides and douches have been used that contain mercury, radium and boric acid, all toxic substances that can be absorbed by the body and can cause birth defects. There were warnings as far back as 1918 when Dr. David Macht wrote an article entitled “Absorption of Drugs and Poisons Through the Vagina.”5 The article described in detail his experiments with dogs and offered convincing evidence that the vagina was capable of absorbing toxins, with misery and even death as a result. Nobody listened. Animal studies were not considered accurate enough to determine standards.

On January 19, 1981, the Council on Environmental Quality published a report entitled “Chemical Hazards to Human Reproduction” which postulated that animals are a much more accurate indicator of real human hazards—at least as far as reproduction is concerned—than scientists have generally believed. Chemicals which are known from other evidence to be hazardous to human reproduction were used in laboratory animals. A strong similarity was found not only in the way the chemicals produce damage, but also in the doses that cause the damage. The report urges more research, pointing out that fewer than 5% of the 55,000 chemical substances in commercial production in the United States have been tested for their effect on reproduction.

The December 12, 1980 issues of the Journal of the American Medical Association published an article on “Vaginal Absorption of Povidine-iodine,” in which the author warned that the “vagina is a highly absorptive organ” and this commonly used vaginal disinfectant can produce an overload of iodine which can affect the thyroid and is particularly dangerous to the fetus.6

Through research on patent applications of the 1970’s, we found that manufacturers were apparently using substances such as acetic acid, polyvinyl alcohol, ethers, methylcellulose and phenol, among other chemicals. We found that phenol (a coal-tar derivative) and acetic acid are listed by the Toxic Substances Control Sourcebook as possible toxic substances.

There is evidence in the medical literature of terrible consequences to animals injected with polyvinyl alcohol – and methylcellulose. When Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) erupted, it was suggested that carboxymethylcellulose, used in “Rely” and other superabsorbent tampons, might well be the factor linked to TSS.

While TSS is a rare disease, there are many other illnesses affecting women which might be due to chemicals and polymers in tampons.

Our alarm concerning tampon safety was reinforced from another quarter. Complaints from consumers, doctors, and other health professionals in 1979-80 to the FDA’s Device Experience Network (DEN) revealed that tampons, regardless of brand, produce mucosal alterations in the vaginal area, drying, microulcers (very small ulcers), hemorrhaging and dermatitis. The following is a sample of comments:

1) Dr. states that in last 2 years he has treated more cases of vaginal ulcerations…These are about 1 inch in diameter…and bleed on contact and in every case have been associated with the use of medicated tampons. [Playtex deodorant]

2) Have seen 5 patients with very serious vaginal ulcers related to use of this product. [Playtex] Have notified manufacturer who said they would have their medical director get in touch, but have received no further response.

3) Complainant’s physician attributes use of Tampax’s new “Slender Tampon” to having caused a vaginal ulcer….Four other patients developed abrasive ulcers while using the same product. Problem…is that it is so compressed, the tip is extremely hard and rough, causing abrasion.

4) Consumer originally purchased these (superplus) tampons because they are more absorbent. [Tampax] Since she has started using them she noticed her period increased from 4 days to 5½ days…during the second month of use, she noticed that her period increased from 5½ to 7 days and she has been using more of the product. She also experienced irritation and spotting in the vaginal area.

It passes all understanding that the safety of this medical device—the tampon—escaped serious attention not only from practicing physicians but also from manufacturers and government regulators alike, when so vital an area as the birth canal was involved.

What Is Toxic Shock Syndrome?Although the medical community was alerted to toxic-shock syndrome in 1978, it was not until May of 1980 that the high occurrence of TSS among menstruating women was made public. Toxic-shock syndrome occurs mainly in women under 30 years of age; one-third of all cases are women 15 to 19 years old. However, TSS has stricken females from 6 to 61 years old. Although toxic-shock syndrome has occurred in men, 99% of cases occur in women, and 99% of these women had onset of TSS during a menstrual period. Studies have shown that TSS occurs in 6 to 15 per 100,000 menstruating women. In June 1980 a report was published linking toxic-shock syndrome to tampons. One brand of tampon, in particular, was associated with toxic-shock syndrome—Rely, which was subsequently withdrawn from the market. However, no brand of tampon is without risk of inducing TSS. Use of sea sponges as menstrual devices does not appear any less likely to induce TSS than use of tampons. The symptoms of toxic-shock syndrome, all present with the disease, are (1) sudden onset of high fever, usually over 104°, (2) vomiting and diarrhea, (3) rapid drop in blood pressure (below 90 systolic for adults), (4) sunburn-like rash which later peels off in scales, especially on palms and soles. The acute phase lasts 4 to 5 days, and convalescence takes one to two weeks. About 10% of reported cases have been fatal. Most TSS deaths occur within a week of onset of the disease. Toxic-shock syndrome is now believed to be caused by the Staphylococcus aureum bacterium, which enters the body through a wound. In cases of TSS in menstruating women, use of tampons apparently causes or facilitates entry of S. aureum through the vagina. The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) acknowledges that “Tampons play a contributing role in the development of TSS, but do not cause the syndrome.” Toxic-shock victims may be treated in the acute phase by hospitalization in intensive-care units, where they are given intravenous fluids and medications to raise blood pressure. Some doctors use certain antibiotics after ascertainment of the disease by bacterial cultures. It has not, however, been proven that antibiotics cure the disease or even improve the outcome, although they do appear to prevent its recurrence. The CDC does not recommend that women without symptoms be routinely cultured for S. aureum. Women can almost entirely eliminate risk of toxic-shock by not using tampons. Risk can be reduced by using tampons only intermittently, that is by using an alternative device for part of the menstrual period. If a woman develops a high fever or vomiting and diarrhea while using tampons during her period, she should discontinue tampon use and seek immediate medical attention. Source: Center for Disease Control, Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, January 30, 1981. |

New Questions—New Research

A study by Drs. Friedrich and Siegesmund, reported in The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of February, 1980, supported by a grant from the Kimberly-Clark Corporation, is revealing of the complications inherent in evaluating industry-supported research.7

The summary of the report, entitled “Tampon-Associated Vaginal Ulcerations,” says that through the use of colposcopic examination (examination using a magnifying instrument) it was found that tampons produced changes in the vagina such as drying of the mucosa, epithelial layering and microulcerations, usually of a temporary nature. The authors concluded:

Tampon products containing superabsorbents are significantly more likely to produce microulcerations than are conventional tampons when worn at times other than during active menstruation. Chronic production of these alterations could lead to clinically obvious lesions of the vagina, and should now be considered in the…diagnosis of vaginal ulcers.

Drs. Friedrich and Siegesmund are quite proper to extol the technique of colposcopy to detect injuries obscured to the naked eye. They may be correct in concluding that many of these lesions are temporary—although their experimentation did not extend beyond two cycles of menses. But what of the danger of spread of infection present during the transitional healing process? What of the effects of a protracted series of ulcerations over years or even decades? What of concern for the legions of women who do not have the benefit of refined techniques of vaginal examination? Is it any wonder that literature available to the public gives rise to more questions than answers?

These were some of the questions Woman Health International put to the Food and Drug Administration OB-GYN Advisory Panel at a meeting on October 10, 1980, called for the purpose of exploring toxic-shock syndrome and the tampon connection. At the same meeting, an expert witness, Dr. Douglas Barns of the Mary Bassett Hospital, Cooperstown, New York, described the appearance of gross vaginal ulcers in patients. Other experts testified in the same vein. In all cases, the patients used tampons.

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) follow-up on Toxic-Shock Syndrome, September 19, 1980, dramatically established one brand, ”Rely,” as statistically at high risk (71%) in association with TSS. Other tampon brands were involved in 28% of the cases. The CDC suggests a possibility that tampons are associated with TSS because they serve as a proxy for some as yet uncharacterized risk factor. In the same publication CDC states that studies suggest tampons play a contributing role by traumatizing the vaginal mucosa and thus facilitating local infection with staphylococcus aureus and absorption of toxin from the vagina.

An observation, frightening in scope, springs from the mere mention of the “proxy” role of the tampon in toxic-shock syndrome. If TSS, why not other diseases which might result from bacteria entering the bloodstream through tampon-induced lacerations in the vagina?

In the American Heart Association’s descriptive pamphlet on how Bacterial Endocarditis strikes persons with structural abnormalities of the heart or great vessels, the American Heart Association recommends a regimen of antibiotic treatment for patients with these defects who are about to be exposed to potential sources of bacterial seeding. The regimen is prescribed for even such simple procedures as having one’s teeth cleaned by the dentist. Mucosa of the month is much like mucosa of the vagina. Has the bacterial endocarditis-prone woman been warned of possible complications from the use of tampons?

An article on neonatal infections by Giuseppi A. Botta of the University of Genova in September, 1979,8states that adhesions of group B streptococci to the human vagina have been recognized as the causative agent of serious neonatal infections. Can group B streptococci remain adherent to vaginal epithelial cells or adhesions over a long period of time, thereby exposing the newborn to B streptococci during the delivery process? Dr. Botta says ‘yes.’ “Once it is established, the carrier condition can persist for a long time (months or years) and obviously during pregnancy.”9Shouldn’t we raise the question of possible tampon origin?

We note, also, failures of the tampon industry, itself, to responsibly inform the public about limitations or hazards to their product. We quote from the educational pamphlets of two companies: “Menstrual odor is formed outside the body when the flow comes in contact with air” and “You can avoid menstrual ordor entirely when you wear a tampon. Because it is worn internally where no air is present-no odor can form at all.” Why, then, are deodorants added to tampons? Why introduce one more foreign substance inside the body? What of the superabsorbent tampon? The earlier cited industry-supported Friedrich/Siegesmund study mentions that tampon products containing superabsorbents are significantly more likely to produce microulcerations than are conventional tampons. Yet, superabsorbents are promoted by the manufacturers as the answer to every woman’s prayer.

Who knows how many illnesses or diseases in the past forty-eight years may have been related to tampon-induced abrasions and lacerations?

| Glossary of Medical Terms

1. Bacterial endocarditis—inflammation of the lining of the heart and its valves produced by bacterial infection 2. Cervicitis—inflammation of the cervix 3. Colposcope—an instrument designed to facilitate visual inspection of the vagina 4. Mucosal—pertaining to the mucous membrane which lines the cavities and passages of the body communicating directly or indirectly to the exterior 5. Neonatal—relating to or affecting the newborn during the first month after birth 6. Staphylococcus—a genus of bacteria that generally appear as parasites on skin and mucous membranes (staphylococcus aureus is a member of the family) 7. Vaginitis—inflammation of the vagina—there are several forms |

Other Countries—Other Procedures

Other countries have reported instances of toxic-shock syndrome—Canada among them. The government there was quick to act. As of December 1, 1980, manufacturers are required to have warning labels on the outside of all packages sold and to include an information package insert.10

Japan, on the other hand, reports that they have had no cases of toxic-shock syndrome. It is worth noting that in Japan standards for commercial tampons have been in force since at least 1969,11 and the National Institute of Hygiene regularly subjects these articles to rigorous tests. In Japan no superabsorbent or deodorant tampons are permitted and they do sterilize tampons with ethylene oxide gas (EOG). This practice was stopped in the United Stated for reasons which are not clear, since EOG is still in use for other medical products and as a fumigant for foods. Note, in this connection, that in the United States, tampons are designated by the United States Pharmacopeia as a “non-sterile pharmaceutical product,” requiring “special treatment” to render them microbiologically acceptable for use.12

The FDA and Regulation

Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley, a physician and chemist, is acknowledged as the individual most responsible for the development of the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Wiley espoused the principle that the right of the consumer was the first thing to be considered. He felt that the bureau’s job with respect to industry was one of enforcement rather than persuasion. In 1912, five years after he became head of the newly-formed agency, he resigned in bitter protest after political pressure had blocked his efforts at regulation.13

In 1974, forty years after tampons had been on the market, the FDA started monitoring their manufacture. We found a doctrine called “the history of safe use” was in operation at the FDA. Simply stated, this means that if a product has been on the market a long time, with no known adverse effect, it is considered safe.

Warnings in the medical literature concerning tampons (we have quoted only a few) had been steadfastly ignored. Possibly of greater significance, there has been a dearth of adequate testing. From 1938 (when 95 women participated in a study to determine the absorbency effectiveness of the then new product)14 to 1967 (when 187 women in Bath, England were examined for possible alterations of the vagina due to tampon use)15, the reports revealed that less than two thousand women were actually examined to determine possible damaging effects. This is a far cry from the criterion suggested by Dr. Robert Wheatley in 1965 who declared:

We hasten to point out that in order to obtain significant statistics regarding an uncommon lesion [injury] it would be necessary to analyze thousands of cases.16

In 1978 the FDA proposed that tampons be classified as a Class II medical device. It was not until February 1980 that the final regulation went into effect. To understand the complexity of medical device categories, let us briefly define them:

Class I: General Controls. Products subject only to general controls, such as registration of manufacturers, recordkeeping, etc. Examples: tongue depressors, arm slings.

Class II: Performance Standards: Devices for which enough information exists to establish a standard are required to meet performance standards for components, labeling, etc. Examples: hard contact lenses, tampons.

Class III: Premarket Approval. All implanted and life-supporting or life-sustaining devices are required to have FDA approval for safety and effectiveness before they can be marketed (premarket approval can be required of other devices if general controls are insufficient and information is lacking to establish a performance standard). Examples: heart pacemakers, contraceptive devices.17

Unfortunately there is a loophole in the law that is over-used and abused, particularly in the case of Class II, the category designated for tampons. It is called “the Grandfather Clause.” It allows for small changes of a device without review or testing. By spacing minor changes over a period of time, the manufacturers have been able to make substantial changes in tampons without challenge. “Rely” is a case in point. Although “Rely” was the most radically changed tampon, other manufacturers followed suit.

Given the history of tampons to date, Class II is hardly an adequate classification. Since premarket testing is essential if there is ever to be a safe tampon, the tampon should become subject to the controls of Class III. The tampon already meets the criteria of Class III: (a) it is used internally; (b) it has been linked to a very serious disease; and (c) it has been shown to cause trauma to the vaginal area.

| FDA-Proposed Warning Label

“WARNING: Tampons have been associated with Toxic-Shock Syndrome, a rare disease that can be fatal. You can almost entirely avoid the risk of getting this disease by not using tampons. You can reduce the risk by using tampons on and off during your period. If you have a fever of 102° or more,and vomit or get diarrhea during your period, remove the tampon at once and see a doctor right away.” |

Politics of the Tampon Industry

The giant tampon industry evolved from a small beginning. In 1933 Dr. Earl Haas, a Denver physician, patented a cotton device which he called a tampon—to be worn internally to absorb the menstrual flow. According to Dr. Haas it was designed to absorb the fluid, not to block the flow. He sold the rights to a company called Tampax, Inc. Tampax became a multimillion dollar industry with its one product-tampons. According to Forbes, May 29, 1978, Tampax is one of the most profitable companies in American industry.

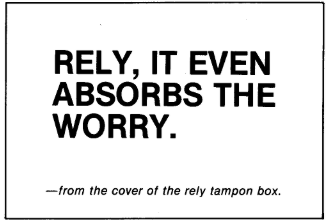

When companies like Johnson & Johnson (O.B.), Esmark (Playtex), Kimberly-Clark (Kotex), Purex (Pursettes) and then Procter & Gamble with “Rely,” entered the market, the competition became fierce. Millions of dollars were spent in promotion and advertising to capture the market. The vast sums spent for research were for a bigger and better tampon—not a safer or a sterile one. Absorbency became the by-word. Procter & Gamble was so proud of “Rely,” it advertised it “even absorbed the worry.” Now that “Rely” has been taken off the market, Procter & Gamble is spending millions of dollars in research to vindicate its product and to discredit the Federal Center for Disease Control findings. It is now estimated that the tampon industry has reached the one billion dollar a year mark in the United States and about the same overseas (Wall Street Journal, June 26, 1981).

There is much at stake here, but we feel that profit considerations should have no place in the equation. No one has been able to say that tampons, regardless of brand, are not related to Toxic-Shock Syndrome (TSS).

The Food and Drug Administration seems to be bowing to industry pressure, delaying again the mandating of TSS warning labels on and in tampon packages. The process to issue warnings, started by FDA in October of 1980 was at that time considered top priority. The subsequent delaying tactics are not surprising. With the stakes so high, with the administration openly bent on the scuttling of regulations, we can realistically assume that the outcome for timely labeling looks bleak.

Unfortunately, women are the pawns. The advertising directed at them does not focus on safety, and does not even allow them an informed choice. They are not told the contents of these products. They are not told the risks involved in their use. They are told that tampons are convenient, comfortable, and do not give away the “secret.”

Fifty Million Women Can’t Be Wronged

If women are to become a force for change, they must make their demands known. A grass-roots write-in campaign should be directed to the Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, to the manufacturers and to elected officials.

The address for the FDA is: Dr. Arthur Hull Hayes, 5600 fishers Lane, Rockville, MD. 20857.

Woman Health International recommends the following:

-

- Labeling, to include

- Fibers—type and grade

- Additives—to both tampon and inserter; used for any purpose including fragrance box, with circling of the particular size carried within

- Warnings and Cautions—in layperson language

- Medical Contraindictions—prominent placement in or on box

- Product Alteration—immediate removal of superabsorbent additives, deodorants or any known toxic substance

- Research Program—independent research, supported by government funding, to accompany industry research, both dedicated to produce a safe effective tampon or substitute device; parallel investigation of the synergistic long term effects of exposure to chemicals and fibers used in tampons and hygiene products for the past forty-seven years

- Monitoring—spot checks and inspections of worker health, materials quality and production practices of manufacturing plants to be done more frequently than the two-year random inspections now authorized by FDA

- Ethics—prohibition of sale for export of substandard or unlabeled tampon products

- Labeling, to include

Woman Health InternationalWe are a volunteer, non-funded organization with a fluid membership. Our primary concerns are with health issues that affect women. To that end we devote our time to research and to disseminating our findings with the hope of bringing about change where change is necessary. Where threats to health are evident we seek redress from government, industry and the medical profession. WHI has distributed information here and abroad to interested organizations, to lawyers who request it, to the press, to students, to scientific magazines, to medical researchers, legislators and regulatory agencies. |

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 5 <<

REFERENCES

- Arnold and Hagele. “Vaginal Tamponage for Catamenial Sanitary Protection.” Journal of the American Medical Association 110 (March, 1938): 790

- Barton. “’Review of the Sanitary Appliance with a Discussion on Intravaginal Packs.” British Medical Journal 1 (1942): 524.

- Singleton and Vanorden. “Vaginal Tampons in Menstrual Hygiene.” Western Journal of Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology 51 (1943): 146.

- Taft. “Concerning the Nature of Intracellular Inclusions and their Significance in Gynecology.” Ibid. :343.

- Macht. “Absorption of Drugs and Poisons Through the Vagina.” Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapy 10 (1918):509.

- Vorherr, et al. “Vaginal Absorption of Povidine-Iodine.” Journal of the American Medical Association 144 (1980):2628.

- Friedrich and Siegesmund. “Tampon Associated Vaginal Ulcerations.” Obstetrics and Gynecology 55 (198):149.

- Botta. “Hormonal and Type-Dependent Adhesion of Group B Streptococci to Human Vaginal Cells.” Infections and Immunology. 35 (1979):1084.

- Letter from Dr. Botta to Woman Health International, Dec. 5, 1980.

- Center for Disease Control. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Jan. 30, 1981.

- Into, et al. , “On Standardization of Commercial Tampons,” Bulletin of the National Institute of Hygiene. Tokyo, Japan, 87 (1969):74.

- United States Pharmacopeia XIX, General Information/ Nomenclature, p. 695.

- United States Pharmacopeia XIX, General Information/ Nomenclature, p. 695.

- United States Pharmacopeia XIX, General Information/ Nomenclature, p. 695.

- Morris. “‘Normal’ Vaginal Microbiology of Women of Childbearing Age in Relation to Use of Oral Contraceptives and Vaginal Tampons.” Journal of Clinical Pathology 120 (1967):636.

- Wheatley, et al. “Tampons in Menstrual Hygiene.” Journal of the American Medical Association 192 (1965):697.

- Requirements of Laws and Regulations Enforced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HEW Publication No. (FDA) 79-1042.