This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Women’s Health Book Collective: Women Empowering Women

by Barbara Beckwith

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 5, September-October 1981, p. 19 — 22

Barbara Beckwith is a former member of Science for the People. She is currently doing freelance work for feminist and political publications in the Boston area.

This article was compiled with permission from the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, from articles in Heresies, New Roots, New Age, plus interviews of members and excerpts from letters in the Health Book Collective’s files.

Much of the struggle for social and political change is necessarily a stuggle against—against sexism, racism, technological abuse, imperialism. But it is also a struggle for. We can sustain ourselves by looking at examples of groups who have succeeded in making positive change despite reactionary forces, internal problems, and backlash.

The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, authors of the book Our Bodies, Ourselves, is just such a model. The collective has, in the last ten years, helped to radically change the consciousness of women of all classes about their bodies and their health, and has empowered women to take action for their health in many ways.

Birth and Growth

The seeding event which eventually grew into the collective was a discussion group on “Women and their Bodies” at a Women’s Liberation Conference at Emmanuel College in Boston twelve years ago (1969). The group continued meeting after the conference. Their goal as to write a reference list of “good doctors” to distribute to other women. However, after talking and comparing experiences, they found that no such list could be compiled. Instead, they could only share stories of doctors handing out birth control pills without mentioning side effects, inducing labor simply to make the timing of birth more convenient to them, and dealing with women patients with condescension and judgmental insensitivity. “Dear, don’t worry” was the ordinary reaction of doctors to women’s questions about their bodies or medication.

It would be ten years before the reasons for such demeaning behavior by doctors toward women would be documented in such books as Ehrenreich & English’s For Her Own Good, Shapiro’s Getting Doctored and Ruzek’s The Women’s Health Movement: Feminist Alternatives to Medical Control. These books would trace the clinical practices, medical shop talk, medical texts and prescription drug advertising which together perpetrate the image of women as neurotic, indulging in psychosomatic ailments, and needing psychoactive drugs instead of medical information and treatment.

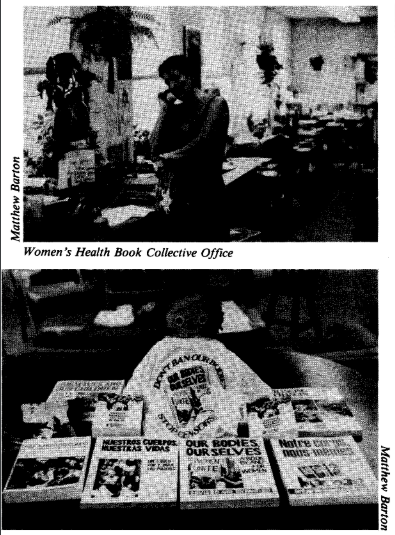

The Boston Women’s Health Book CollectiveThe Boston Women’s Health Book Collective’s office is at 465 Mt. Auburn Street, Watertown, MA 02172. Their health information files are available for use by teachers, students of all ages, journalists, nurses, physicians, midwives, consumer advocates and individuals with specific concerns. They also produce a quarterly health packet of newspaper clippings, copies of scientific reports, and listings of new resources. The packet is sent to 700 different health groups in the U.S. and abroad. A third edition of Nuestros Cuerpos, Nuestras Vida (the spanish version of Our Bodies, Ourselves) is now being printed. 30,000 copies of the book have already been distributed. New Our Bodies, Ourselves t-shirts with slogans, “Don’t Ban Our Bodies and Stop Censorship” encircling a picture of the books are available. All sizes for $7 (regular), $8 (french cut). Write, BWHBC, Box 192, West Somerville, MA 02144. |

Since these books had not been published in 1969, the women’s health discussion group decided to find out what they wanted to know about their bodies for themselves, by themselves. Each took a topic such as birth control, natural childbirth, masturbation, VD, abortion, post-partum depression or rape. They went to other women, they talked to nurses and doctors. They did research in medical texts and journals, where vital information is ordinarily kept inaccessible to the public. None had expertise in doing research or experience in any health-related field. However, they did trust they could find reliable information and learn the necessary research skills as they went.

Each women shared what she had learned in discussion with the rest of the group. From the very beginning, personal experience was integral to their analysis, as it enabled them to develop a critique of the information and health care they were getting.

The women were committed from the start to sharing whatever they learned with as many people as possible. They began a series of informal evening courses for friends and their friends. Instead of the traditional presentation-comments-questions style of teaching, they developed a more interactive format which allowed everyone to speak up and be heard. By using discussion rather than lecture, they as leaders gained new information and insights each time they gave the course. To expand the network of information further, they encouraged anyone taking the course to start a new group, using mimeographed copies of the material.

By 1971, those few women in the group who had family money (half the group was of working class or lower middle class background and did not have money) together put up $1,000 for a newsprint publication of their papers by the New England Free Press, for sale around the Boston area for 75¢. Within two years, 250,000 copies of “Women and their Bodies” had been sold. Not a cent had been spent on advertising. Royalties from this publication allowed them to reprint this book to sell at 30¢.

For the first two years, the group fluctuated in size, then solidified into a committed group of twelve women who wanted to expand and develop their core writings into a book. They incorporated as a collective of twelve; ten years later eleven of those women are still members, and the twelfth has moved to California to start a new group. Three books have been written by different combinations of collective members: Our Bodies, Ourselves, Ourselves and Our Children, and Changing Bodies, Changing Lives, a recently published book about sex and relationships for teenagers. All three use the format of factual information interwoven with extensive quotations from personal interviews and discussion groups. Women, men, and children from all over the country share their varied but frank feelings and experiences. The result is a set of books which validate individual feeling and experience as an important source of information and which support the right of people to information which experts usually monopolize.

In retrospect, the Collective’s decision to publish with a commercial publisher in order to reach as many women as possible seems a logical one. However, it took the group eight months of discussion to reach consensus on this decision because of concerns about publishing with a profit-making capitalist company. The agreement that they did reach with Simon and Schuster was unprecedented. The Collective insisted upon and won the right to retain the copyright themselves, to set a ceiling on the book’s price, and to keep control of the layout, advertising and editorial decisions. Most importantly they won a 75% discount for clinics and other nonprofit health organizations. The book has now sold over 2,000,000 copies. At present, the Collective is “networking” the book internationally by arranging with publishers to give women’s groups in different countries complete control over translation and editing.

With the royalties, the Collective supports a variety of women’s health projects. They contributed $15,000 to start Healthright Newsletter. The Collective helped produce the film “Taking Our Bodies Back,” gave money to the Wounded Knee Health Collective, and cosponsored the 1975 Boston Conference on Women in Health. In addition, they co-produced health information booklets with a group in Cuernavaca, Mexico, as well as the first edition of the International Women and Health Resource Guide.

They were also able to start paying themselves for the work they were doing, which until then had been voluntary labor. In 1973, one woman was paid to be coordinator. By 1977, all members were paid hourly for the work that they did for the Collective. As one member commented,

We couldn’t do now (volunteer our labor) what we did then. It now takes two to support a family, or two jobs for a woman head of a household. Since we are women, we are all one class that is economically discriminated against.

Internal Processes

In order to last 11 years, a group needs remarkable solidarity and commitment from its members. While Our Bodies, Ourselves has made them financially able to support themselves, the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective continues because members have committed themselves to a life-long process of working together. They have not ignored but have worked through internal problems which are similar to those of every group.

The Collective has been remarkably open about such group dynamics. In an extensive article in Heresies magazine, they have written about their “Working Together, Growing Together”:

Learning to function as a nonhierarchical group presented us with some painful issues involving power. In the political groups run by men where many of us had been active, we had seen how all women and less powerful men had very little to say in what went on. In not wanting to repeat that misuse of power, we took on an unspoken ideal of leaderlessness, which just brushed power conflicts underneath. We have learned that every group has leaders; the important thing is how they lead.

One woman in the group was particularly active in the first publishing project and in fact did many hours of work singlehandedly. The group needed her energy and perserverance for the book to come out well. Yet over the months she held an increasing influence in all aspects of their work without consciously intending to.

Because of her engaging personality and assertiveness she became the consistently dominant figure in the group. She was, for instance, better able than anyone else to sway the group’s decisions or to come in after a decision had been made and turn it around.

Tensions arose, but it was a long time before they were expressed and then they took the form of intense individual conflicts. But it was really a whole group issue.

Our self-doubts and feelings of inadequacy made us give her more power than she perhaps even wanted. Finally all of us were able to talk about our anger toward her and why we tended to invest her with power. Our support for her to leave her big sister role came as much from our caring for her as it did from our need to be free of her domination.

Gradually, a stronger sense of self-respect and equality has developed among members. As they emerged from that struggle with their group intact and their friendships deepened, they realized that power can be sharing, that there can be power without dominance.

Another part of the group’s strength is their closeness to each other through 11 years of personal as well as political sharing. Their inner connectedness has grown steadily as they look after each other’s children, have family picnics, play music together, meet for meals and spend long hours in searching conversation. They have seen each other through five new babies, some dramatic affairs, a wedding, three divorces, one case of hot flashes, four parents’ deaths and the illnesses of several others, one child going off to college and eight entering adolescence, and some crucial professional decisions.

The Years Ahead

The impact of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective cannot be measured in specific gains or accomplishments. In interviews, they steadfastly refuse to take special credit for changes in health care across the country. They maintain that what progress has been made is because of the continuing effort of vast numbers of women. This entire network has made gains in restoring the practice of midwifery, in home birthings and home-style hospital birthings, and in women’s increased awareness of the hazards of various contraceptives. Our Bodies, Ourselves may have helped raise women’s consciousness originally, but now it is all those women (individually and collectively) speaking up for their rights who have won changes. The Collective’s part of that network is a commitment to disseminating as much health information to as many individuals and groups as possible.

Still, the monolithic medical establishment remains entrenched in America. Therefore, a vast amount of the work the Collective must do is a stuggle against as well as for. The struggle continues to get the Dalkon Shield (a type of IUD) removed from the market, alert women to the hazards of estrogen therapy during menopause, publicize and take action against the extent of sterilization abuse, reverse the rising caesarian birth rate and the continued induction of labor for non-medical reasons. In addition, the Collective must now fight Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority’s backlash against Our Bodies, Ourselves, which the Moral Majority calls “pornographic sex education.” In Belfast, Maine, the case to keep the book on high school library shelves won. But in Milwaukee, only students with parents’ signed permission may read the book. The Collective welcomes support in letters to congresspeople about book-banning, especially from groups who have found the book useful. Information about towns where the issue has been brought up is also sought by the Collective.

Despite these ongoing struggles, the Collective receives support daily from women in an ever-widening national and international network. A Chilean health worker writes about the Spanish edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves:

It was probably the first time these women have seen a book especially written by and for women. The pictures themselves were of great impact, and a positive one. Two women took upon themselves the task of organizing some reading sessions (many of the women do not read or can read very little) where the different themes could be discussed.

Another health worker from Honduras wrote:

People here, men and women, are almost completely uneducated about the body and its functions, but, once past the giggles, are eager to learn. I haven’t seen the book since it arrived. It’s been passed from co-worker to co-worker and each has invariably read the information on birth control and come to work whispering “Is that true?” while handing the book on to the next person. If I could give some copies to other health and nutrition workers, both the workers and the women’s groups they deal with would benefit.

The long-range impact of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective and Our Bodies, Ourselves is enormous. The book alone has given women legitimacy by giving them a voice, by creating a language for them to speak about their reality. As Belita Cowan of the National Women’s Health Network wrote:

OBOS has touched the life of every woman in the country, whether she realizes it or not. It changed our thinking so that we could regard birth as a normal function, not as a disease. It allowed a national network of groups to develop. The knowledge in the book is very powerful. It gives women that sense of entitlement, that they have a right to know.

In an era of reaction, leftists can take heart from this group, who began as “non-experts,” trusting their own experience enough to determine what information made sense when held up to the experiences of their lives. The network of information they were part of starting has grown into a national and increasingly international consciousness of medical abuses, alternative forms of health care, and possible changes that can be made. There is still much to fight AGAINST, but there is also much that has been and can be fought FOR.

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 5 <<

REFERENCES

- Ruzek, Sheryl. The Women’s Health Movement. New York: Praeger (1979): 87.

- Ibid., p. 84.

- Ibid., p. 90.