This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Book Review: Overcoming Math Anxiety, by Sheila Tobias

by Katherine Yih

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 1, January/February 1981, p. 14 — 16

Katherine Yih is a graduate student in biology and a free-lance journalist. She is active in Ann Arbor SftP, the New World Agriculture Group (NWAG), and the Farm Labor Organizing Committee.

For people who feel themselves to be failures at math, that they were never meant to understand the stuff in the first place, Sheila Tobias’ book, Overcoming Math Anxiety, should be a revelation and perhaps a challenge. Tobias lets us know unequivocally how widespread math anxiety really is. We see the commonness of even many of the details of the sensation of failure in math class and in other encounters with math. In addition, we are given some ideas of how our individual problems might have arisen and how to solve them, for instance, that using intuition is “fair”, even necessary—professional mathematicians use it far more frequently than we are led to believe in class, where the teacher knows the answers to all the problems already. The book is an important first step toward the elimination of math anxiety at the level of the individual.

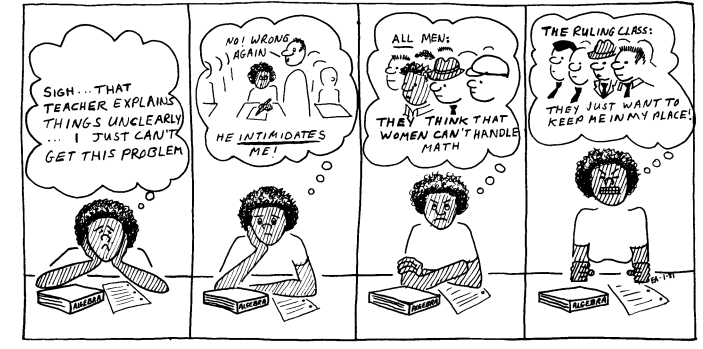

Yet, there are some vital omissions. Notwithstanding the brave talk in the preface— “The book is mainly a discussion of how intimidation, myth, misunderstanding, and missed opportunities have affected a large proportion of the population” (p. 14)–the book settles into more of a psychological analysis of the problem than a political analysis of the institutionalization of math anxiety. It is very clearly recognized that math anxiety is more a problem of women than of men, and the math ability-sex connection is carefully criticized in the chapter on mathematics and sex, but somehow the problem is always personalized in the end: “Feelings are… at the heart of the problem” (p. 15). We are given personal incentives for wanting to get over a fear of math, we are given psychological analyses of how math anxiety operates, and we are given some pointers on how to shake off our individual hang-ups.

One might argue that Tobias was not attempting an exposition of how math anxiety is yet another way male hegemony oppresses women. One might argue, and I would agree, that the book was intended as a guide and support for individuals who, already with an inkling that they were duped into math anxiety, are trying to step past it. But even if one means to approach the issue in that way, to help individuals now, including a political analysis is important. If one sees that one’s fear of math does not simply derive from an eighth-grade teacher who happened to be sexist or racist, but from a whole school system that was sexist or racist, and indeed a whole society that was sexist or racist, I think for some people the urgency to overcome it is heightened—it almost becomes one’s duty to overcome it. (Maybe an analogy can be made with the problem of smoking. Many people, I am sure, have stopped smoking through a realization of its physiological effects and then a lot of hard self-analysis and will. But I also know people who, having tried for years to quit, suddenly succeeded after reading the Mother Jones article detailing how the tobacco industry shapes our desires, profits from our affliction, and maintains our habit through manipulation of legislation. This kind of view is apparently enough to enable some people to leap beyond what have been insurmountable difficulties.)

As mentioned before, Tobias does emphasize math anxiety as largely a problem of women. This is implicit throughout the book and explicit in the chapter, “Mathematics and Sex”, where it is stated, for example, “Both boys and girls are pressured, beginning at age 10, not to excel in areas designated by society as outside their sex-role domain” (p. 78). Yet, in the preface, she is clearly equivocal about how much a feminist issue math anxiety is:

Four years ago, when I began, I hypothesized that mathematics anxiety and mathematics avoidance were feminist issues. Now I am not so sure. Observing men has shown me that some men as well as the majority of women have been denied the pleasures and the power that competence in math and science can provide. The feminists sounded the alarm. But, as a result, people of both sexes are beginning to reassess their mathematical potential. (p. 15-16)

In one passage, criticisms such as those I make are acknowledged:

Several feminists criticize the anxiety model, pointing out that since the causes of math anxiety lie in “political and social forces that oppress women” and are not wholly psychological and educational in origin, the goal of remediation should not be “the curing of an individual case but the elimination of the conditions that foster the disease.” (p. 97)

But the identification of math anxiety as a feminist issue is seen by Tobias as risky.

The identification of mathematics anxiety as a problem for women could become two-edged. Focusing on one more female “disability” may feed the prejudices that already abound in the real world about women and math, women and science, and women and machines. We also have to consider the needs of women who are very competent in math and have a hard time proving this to their colleagues. Finally, we have to contemplate the possibility that attention given to this issue might expose women to exploitation by “math anxiety experts”.(p. 97)

Would Tobias then see affirmative action programs as feeding existing prejedices about women and minorities not belonging in positions of power? Would she see the spread of women’s crisis centers as exposing women to “rape experts”, and therefore undesirable or at best something to be weighed against its supposed disadvantages?

Be this as it may, the sexism issue is at least addressed. In contrast, not the barest mention is made of math anxiety as if affects minorities or the working class in general. In spite of the purposely personal approach taken in the book, it would have gained power by including some degree of discussion of math anxiety as a manifestation of institutionalized sexism and racism in a class society.

Ultimately, a recognition and analysis of math anxiety as a social problem, whose origins, perpetuation, and solution lie in society, is necessary in order for us to begin working on it as such. Case by case rehabilitation alone cannot hope to eradicate social problems.

The book has provoked in me some thoughts about teaching. I think a great deal more attention needs to be given by radicals to the teaching of basic skills at the adult level. It is in basic-skills classrooms that we shall encounter the people oppressed by our educational system who have already determined to do something about it. Possibly they are seeking nothing more than a solution to an individual problem. The duty of a radical teacher is to convert the quest for solutions to personal problems to action for solutions to social problems. This requires three processes, some easier than others.

The first is of course the teaching of the “subject matter” itself. This, no doubt, calls for the usual drills, repetitive exercises, memorization, etc., depending on the material. Such is practice. However, effective teaching for adults should include the following two elements which are often omitted in schools:

First, wherever possible, the process(es) by which one arrives at the solution, acceptable punctuation, etc., should be explained logically and in terms of previously acquired knowledge. When there are several ways to solve a problem, they should be acknowledged, as for example Tobias acknowledges them in the chapter on word-problem solving. When there is no easy logic to explain something, as in the case of some mathematical postulates or spellings, this should be made plain. In other words, real, generalizable learning cannot happen without demystification of the problem-solving process.

The second element to be included is the elimination of individuals’ feelings of special incompetence. Maybe this is best done by confronting the hang-ups in group talks. Tobias places a lot of emphasis on this:

I believe that this talking process is at the heart of the treatment of math anxiety. As we have seen, it helps some people to know that they are not the only ones to suffer from fears of inadequacy about math or science. (p. 248)

She describes the variations on “math therapy” or “math desensitization” used in workshops around the country. The discussion is instructive for teachers of other kinds of skills as well.

The socially important consequence of teaching basic skills in this way is the generation of self-confidence.

The second process in the duty of radical “remedial” teachers is the provocation of the question of how and why one was kept ignorant for so long. This analysis and questioning of external circumstances is essentially analogous to the first stage of consciousness-raising about any issue, and is absolutely prerequisite to useful action. It should be easily worked into group discussions, when it does not arise on its own.

The third process is the making of political consciousness and activism. This is what I conceive of as the second stage of consciousness-raising, the realization of one’s own role in changing external circumstances. Obviously, this is most often a long and tortuous process, and no one person ever really accomplishes it for another. But this must be the goal and inspiration of radical teaching.

Tobias gives both students and teachers much knowledge indispensable to the process of learning (or teaching) mathematical skills. Her own closeness to math anxiety, her travels to various math workshops and clinics across the country, her discussions with practiced teachers, provide us a wealth of accumulated experience.

The book is wanting with regard to raising political consciousness. I do not argue that this was ever its intent, only that it should have been.

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 1 <<