This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Earth Day at Livermore is Like Brotherhood Week at Auschwitz

by Adrianne Aron

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 3, May-June 1981, p. 24 — 27

Adrianne Aron is a member of the East Bay chapter of SftP and lives in Berkeley.

| The Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, with a 1980 budget of $368 million and prospects of greater endowments by the Reagan administration, is operated by the University of California for the United States Department of Energy. One of only two national sites for the design of nuclear weapons, it consists of a one-mile-square complex of buildings, protected by an elaborate system of gates, guards and enclosures. In April, 1980, the California Department of Health revealed that malignant melanoma, a deadly form of skin cancer, strikes employees of the Lab five times more often than it strikes people in the surrounding area. Usually a rare disease, ranking about tenth in reported forms of cancer, melanoma was found to rank first in diagnosed malignancies among Lab employees. Although the epidemiological study was widely publicized, no mention of it could be found at the Visitors Center, the Lab’s lavish facility for providing science education to the public. The Lab’s monopoly on information emanating from the Visitors Center insured that only pro-nuclear/pro-weapon propaganda was available.

The U.C. Nuclear Weapons Labs Conversion Project, a citizens group, has been working since 1976 to sever the Lab’s connection to the University, convert the whole apparatus to peaceful endeavors, and inform Lab employees and the general public of the dangers presented by nuclear weapons. With a lawsuit instituted in 1980 the Project broke the Lab’s monopoly on information and won the right to place literature in the Visitors Center and to sponsor bimonthly events in the Center’s auditorium. A forthcoming issue of Science for the People features an article on the work of the Labs Conversion Project. |

Ever since Three Mile Island, which forced me to confront my previously unacknowledged anxieties about radiation, I have arranged little exercises for myself, to avoid lapsing back into denial — denial of the issue’s magnitude and importance, denial of the ways in which it was affecting my life, denial of the tricks I was using to avoid looking at it. As a psychologist I know the value of these little exercises, and as a resident of the San Francisco Bay Area it wasn’t hard to plan an afternoon trip to Lawrence Livermore Laboratory (LLL), where scientists not only design nuclear weapons, but lobby for their proliferation. If one was after reality, here was a choice spot.

Throughout the earthquakes, isotope leaks, and health studies that have given the little town of Livermore international reknown, Lab officials have insisted that the public has no reason to fear the radioactive materials created and stored there: they are safe from earthquakes, harmless when leaked, and not responsible for the elevated cancer rates among laboratory employees. When the press was led through the plutonium facility, reporters were advised that the scientific community does not share the lay public’s fear of radioactive substances. Lab scientists expose themselves and their families to these alleged dangers every day. Would they do that if the dangers were real? Certainly I wouldn’t. And that is what brought me to Livermore. I wanted to find out how these folks were calculating their risks and how, through the Lab’s information media, the public was being helped to make realistic calculations of its own.

The information media were expanded on the day of my visit, for in addition to the lavish Visitors Center, there was a temporary exhibit on the premises, established for the commemoration of Earth Day. As befitted an Earth Day exhibit, I saw a number of tables holding pictures, charts, microscopes, wind-run devices, and cages with small animals. Looking just past the fairground, though, to the barbed wire that encircles thick, windowless buildings which block the view of the green hills beyond, I noted that these fine exhibits, celebrating LLL’s scientific contributions toward a safer environment and a healthier life, seemed strangely incongruous. Was I mistaken, or was this the place where workers were dying of melanoma, plutonium was leaking out the smokestacks, and weapons were being designed that threaten to destroy the whole world? The guards and the forbidding buildings told me I was not mistaken, yet this whole outdoor display for Earth Day belied it: Lawrence Livermore Laboratory was depicted here as a friend of the earth, without so much as a slingshot in its pocket. Here in the backyard of the weapons laboratory there was no mention of war, and in clear view of the chimneys there was not a word about plutonium.

All the data I had previously examined supported the view that a discharge of toxic radioisotopes, whether from bombs, power plants or storage sites, is certain to lead to cancer, probably cancer epidemics. LLL scientists testifying to Congress in 1973 had admitted that “one pound of plutonium-239 represents the potential for some nine billion human lung cancer-doses. It presents a major carcinogenic hazard for more than the next thousand generations.” Given all that, I expected Earth Day to feature some reassuring information about safety improvements at the Lab, especially since a plutonium leak had been discovered just a week before. Seeing nothing of the kind, I remarked on the oversight to a scientist tending one of the tables. “Oh, plutonium,” she said with a big smile and a wave of the hand, “that’s just an alpha emitter; you can stop it with a piece of paper.”

What?

I knew what she meant: unlike gamma rays or x-rays, alpha radiation does not penetrate through the body. A piece of paper will stop it. So will the outer layer of human skin. But to parlay this into a cavalier dismissal of plutonium’s lethal capabilities seemed to me sheer madness, for I knew, as she must too, that an invisible, microscopic speck of the stuff, weighing as little as a millionth of a gram, was enough to kill either of us if the air blew it around that piece of paper and into our lungs. Lodged there, its bombardment of surrounding tissue would in time produce a malignant pulmonary tumor; if carried away by the blood, the insoluble particle would generate a cancer wherever it finally settled: in the lumph nodes, liver, spleen, adrenal glands or reproductive organs. This scientist was suggesting, though, that plutonium poses no threat … a curious idea. Then she went on to say something even more curious, something which hinted that the real problem with plutonium is not radiological contamination, but rather its unpopularity.

Commenting on the subject’s omission from the Earth Day exhibit, she pointed out that nobody likes radiation — as if low popularity ratings were sufficient reason to exclude a villain from the show. In my business excluding unhappy thoughts from consciousness is called denial, but here at Livermore I was trying to learn how people in the science business are thinking, and they seemed to be thinking in terms of box office receipts. Had I come to the laboratory, or the theater?

Nobody Likes Radiation

Applied to me, the scientist’s point was well taken. I don’t like radiation. At Livermore’s Earth Day, had the pictures of suffering firs, there to illustrate “Smog Effects on Individual Trees”, been instead pictures of Hiroshima victims, captioned “Radiation Effects on Individual Human Beings”, I would not have found that pleasant. Similarly, at the Visitors Center I could enjoy the recording that began, “Has your nose ever twitched from a strange smell? Have you ever inhaled a lung full of air that made you cough? These are examples of pollution …” It would not have been enjoyable to hear a talk on the devastating pollution resulting from a nuclear blast. And it is a comfort to see that when the nuclear villain does appear at the Lab, he is upstaged by good guys like Patriotism. This happens more than once in the propaganda film on LLL shown in the auditorium, but is particularly vivid when the detonation of a nuclear “device” is shown and we see the circular crater of its aftermath. As this image fades out, the circular shape of the Jefferson Memorial fades in. Had the camera turned to close-ups of cremated and blinded animals near the crater, the effect would certainly have been grotesque.

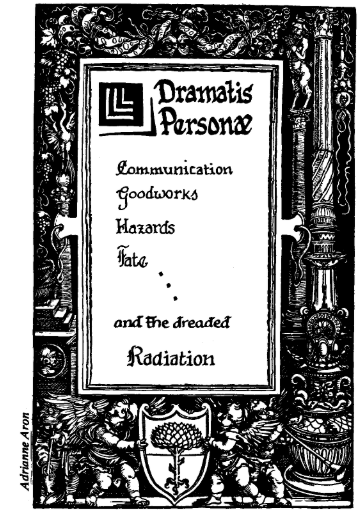

In this drama of modern life we are living, the part of the villian Radiation is always morbid, and it is not surprising that we should prefer having the spotlight shine on more upbeat things. The only surprise is that the Lab is providing the stage and directing the performance.

At Livermore there is no shortage of upbeat characters to distract attention away from the villian Radiation. But all of them, oddly, seem to have issued from a medieval morality play, as personified principles of righteousness, dazzling the spectator by vanquishing evil. The first to catch my attention, Communication, was featured in a back issue of LLL’s monthly magazine, Newsline, which I picked up at the Visitors Center. In an article on Three mile Island we learn that “Communication during the episode fell apart,” making it impossible for truth to win out, and “creating the false impression that a near catastrophe was narrowly averted.” “It is that impression,” the author concludes, “not the event itself, that was the disaster … ” This conclusion, it should be noted, is based on statements by Ernie Hill, who sits on the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), and who was evidently hoping that Communication, a popular scapegoat, would steal the show at Three Mile Island. But even I, with a long history of falling for tricks like that, found the performance embarrassing. Communication Breakdown just can’t upstage Core Meltdown, even when the NRC so orders it.

Another symbolic principle of righteousness I encountered was the character Goodworks, who dominated the scene of Earth Day. Thanks to the literature available at the Visitors Center I was able to learn that Goodworks, representing all the Lab’s research in the biomedical and environmental sciences, received only 5% of its $368 million 1980 budget. Considering that Goodworks is called upon to appear in every public performance the Lab stages, and usually does an excellent job of attracting attention away from the villain, I’d say she’s underpaid.

Hazards, a quick change artist, is a character who plays bit parts and is good at improvisations. Just when it seems inevitable that Radiation will slip into view, Hazards begins to speak. Under the direction of Bob Kelley, manager of the plutonium facility, Hazards performs as both Botulism, the pernicious toxin a million times deadlier than plutonium, and Arsenic, which remains lethal forever and lurks about in pesticides. Hazards is a leveler, giving equally scary countenances to all the bad guys, radioactive or not.

Wondering if this lack of discrimination among hazardous substances was justified, I asked Bay Area Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR) whether in their opinion radiological contaminants warranted special attention. Their answer led me to see the character Hazards as a very significant member of the cast, whose role is not only to distract but also to deceive.

Whereas most other poisons have antidotes, PSR points out, most radiological contamination does not. Most other poisons are relatively local, endangering mainly those who manufacture and use them, whereas radioisotopes can destroy and disfigure whole populations and contaminate entire land masses for hundreds of thousands of years. While most other poisons can be safely stored and controlled, radioactive materials are certain to get out of control because the only thing which keeps them safe are the containers in which they are housed: the 55 gallon waste storage drums with a life expectancy of twenty years, already leaking; the power plants built on earthquake faults; and the accident-proof facilities like Three Mile Island and Lawrence Livermore Laboratory.

Hazards, it seems, makes furtive appearances on the stage, aware that Truth is always gunning for him and if he sticks around he’ll be shot down. My last glimpse of him was when I called the Lab and asked Bob Kelley if he thought there might be some link between the plutonium in his facility and the high melanoma rate on the premises. “Oh no,” he said, “No, it’s probably going to be something like fluorescent lighting that’s responsible.”

The last and saddest anachronism in the LLL cast is called Fate. Versatile, Fate acts differently when playing your fate than when playing mine, taking into account our respective habits, ages, genetic makeups, pleasures, and so on. Fate’s task is to get us to believe that it’s something about us, rather than something about radioactive substances, which imperils our lives. If we are Lab employees who like to eat lunch outdoors, for example, perhaps we are bringing upon ourselves the fatal melanoma by imprudent overexposure to the ultraviolet rays of the sun. The scientist who was ready to fend off plutonium with a piece of paper told me,

Let’s face it, we live in a dangerous environment. The foods I eat are liable to kill me. If I lived in the desert I’d be exposed to cosmic rays. As a chemist, I’m in a profession with the highest incidence of lymphoma of any occupation. If I were a farmer I’d have skin cancer to worry about.

Plainly, she knew about Hazards. I was soon to learn, though, that she is influenced more by the role of Fate, for when I asked whether she goes for frequent examinations to monitor her health and her exposure to radiation, her answer was, “No, my real concern is my own genetic makeup; heart disease runs in my family, and that’s what I need to consider.”

This gentle, intelligent woman had begun with the expression, “Let’s face it.” But it seemed to me she wasn’t facing it at all. To face it, I thought, she would have to look squarely at the strong possibility of an accident at the Lab, and at the number of people who, regardless of their occupation or family history or personal habits, would perish in its wake. A mere speck of plutonium, once lodged in the body, begins to kill that body by hitting surrounding tissue with alpha radiation. The body might last twenty years, but 24,000 years from now that same speck of plutonium will still be around, and will still have 50% of its original potency. How long

will we be around, I wondered, if the nuclear industry and the weapons lobbyists of LLL have their way? Not long, I reckoned, unless our scientists throw away their paper plutonium guards and stop blaming their genes for their vulnerabilities to destruction.

I went to Livermore looking for some lessons in reality, and came away alarmed. Hoping to find the advocate’s defense of radiation, I found discussions of Communication, of Good Works, of Hazards, and of Fate — probable themes for a medieval morality play, but hardly what one expects from an ultra-modern scientific establishment. As I have explained, I went to LLL with a special agenda, related to my profession and my personal history. What I discovered is that Lawrence Livermore Laboratory has a special agenda too. But it isn’t related to scientific inquiry and rational calculation.

In the nuclear era, with the omnipresent threat of intentional or accidental holocaust, a certain amount of denial is necessary, for if we attend to the nuclear problem with an intensity appropriate to its magnitude, we could attend to nothing else. But just as we must guard against being overwhelmed by it, so too we must be careful of accepting reassurances from irrational sources. The nuclear industry’s often repeated rhetorical question, “Would our scientists and engineers expose themselves and their families tot these materials if they were dangerous?” invites the listener to trust uncritically the rationality of scientists and engineers, and to ignore what is known about the substances themselves. If one looks closely, though, at the thought processes of the scientists and engineers, one learns that, yes, they would expose themselves to extreme dangers, because they have succeeded in building a pretend world where workers stop cancer with paper shields, bosses hypothesize that fluorescent lighting is a stronger carcinogen than plutonium, and danger means whatever you feel like having it mean.

My worry at this point is that the real world will blow up before that pretend world collapses.

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 3 <<